The border looms large for all Mexicans who live near it whether or not they cross, says artist Alejandra Phelts, simply because there is a concept of “another side.”

“They say that we in the north are agringado (gringofied) … that we are a mix — a mezcla … We are, but we also have many ‘national’ [Mexican] values that are more strongly seen because we contrast ourselves with ‘the other.’”

Phelts’ work reflects this by being both strongly international and Mexican at the same time.

The movement of peoples nationally and internationally defines the north, especially Baja California. Phelts, born in 1978 in Mexicali, the youngest of five girls, is an example of this: her father migrated to the city when he was very young, eventually founding a university-level school there; her mother came later from Sonora.

Art was in the cards for young Alejandra — her parents met in an art history class and as she grew up the house was filled with books about the subject — but it took time to find her passion. Her first creative endeavor was singing classical music in churches and at events.

She blames the lack of art education in Mexicali for her not thinking about the visual arts at an earlier age.

When she was 17, she decided she wanted to leave Baja and see something of the world. Her family has European heritage, including an aunt who speaks French and encouraged her to study the language.

Studying in France became the logical choice, and she attended the Institut Privé de Philosophie et Théologie Saint Jean in 1998. Here, she had more exposure to the visual arts, going to museums to see classic works and meeting a sculptor who lived in her building.

Phelts says now that her purpose in going to France was not to see the world but rather to find out something about herself.

Upon returning to Mexicali, she still did not dive right into making art. The city had a new art education program, allowing her to get a credential in teaching all kinds of arts to children. Older and able to travel regularly to Tijuana, she gravitated to the Centro Cultural Universitario de Tijuana (CECUT), the region’s main arts center.

She first went to check out the classical music but wound up in the workshop of artist and teacher Alvaro Blancarde, a major figure in promoting the visual arts in Baja. It was the first time she saw a professional artist’s studio in her home state.

Both it and the man impressed her. He was also impressed with her, stating unequivocally that while teaching art is noble, she needed to be producing as well.

Since 2001, Phelts has worked in installation, photography, painting, drawing and more. Her first exhibition was in Tijuana, and then came an opportunity to create a mural at the University of California in San Diego, boosting her confidence.

Since then, her work has been exhibited in various parts of Mexico, the United States, China, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Peru, the Middle East, France and Canada. She was invited to present at TEDx Tijuana in 2013, and in 2016 she represented Mexico as a cultural attaché during a meeting of the G20.

Her creative output focuses on human relationships to the environment and each other. Much is related to her family life — both while growing up and as the mother of two today.

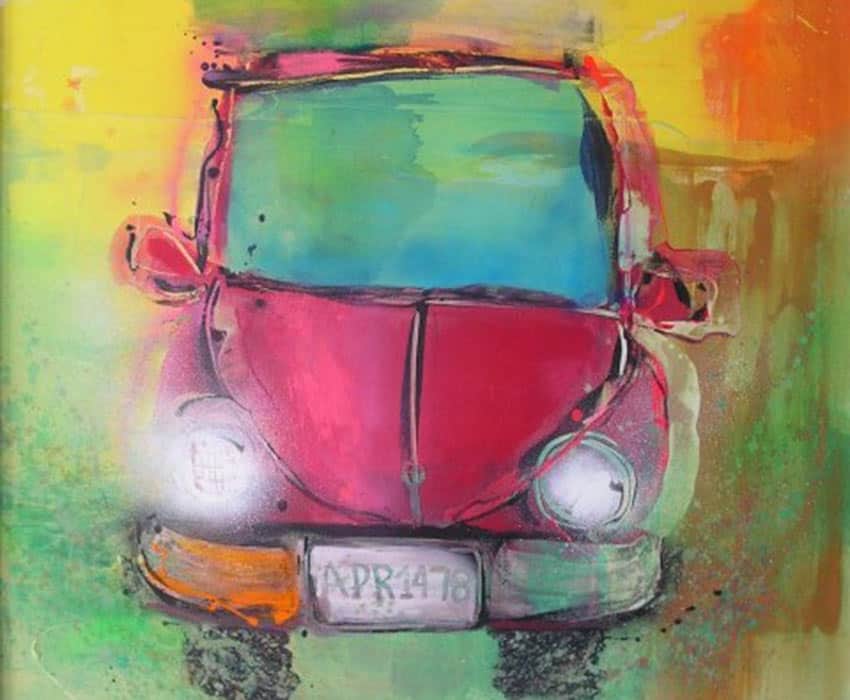

Her work now focuses on the human body (and its accoutrements), but even an early series on automobiles had a family link inspired by vehicles she and her mother owned and how they interacted with others on the road.

Two of her series illustrate Phelts’ worldview best: Costura (Sewing) is a tribute to her upbringing. She calls her mother, Susana Ramos, who taught all her five daughters to sew, “an artist with fabric and a sewing machine.”

“I grew up in a world of color and forms without realizing it,” said Phelts. The clothing in the series reflects her heritage and experience in Europe, but the colors reflect the cross-border world of Baja California.

The series Retratos Iluminados (Illuminated Portraits) continues to examine the feminine but with more emphasis on faces and body language than in Costuras.

Both series are deeply personal, nostalgic and interested in the female experience. But they are also a strong reflection of the mixed and ever-changing world in which Phelts lives. Neither series looks “Mexican” at first glance until you look at them as a continuation of the work of Mexican artists like Frida Kahlo, Remedio Varo and María Izquierdo, who in various ways looked at the world around them and their role in it as women.

Phelts’ work continues examining what it means to be a woman in Mexico, but with a cross-cultural twist.

Today, she lives and works in a Tijuana suburb only four blocks from the ocean. It is curious to see an internationally recognized Mexican artist continue in the northwest of the country, but Tijuana offers pros as well as cons.

A benefit is that she has ready access to the U.S. art market, especially that in southern California, and does a lot of her business in English. A downside is that the local art market is weak and that Mexico’s art world is centered almost entirely on Mexico City.

Although Phelts cannot guarantee that she will always live here, she says that “Tijuana is a very, very interesting place.”

“As an artist, it offers you a kind of movement that an artistic sense needs to create.”

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.