Dragons, phoenixes and basilisks: None of these medieval beasts were ever sighted in Mesoamerican territory. Busy building pyramids and astronomical observatories, the ancient civilizations that populated present-day Mexico knew neither castles nor crusading knights. The question, however, remains: Why was there no Middle Ages in Mexico?

This question is fundamentally misguided for art historian Maira Montenegro, who recently graduated from the Master’s degree in Curatorial Studies at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). Before answering why there was no Middle Ages in Mexico, Montenegro explains that defining what this period was is a good starting point.

“The Middle Ages,” the specialist told Mexico News Daily, “is a historiographical category created to study a historical period in Europe.” Temporally, it is located between the fall of the Eastern Roman Empire and early modernity in Europe. According to the historical magazine Medieval Times, the Middle Ages began in AD 476 and spanned a thousand years.

It was a period of profound theological exploration, translation of Greek philosophical texts and extensive artistic development, especially that related to the religious work of the Christian world. Furthermore, Montenegro adds, “this category [the Middle Ages] can be controversial and open to criticism,” as it depends on the local context in which a given work was created.

Dominated by the construction of magnificent and somber cathedrals, the Middle Ages — or Dark Ages, as the period is also known — was fundamentally influenced by the spread of Christianity. This historical period was characterized by profound religious violence and “great political unrest,” The Medieval Times points out, “which resulted in the founding of many modern European countries.”

Broadly speaking, this extensive historical period — which lasted over 10 centuries —can be divided into two main stages:

- The High Middle Ages, between the 5th and 10th centuries

- The Late Middle Ages, between the 10th and 15th centuries

According to the University of Valencia, the High Middle Ages were characterized “by the struggle for supremacy between the three contemporary empires: the Byzantine, the Islamic and the Carolingian.” In the latter half, known as the Late Middle Ages, the geopolitical arrangements created during the preceding centuries began to decline.

What happened during the Middle Ages in Mexico?

Just as Europe had specific categories for this historical period, Mesoamerica and her cultures had their own. These historical processes had no connection with the European ones. Around the beginning of the Middle Ages, Mesoamerican civilizations were already deep into the Early Classic period, which lasted from around AD 150 to -600).

As archaeologist and anthropoligist George L. Cowgill wrote for Arqueología Mexicana magazine, by then, the ancient civilizations that populated Mesoamerica had already reached a “high level of development,” which was “evident in the complexity of their religious systems, the monumentality of their pyramids and other civic-ceremonial structures [as well as] the refinement of their artistic styles.”

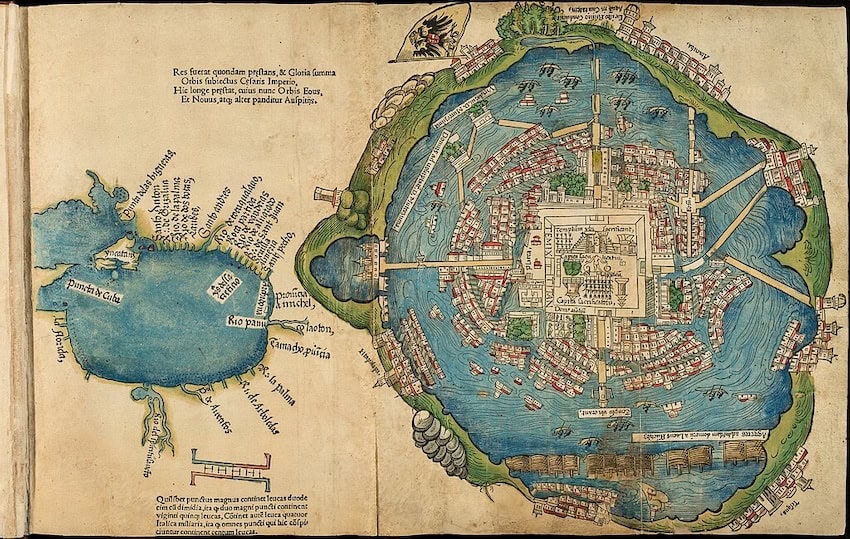

Even in the most arid regions, entire cities had complex irrigation and water supply systems. For example, the sacred city of Teotihuacan, in the Basin of Mexico, and Monte Albán, the jewel of the Valley of Oaxaca, had already reached their architectural peak and were weaving their trade networks through present-day Mexico.

In the Yucatán Peninsula, the Maya had already developed a complex ritual calendar aligned with the stars and celestial cycles. Beyond the allegedly centuries-old cleansing rituals the Riviera offers today, this culture had already developed medical science and technology for dental procedures, as shown by research published by UNAM’s FES Iztacala campus.

Although the Middle Ages never really happened in Mexico, the Spaniards brought some unique medieval souvenirs from Europe. “In the summer of 1520,” as documented by the UNAM’s Institute of Historical Research, “Mexico-Tenochtitlan was gripped by a smallpox epidemic.” The disease wiped out 90% of the original population of what was then Nueva España. Other sources suggest that it was only about half of the native population, which is nonetheless scandalous and grievous.

The consequences were so dire that this spread of the virus is now considered the first pandemic ever recorded in the new world.

Why was there no Middle Ages in Mexico?

Regarding why there was no Middle Ages in Mexico, Montenegro explains that “this is a historiographical category for understanding a European process, in a context with distinct traditions and ethnicities.” The only known “medieval” settlement in the Americas occurred in 1021 AD, after the Vikings arrived on the island of Newfoundland, in what is now Canada. However, the University of Groningen (Norway) confirmed in 2021 that this settlement never truly prospered. Therefore, it is virtually impossible for Norse navigators to ever reach Mexican territory.

Half a century later, when the Spanish invaders arrived in the Americas, the Middle Ages were already coming to an end in Europe. Therefore, the art historian poses a question that seems more interesting to her: Why should Mexico have a Middle Ages? For her, this responds to this constant desire to “fit into European molds,” which seems to “impose a colonial category” on the country’s own historical processes.

Montenegro points out that historians and those dedicated to analyzing these historical processes must adapt these categories to more local issues. In the Mexican context, processes occurred completely unrelated to Europe. Mesoamerican timelines have nothing to do with medieval development on the theological, philosophical or scientific levels. Ultimately, “History should not always be as told by Europe,” the specialist concludes.

Andrea Fischer contributes to the features desk at Mexico News Daily. She has edited and written for National Geographic en Español and Muy Interesante México, and continues to be an advocate for anything that screams science. Or yoga. Or both.