Life in many parts of Mexico City revolves around green space. Chapultepec Park, nearly twice the size of Manhattan’s Central Park, is said to average 40,000 visitors per day. The Alameda Central, situated next to the Palacio de Bellas Artes in the Historic Center, may just be the oldest park in the Americas. Desierto de los Leones National Park is one of the most popular destinations for urbanites to go hiking. Still, none of these parks quite match the energy of a Sunday morning stroll through Condesa’s leafy, lovely Parque México.

By 9 a.m., locals have already claimed their spots: joggers speed down the winding pathways, dog owners gossip while their pets play off-leash and families spread blankets on patches of grass to enjoy a weekend picnic.

The sensory experience in Parque México is distinctly Mexico City. While vendors selling fresh fruit and tamales call out their offerings, the scent of coffee drifts from the plethora of cafes that line the streets. Music from an impromptu dance class will echo from the Art Deco amphitheater while children shriek with delight by the duck pond.

This 88,000-square-meter urban sanctuary doesn’t just provide respite from the surrounding concrete; Parque México tells a unique side of the story of Mexico City’s evolution through its architecture, activities and the diverse crowd it attracts every weekend.

Its origins are colonial

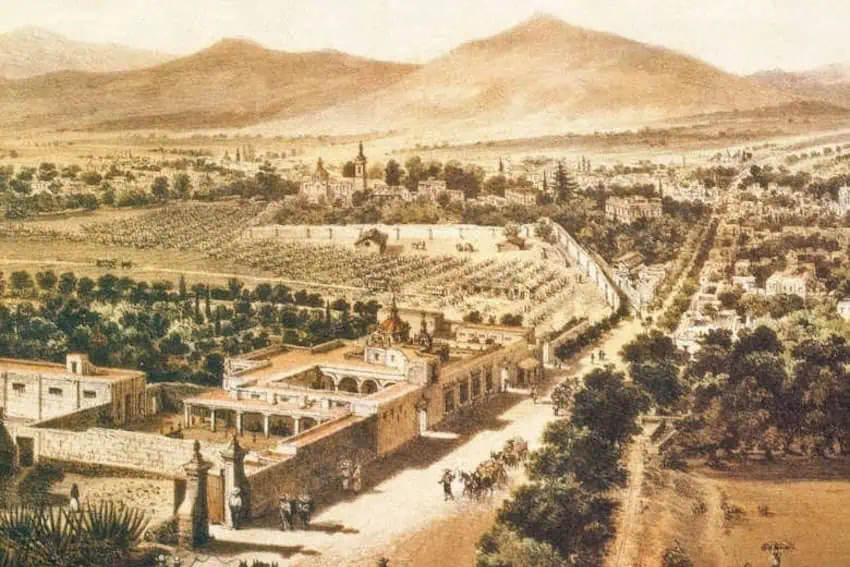

Parque México’s history stretches further back than many visitors realize. The land was originally part of the Santa Catalina del Arenal hacienda, built in 1610. Then on the outskirts of Mexico City and spanning much of what is now Condesa, it was primarily dedicated to pulque production, livestock and fruit cultivation. Over the centuries, the hacienda changed hands several times. By the 1700s, it fell under the ownership of the Third Countess of Miravalle, who was a descendant of Moctezuma and related to Charles II of Spain.

It was once a racetrack

In the early 20th century, the Jockey Club purchased a portion of this land and built a horse racing track, which explains the park’s oval shape. By the end of the Mexican Revolution, the route where horses once galloped for the entertainment of Mexico City’s elite ceased operations. The developers who bought the former racetrack in 1927 were bound by a contract stipulating that 60,000 square meters of the property must be converted into a public park, and Parque México was born.

That’s not its name

Even though everyone calls it Parque México, that’s not actually the park’s official name. It’s technically called Parque General San Martín, named after José de San Martín, an independence leader in Argentina, Chile and Peru. The dedication was officially made in December 1927 as a gesture of goodwill towards Argentina. Nonetheless, the park is commonly known and referred to as Parque México due to its location on Avenida México. Need a visual? Head to the northwest corner of the park near the Amalia Gonzalez Library, where a bust of San Martín stands proud.

Its layout was inspired by a British urban planner

José Luis Cuevas Pietrasanta, the visionary architect behind the Hipódromo Condesa neighborhood, was heavily inspired by British urban planner Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City movement.

