Why is it hard to get real vanilla in Mexico?

On my first visit to Papantla, in the north of Veracruz, I saw vanilla everywhere – plants, beans, extracts and more besides. Back in Mexico City, I was surprised that it was nearly impossible to find, even in pastry supply businesses. This situation has not improved all that much in 20 years.

So why is it so much harder to find real vanilla, especially compared to some of Mexico’s other delicacies like chocolate, avocados and chapulines (grasshoppers)?

Perhaps the reason is that it is “plain ol’ vanilla,” an ingredient in so many things, but hardly any preparation that absolutely defines it as “Mexican.”

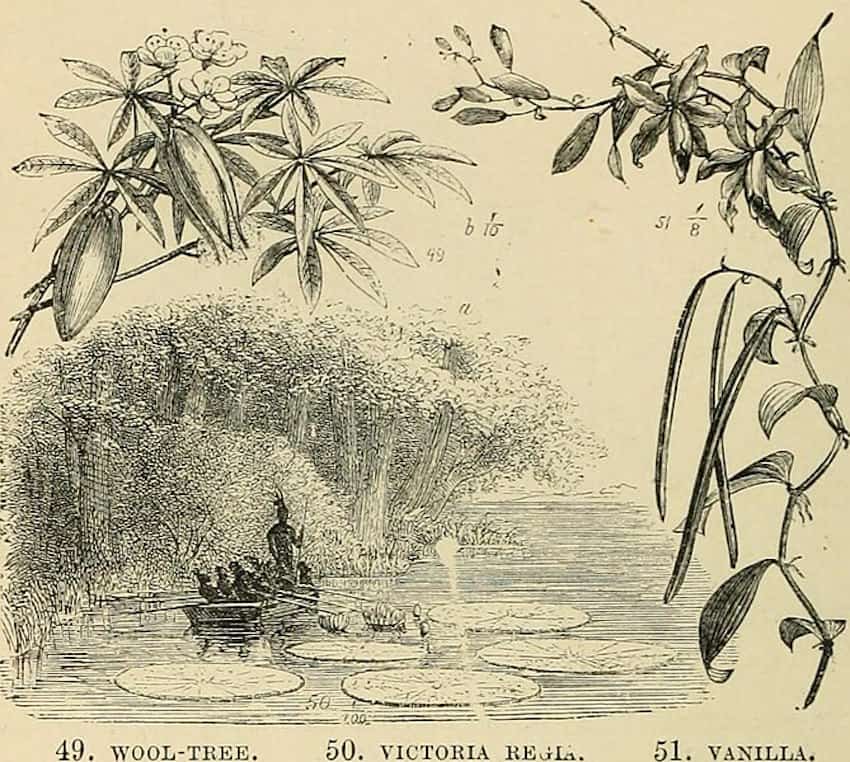

This is curious because the history of vanilla parallels that of world-famous chocolate. First cultivated by the Totonacs of northern Veracruz, the Mexica quickly adopted it after they conquered the region in 1427, considering it a “food of the gods” (and of emperors, of course).

The Spanish enthusiastically adopted it; in fact, they did not drink chocolate without sugar and vanilla. Shipped to Europe, vanilla was quickly favored in sweet dishes.

For three centuries afterwards, Mexico was the only producer of vanilla. The French were the first to try to cultivate it elsewhere, but the plant would not produce the needed pods because its natural pollinator, the melipona bee, exists only in Mexico.

Development of hand-pollination techniques took away Mexico’s monopoly on vanilla cultivation, but it did not make vanilla either cheap or ubiquitous as it is time-consuming and labor-intensive to grow and process.

There is only a short window for successful pollination and a mature pod takes 9 months to cultivate. The pods then need to be parboiled, sweated, dried and left to cure on strict timetables, and much can go wrong during the arduous process. In the end, only 2% of each successfully processed pod has the required essence, which is extracted through a solution of ethanol and water.

This extract contains all of the vanilla’s complex flavor profile, making it prized internationally – so much so that it is not possible to produce enough for the world’s demand. Artificial vanilla (sometimes called vanilla essence) was developed to fill the gap, and is able to reproduce vanilla’s qualities sufficiently for many commercial baked goods. This is the kind of vanilla you are likely to find in a supermarket in Mexico. However, if you really want to appreciate the difference, try a commercial vanilla ice cream side-by-side with a gourmet one, flavored with the real thing.

Because it is often a flavor enhancer rather than the star (like chocolate), most vanilla used in the world is artificial.

But appreciation of what real vanilla can do is growing internationally, keeping demand so high that most Mexican vanilla is exported. This demand, along with Mexico’s famous cost-consciousness, keeps it out of most brick-and-mortar retail venues, even those selling gourmet foods and specialty foods from Mexico.

International interest now extends into the different varieties of vanilla that Mexico can produce as well as those produced by different growing conditions. Although it is grown in six states, only the vanilla cultivated in its native region of northern Veracruz into Puebla can be called “Papantla vanilla.” And the designation does indeed affect the price.

The value of the global vanilla market is expected to hit US $43 billion by 2025, but Mexico ranks only third in production – behind Indonesia and top dog Madagascar – which produces a whopping 43.9% of the world’s supply. Mexico struggles to keep up in part because most vanilla-suitable lands are owned in small plots, thanks to land redistribution efforts in the 20th century.

Mexico produces only 7.8% of the world’s supply but with even green pods fetching up to 1,000 pesos per kilo, there should be plenty of opportunity for Mexican farmers.

To maximize these opportunities, small farmers need to organize and work with marketers to promote the identity of Mexican vanilla in its own right. One such organization is the Mexican Vanilla Plantation, a collective of small growers in the Tuxpan region of Veracruz. They exist not only to support better growing practices but also to help with the complexities of processing and international marketing. The group has even branched into retail foodstuffs that contain their vanilla, like dulce de leche, ice cream, liqueurs and much more. As their English-language name implies, their focus is on export with partners like the Culinary Collective, but they also work with domestic retailers like Palacio de Hierro.

Despite it being more difficult, Oscar Mora Domínguez’s family-owned Xanathlitl is concentrated entirely on the domestic market. Like the Tuxpan collective, he also sees far better value in selling gourmet food products that contain Veracruz vanilla, rather than the pods or the extract. His lines include marmalades, sweet liqueurs and a vanilla-infused coffee. The company does not yet have an online presence, but can be contacted by email or on WhatsApp (228 816 4443).

Best known for its management of the Edward James surrealist gardens in Xilitla, the Pedro y Elena Hernández Foundation began efforts to organize and support vanilla farmers in the Sierra de Otontepec mountains in 2016, in no small part because the family is from northern Veracruz. They leverage the family’s extensive international business experience to provide better materials and technical help to over 160 small farms in various states of development. Forty of them now are able to grow, process and even market their product, avoiding middlemen and getting more benefits from their crops.

With all this promise, there is unfortunately one other problem that keeps the future of vanilla in Mexico in doubt. Like avocados and blue agave, the potential for high profits make farmers vulnerable to organized crime. The problem of robbery and extortion rises when vanilla prices do, says Juan Carlos Guzmán of the Chapingo Autonomous University, Mexico’s premier agricultural school.

Today you can sometimes get lucky and find the real thing in boutique stores and farmers markets in places like San Miguel de Allende. But perhaps the biggest break for those of us who want the real thing from its land of origin is the growth of food shopping via the Internet. Whereas I was stumped 20 years ago as to where to buy it outside of Papantla, a Google search now often provides the answer.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico over 20 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.