The Lerma River originates in the state of Mexico, flows into Lake Chapala and emerges in Jalisco as the Santiago River. The two rivers are among the most polluted in the country, contaminated by so much human and industrial waste that treatment plants are overwhelmed, exposing locals to a toxic environment and a nauseating stench.

Numerous projects have been launched to clean up the Lerma-Santiago river system, but none have succeeded, prompting people living alongside the rivers to seek their own solutions.

Two of these grassroots approaches have stood the test of time. Both are schemes to filter the noxious river water, one employing eggshells and the other volcanic tezontle stones also known as clinkers or scoria.

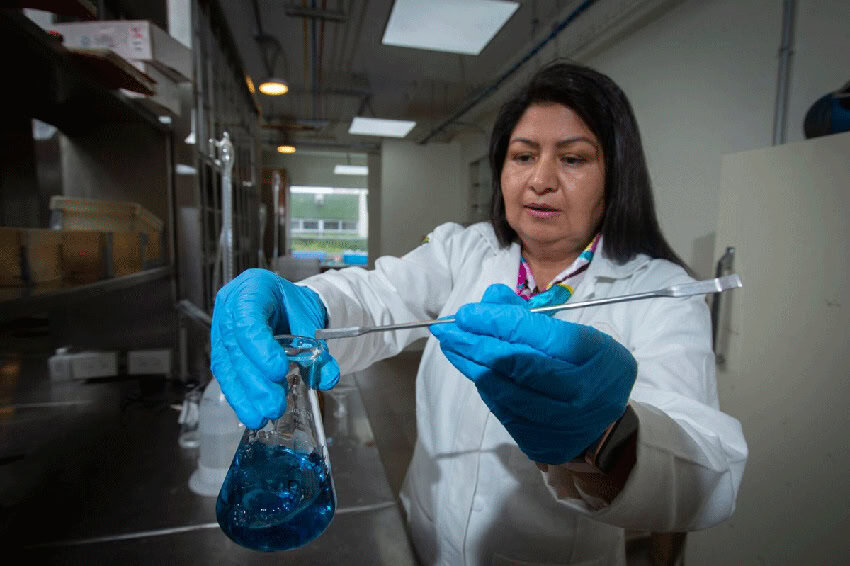

The eggshell movement got its start around 2019 when Lerma resident Elvia Evangelina Árias discovered that her neighbor, a water researcher named Verónica Martínez Miranda, had clean water coming out of her tap. In contrast, Árias’s water was yellow and smelly.

The homemade eggshell filter

Both Árias and Martínez got their water from wells partially contaminated by the Lerma River, but Martínez had protected her well with a homemade filter made of eggshells, lime and magnesium oxide.

Says Árias: “From Dr. Martínez I learned that eggshells — which are made of calcium carbonate — contain countless tiny pores that trap heavy metals and contaminants like nitrogen and phosphorus.”

From this conversation, a plan was formed: to create filters around wells near the Lerma River. The filters would be ditches filled with eggshells, quicklime and magnesium, and the aim would be to transform contaminated wells into sources of clean, drinkable water.

With this in mind, Árias and Martínez formed a civil society organization called H2O Lerma con Encanto which put out a call for eggshells.

The response was widespread and surprising. People all over began to save their eggshells and to take them to collection centers, which forwarded them to H2O Lerma.

Clean water from contaminated wells

“We made 10 protective barriers around 10 wells,” Árias told me. “Our barriers filter out the contaminants from the river. Each well is different and each requires a study. For example, you can add dolomite or iron filings, if needed— it all depends on the contaminants present. The upshot is that all 10 wells are now producing clean, potable water and they will continue to produce it for five to 40 years, depending on how close the well is to the river.”

After demonstrating the effectiveness of their filters near Mexico City and Toluca, plans were made to protect a well near the town of El Salto on the bank of the Santiago River in Jalisco. Hundreds of people contributed eggshells from all over the state.

In August of 2021, however, local authorities intervened, citing legal requirements that had not been met. Practically overnight, the project had to be abandoned in Jalisco.

Five tons of eggshells

In the state of Mexico, however, the donation of eggshells continued unabated and today has reached the point where around five tons are collected every month.

H2O Lerma, however, has started using Martínez’s system for a new purpose: to help wastewater treatment plants do their job better.

“We are creating eggshell biofilters for these plants,” says Árias, “for example, we are helping a treatment plant in the town of Jocotitlán meet its standards. It used to have to pay a fine for not meeting them! Now, thanks to our filters, the plant’s consumption of electricity has been reduced, at times by 50 percent.”

While the use of eggshell filters has been put on hold in Jalisco, a different approach to cleaning contaminated water — using volcanic rock — is presently undergoing testing on the banks of the Santiago at one of its most polluted points, alongside the town of Juanacaxtle.

Toxic water, desperate farmers

“All along the trajectory from Lake Chapala to Guadalajara,” says water researcher Joshua Greene, “there are 2,000 families that have concessions to use the river for irrigation purposes. They are trying to eke out a living by farming, and when the weather gets dry, they have no choice but to irrigate their crops with the malodorous, toxic, river water.”

“They’re using it to grow wheat and oats and hopefully not so much for vegetables. Are they concerned? They certainly are, in fact, they don’t consume the stuff that grows on their own land because they know what they’re putting on it. So they sell it and buy their wheat and oats from somewhere else.”

Clinkers to the rescue

In 2016 Greene helped local people get funding to build the prototype of a simple filtration system that might allow farmers to take the filthy water from the river and transform it into grey water suitable for irrigation purposes.

This filter, known as a constructed wetland, is a channel filled with a cheap, readily available volcanic rock called tezontle in Mexican Spanish and scoria or volcanic clinkers in English. This lightweight rock is full of holes which are home to bacteria that break down human waste.

Reeds and certain flowers are then planted in the bed of wet tezontle to absorb chemicals and heavy metals.

“We set up our system for educational purposes,” says Greene, “to show what might be possible. It measures 4 by 16 meters, but you could make something simpler: just a channel the width of a backhoe would do the trick. It’s on the property of a farmer whose family now happily uses the water that comes from it to grow things like moringa and tobacco and to water a small orchard.”

The pros and cons of using eggshell and tezontle filters to clean dirty water are presently being looked into by the government of President Claudia Sheinbaum. Worried Mexicans living alongside the Lerma, the Santiago and many other polluted rivers are hopeful that the great clean-up of filthy rivers will finally become a reality.

John Pint has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of “A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area” and co-author of “Outdoors in Western Mexico.” More of his writing can be found on his website.