Howard pioneered the innovative city development concept with the aim of creating urban environments that were both sustainable and peaceful, combining the best aspects of city life and nature. Cuevas Pietrasanta used these principles when planning Parque México, resulting in the capital’s most progressive and successful urban development project of the 1920s. As most of the city expanded haphazardly, Hipódromo Condesa emerged as a blueprint for future use. It was the first Mexico City neighborhood where buildings and nature were deliberately planned to coexist harmoniously, with the streets surrounding Parque México growing outward in a circular, whimsical fashion.

It took three architects

More than just the park’s chief architect, José Luis Cuevas Pietrasanta was one of Mexico City’s most influential urban designers. Beyond Colonia Hipódromo, he designed the upscale Lomas de Chapultepec neighborhood, the Casa de José Gargollo y Garay on Paseo de la Reforma and the Edison Building in the Historic Center.

Leonardo Noriega had a knack for Art Deco, which he used when designing the striking Foro Lindbergh amphitheater. Its geometric forms, decorative motifs and clean lines are a testament to his artistic flair. Even though Noriega’s name isn’t as prominent of his contemporaries, his contribution to Parque México was profound and helped establish Art Deco as a defining style in Mexico City’s architectural identity.

Is a park without a sculpture really a park? According to José María Fernández Urbina, the answer is no. Fernández Urbina brought his three-dimensional expertise to the Parque México project, creating the famous Fuente de los Cántaros (Fountain of the Jugs) that remains one of the park’s most beloved features.

Together, these three designers didn’t only create a beautiful green space in the heat of Condesa. By blending European influences with Mexican aesthetics, the team introduced a bold cultural statement about modern Mexican identity during the period of national reinvention that followed the Mexican Revolution.

Charles Lindbergh was here… maybe

The Art Deco Foro Lindbergh amphitheater serves as Parque México’s architectural centrepiece, the cultural heart and preferred meeting point for salsa fanatics. But many visitors remain unaware of the fascinating story behind its name.

The forum is indeed named after Charles Lindbergh, the American aviator who flew the first solo nonstop transatlantic flight from New York to Paris. Some say his accomplishment captured the imagination of Mexico City’s urban planners.

Local legend says something more dramatic. Some believe that Lindbergh himself landed an airplane in this very location in December 1927. While historians debate whether this actually occurred, the story speaks to Mexico’s enthusiasm for aviation advancements during this era, perhaps as a way to shrink distances between nations and inspire new international relationships.

It has historic rules

There are several quirky Art Deco-style stone signs throughout the park, all dating to 1927, indicating the proper way to act while visiting to ensure Parque México remains well-maintained. These signs use distinctive language that not only reflects past social norms in Mexico but also showcases how speech used to indicate one’s social class. This feature adds character to Parque México, serving as both a practical guide and a cultural artifact. Look out for signs that say things like “Respect for trees, plants, and grass: is an unequivocal sign of culture” and “Dogs seriously damage a park: bring them leashed.”

It’s a living ecosystem in the middle of the city

Parque México functions as an urban forest within Mexico City. The park’s canopy includes majestic jacarandas, ash trees, palms, firs and native ahuehuetes (Montezuma cypresses), many of which have been present for centuries.

More than just a pretty face, Parque México plays a vital environmental role by helping filter air pollution, reduce urban heat, and provide habitat for wildlife. For residents of the surrounding high-density neighborhoods, the park offers essential access to nature without leaving the city, a living reminder of Mexico’s natural heritage amid the urban landscape.

A bustling cultural hub

Each weekend, over 10,000 visitors transform Parque México into a vibrant social hub. Locals come here for free salsa classes, zumba sessions, and impromptu performances. You can learn to roller skate or how to properly wield an LED saber. If your idea of burning calories on a Sunday is through shopping, vendors fill the park with all sorts of delightful products — artisanal jewelry, house plants, home decor — you can even adopt a cat!

An important historical landmark

Recognized by the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) as a cultural landmark, the park physically represents Mexico City’s urban evolution. A 2008 renovation introduced sustainable irrigation systems to maintain its greenery amid the city’s water challenges.

As Condesa continues to grow into one of the country’s most desirable neighborhoods, Parque México remains an anchor of public accessibility for all to enjoy. The park is open daily, including holidays.

Bethany Platanella is a travel planner and lifestyle writer based in Mexico City. She lives for the dopamine hit that comes directly after booking a plane ticket, exploring local markets, practicing yoga and munching on fresh tortillas. Sign up to receive her Sunday Love Letters to your inbox, peruse her blog, or follow her on Instagram.