Barbacoa is like a compass pointing out the rich regional variation of Mexican gastronomy. When its needle points north, this slow-cooked weekend specialty likely features beef; to the east, it’s made with pork; to the west with either goat or beef; and to the south in myriad ways.

However, the most famous version comes from the state of Hidalgo in Mexico’s heartland, where it’s made from lamb in places like Actopan, Tulancingo, Atotonilco el Grande, Ixmiquilpan and Villa de Tezontepec. Here, lamb is wrapped in maguey leaves and pit-cooked overnight until incredibly tender, with the meat typically shredded for tacos with salsa borracha and the drippings caught in a pot and used to make consomé.

The birth of barbacoa in Mexico

The birth of barbacoa is often linked to the history of barbecue, which began with the Indigenous Taino people in the Caribbean, who as the story goes, invented the technique of slow-cooking meat in a pit. The meat was placed on a wood frame over the fire, a method they termed barabicu — the origin of what became barbacoa in Mexico and barbecue in the United States.

Of course, there is an alternative theory that puts the origins of pit cooking in Mexico with the Maya pib. This could have come about via Caribbean influences but also may have developed independently. People have been using earth ovens for tens of thousands of years in culinary traditions that span the globe.

Thus, some believe that barbacoa sprung not from the Taino barabicu but from the Maya Baalbak’Kaab, a pre-Columbian tradition of pib-cooked meat that began on the Yucatán peninsula with gamey proteins like turkey, deer and rabbit.

Evolution of the dish in the 19th century

The written history of barbacoa dates to the 18th century, with the 1831 cookbook “El cocinero mexicano” already noting a handful of variations, including African, Mexican, mountain barbacoa and a style reserved for small animals. Notably, all of the extant styles at this point utilized the horno de tierra, or earth oven.

Beef was the star of the memorable barbacoa served after a bullfight described in Frances Calderón de la Barca’s pioneering 19th-century travelogue “Life in Mexico,” published in 1843.

“The animal, when dead,” wrote the Scottish-born wife of Spain’s first ambassador to independent Mexico, “was given as a present to the toreadores; and this bull, cut in pieces, they bury with his skin on, in a hole in the ground previously prepared with fire in it, which is then covered over with earth and branches. During a certain time, it remains baking in this natural oven, and the common people consider it a great delicacy.”

How barbacoa is prepared in Hidalgo

The evolution of a regionally distinct style, barbacoa hidalguense, can be traced from this era. As early as 1844, barbacoa was noted as most commonly served in Hidalgo cities such as Actopan and Apan. It was particularly popular for occasions like weddings. The association with special events continued into the 20th century— although for contemporary Hidalgo barbacoa, every weekend qualifies as a special occasion, since the dish is commonly served in homes, restaurants and roadside stands across the state on Saturdays and Sundays.

Voices of Mexico, an English-language magazine at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), describing the traditional flavors of Hidalgo, details barbacoa’s preparation in traditional hoyos, the three-feet-deep pits built to cook the dish:

“The homemade variety takes a long time to prepare, beginning the day before when the animal is slaughtered, drained of blood and cut into pieces… The hole is usually dug in the patio of the house, where thick logs are placed, making a little vault. Inside it are placed twigs to get the fire going, and on top of that, stones, to absorb all the heat.

“After several hours when the stones are red hot, a recipient is put on top of them containing vegetables, rice and guajillo chili peppers, where the meat drippings fall, to make the famous consomé. Over the recipient the cooks put a grill made of mesquite branches or metal, then a layer of maguey leaves, the salted seasoned meat, and a last layer of more leaves, to give the meat its characteristic flavor. Finally, the oven is covered over with dirt, and the meat is left to cook for between six and twelve hours, depending on the amount of meat.”

Tacos and the iconic salsa borracha

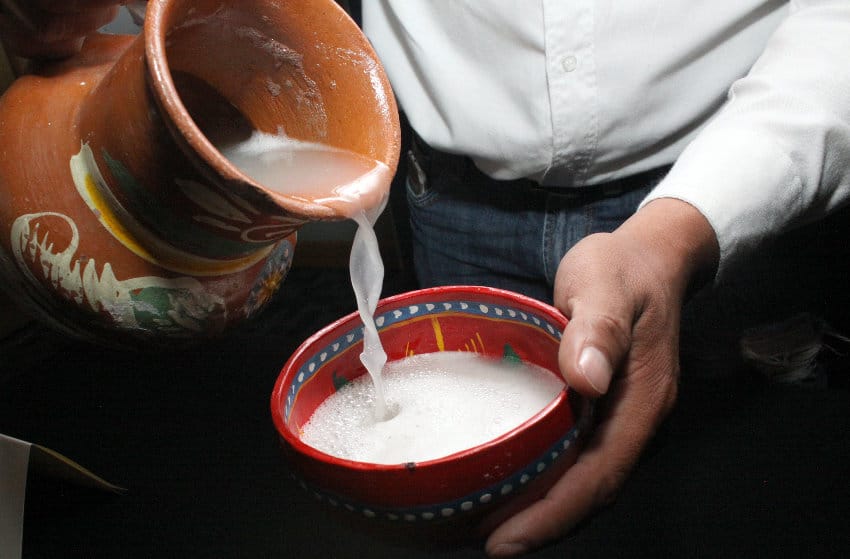

Hidalgo-style barbacoa is not just noted for its pit-cooked lamb but also for the blue corn tortillas in which tacos are wrapped and the iconic “drunken” sauce that so frequently accompanies them: salsa borracha. Made from ground pasilla chiles, garlic, olive oil and potent pulque, it’s a spicy accompaniment to the tender lamb and complements traditional taco toppings like onion and cilantro.

Barbacoa festivals in Hidalgo and the rise of ximbo

The annual Feria de la Barbacoa in historic Actopan is considered the premier showcase for this regional specialty, drawing over 100,000 visitors during its 10-day run each July. In addition to competing barbacoa from regional pitmasters, the feria also offers opportunities to sample another Actopan favorite: ximbo.

There are several similarities in how barbacoa and ximbo are made, including slow cooking in the same ovens. However, when ximbo originated in the 1980s, it was made with chicken, not pork or lamb— which are valid meat options for the dish today. Hence, its original name: pollo en penca, with penca referring to the maguey leaves in which the dish, like barbacoa, is wrapped.

The dish is generally served with sides like nopales and cueritos (pickled pork rinds), acquiring its name in the Indigenous Otomi language, ximbo, during the 1990s as it evolved into one of the most recent additions to Hidalgo’s acclaimed gastronomy. The Otomi are the traditional inhabitants of the Mezquital Valley within which Actopan and many of Hidalgo’s other barbacoa havens are located.

The ancestral home of pulque

Pulque, the alcoholic beverage made from fermented agave sap, has been made in central Mexico since the earliest history of Mesoamerica. Hidalgo remains the top national producer, accounting for over 78% of all pulque made in Mexico as recently as 2020. Though there aren’t nearly as many pulquerías as there used to be, these traditional taverns still exist for those who’d like to try pulque in something other than salsa borracha.

Chris Sands is the Cabo San Lucas local expert for the USA Today travel website 10 Best, writer of Fodor’s Los Cabos travel guidebook and a contributor to numerous websites and publications, including Tasting Table, Marriott Bonvoy Traveler, Forbes Travel Guide, Porthole Cruise, Cabo Living and Mexico News Daily. His specialty is travel-related content and lifestyle features focused on food, wine and golf.