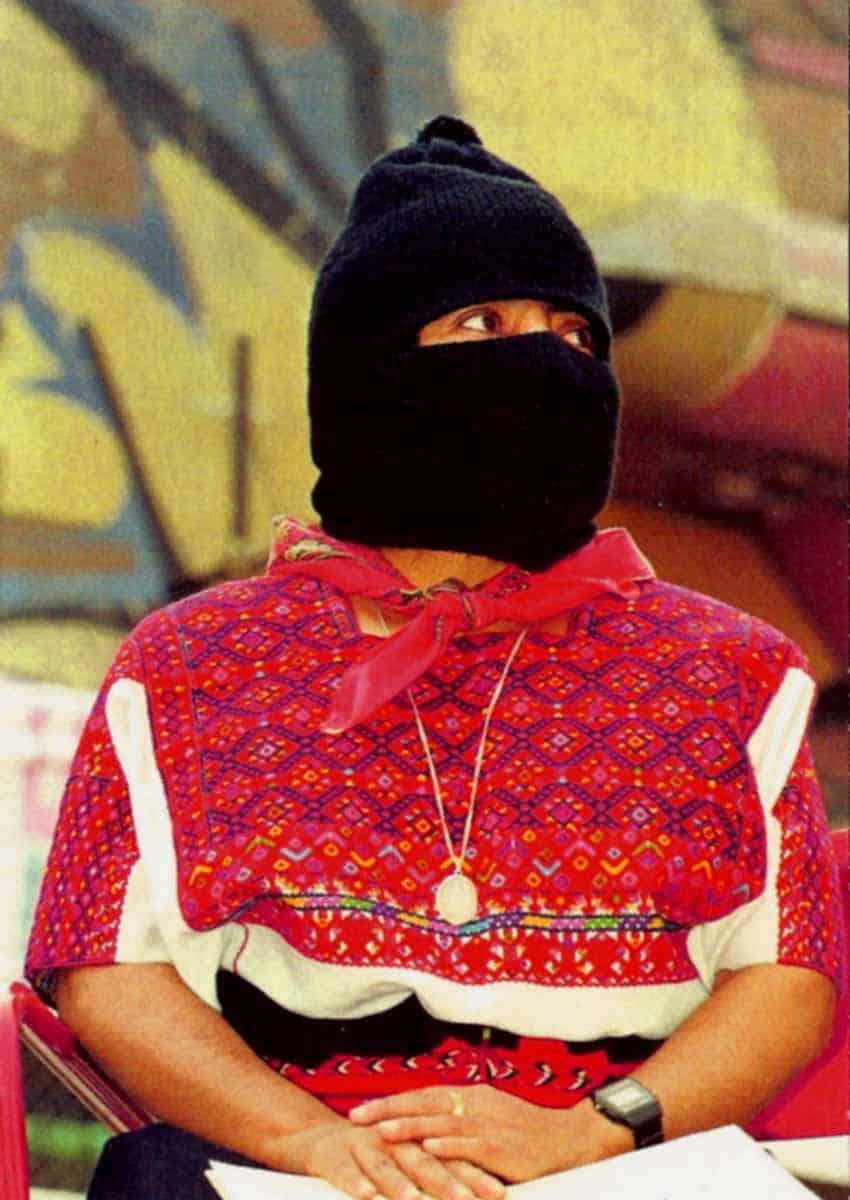

For those of us 50 and older, it seems like yesterday — the masked, charismatic Subcomandante Marcos taking the world by storm to demand justice for a jungle people threatened by globalization and “the new world order.”

He and the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN) made their dramatic appearance on January 1, 1994, the day the North American Free Trade Agreement went into effect. The treaty had been decried by many, but this armed insurgency cut through all that.

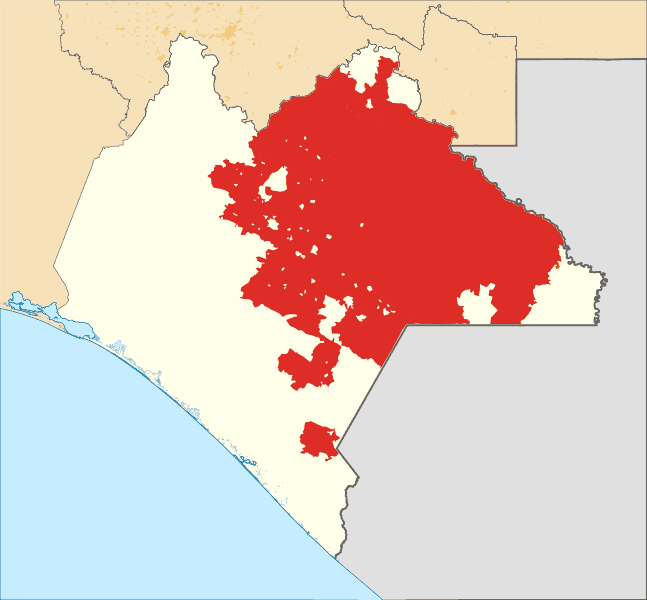

EZLN didn’t just pop up out of nowhere. Chiapas has had a long and sometimes violent history of conflict. The Zapatistas, named after the Mexican Revolution general Emiliano Zapata, organized in 1983 after decades of failure to resolve economic, political and cultural issues.

But they remained obscure until they took over seven towns by force, including San Cristóbal de la Casas, making a declaration there that got Mexico’s and the world’s attention.

Actual fighting with federal forces only lasted two weeks.

The Zapatistas had impeccable timing: the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) had severely weakened (and would officially fall six years later). And instead of limiting their actions to petitioning the Mexican political system, the EZLN reached out internationally via contacts and the Internet.

To people outside Mexico, it made for a great underdog story. And as word spread, foreign journalists flocked to Chiapas, giving them nearly glowing coverage.

This forced the Mexican government to sign the San Andrés Peace Accords in 1996, but it balked in 2001 when the Zapatistas marched to Mexico City to have it formally put into law. Instead, the congress passed a watered-down version, and the Zapatistas broke all talks with them.

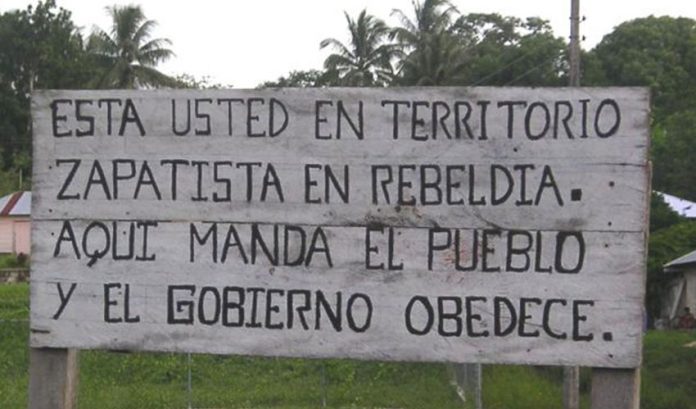

Instead, they focused on creating an “autonomous zone” with the support of certain areas of Chiapas and the international leftist community. Their success with foreign organizations is somewhat unusual and comes not only because EZLN fights for indigenous rights and against capitalism and globalism, but also because their organization is a mix of traditional and modern sensibilities, which inspired organizers to allow women a more visible role in their movement.

However, it is ironic that an anti-globalism movement would have decades-long ties with foreign organizations. It has been vital to their survival. International organizations provide donations and outlets for selling products like coffee in a way they say provides an alternative to globalism that does not abuse native peoples.

The connection to the world outside Mexico has influenced Zapatista priorities, causing them to adopt stances on issues as varied as gender identity, the Ukraine-Russia conflict, COVID policies, rail lines in Norwegian Sami territory and Mexico’s Maya Train project.

The effectiveness of the autonomous strategy locally is debatable. It has meant developing local solutions for needs such as healthcare and education. However, Chiapas, including Zapatista territory, remains extremely impoverished.

Traditional farming practices are not enough to live on, and migration out to other parts of Mexico and to the United States has been significant in the past couple of decades. Illegal logging, especially in the Lacandon Rainforest, has led to severe environmental degradation, says local activist Eric Eberman of the Colibri-Tz’unun Reserve.

The lack of federal troops has made the zone attractive to both human and drug smugglers.

The irony does not stop with the fact of international contacts.

Subcomandante Marcos might have been the best tourism spokesman the state ever had. While some tourism and foreign residents had been in Chiapas prior to 1994, the news coverage brought the curious and the idealistic, not only to experience the native cultures, but with the hope of engaging someone in a black Zapatista balaclava as well.

For a time, there were so many people arriving that this tourism took on the name zapaturismo. As late as 2009, markets were filled with Zapatista-themed merchandise. At this point, it has all but disappeared.

Zapatourism hasn’t completely disappeared, but it is certainly not a matter of driving up to one of the communities to say hello. Some tourism offices in San Cristóbal might give you information about entering Zapatista territory but will tell you that doing so is at your own risk.

There is some indication that some Zapatistas are becoming more open to the idea of visitors again, such as the community of Oventic; however, I would recommend contacting an organization that works with the Zapatistas to find out what may or may not be possible through their contacts.

The memory of the uprising has faded since the movement mostly shuns the press, but tourism continues to grow in Chiapas, especially in San Cristóbal. In the past 30 years or so, the city has transformed from a small, isolated town to a cosmopolitan center welcoming hundreds of thousands of travelers each year. It also hosts a significant and growing number of foreign residents.

The tourism has led to a now fairly large community of resident foreigners. Researcher Gustavo Sánchez Espinosa of the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (CIESAS) calls them “lifestyle migrants.”

These are people with incomes in dollars euros, etc., who come to Chiapas looking for some kind of change in their life. They look to live in an exotic locale, but over time, also look for certain amenities from back home — and businesses spring up to accommodate those needs. Mestizo Mexicans call them “neo-hippies;” local indigenous people call them alemantik or gringotik.

The majority of these settle in and around the historic center because of its majestic colonial architecture. But today, this area is now a jumble of the native and the foreign, with streets filled with European-style cafes, organic merchandise stores with streets filled with indigenous women selling handcrafts and other goods, along with people with huge backpacks and neo-hippie clothes and hair. Such residents separate themselves from other migrants, from places like Central America and other parts of Chiapas, attracted to the city for economic reasons.

In a way, the division revives the original purpose of the historic center, which began as a fort, then became an enclave for the colonial Spanish, with the poor and indigenous on the periphery.

It is highly unlikely that Marcos or any of the other leaders imagined that their stand against the outside world would instead bring the world to their doorstep.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.