Anyone in the city of Guadalajara with a hummingbird feeder, has probably noticed that any nectar left over at the end of the day inevitably vanishes in the course of the night. This is due to the nocturnal visits of thousands of tequila bats, so named by none other than Sir David Attenborough himself.

These are the bats that normally pollinate the blue agave and if it weren’t for them, the town of Tequila would probably be far more famous for its majestic volcano than for its liquor.

As cave explorers, my friends and I naturally asked ourselves where all those bats must sleep during the daytime and that question led us — years ago — to a very curious river cave located only 22 kilometers from the edge of the city.

It all began in the plaza of a charming pueblito. It was the middle of May, the hottest month of the year in these parts, and the square was already shimmering with heat, although it couldn’t have been earlier than 10:00am. We approached the stooped form of a man relaxing on the only shaded bench around. Tired eyes watched us from a face that sported a harvest of wrinkles, perhaps from years of toil in the burning sun.

“Good morning, caballero, we´ve come here looking for caves in this area. Could you help us?” This was my favorite technique — not very scientific, I’m afraid — for finding caves in Mexico.

The ancient eyes grew puzzled. “¡Ay! If it’s caves you’re looking for, you shouldn’t come to me. Why don’t you ask one of the old men around here?”

Though we were unable to find anyone older than our venerable informant, our question had been overheard by a gentleman — young and friendly — who claimed there was a cave on the ranch that he managed. He was even kind enough to draw us a map to the place, which resulted in our standing knee deep in a muddy swamp about 45 minutes later, trying to find a river, which would lead us to a waterfall which was close to the cave.

While slogging through the muck, little did we suspect that our caving club, Grupo Zotz, was about to encounter one of its greatest challenges.

Eventually we reached the end of the swamp and what did we find but the very river our informant had told us about. So we began following it downstream and after a while came to the top of a quite good-looking waterfall. Impressed by the accuracy of the friendly rancher’s information, all we had to do was find the cave.

Well, that problem was resolved, in a sense, the moment we reached the very edge of the cascade, a strikingly beautiful one at that, with a special plus for cavers. Standing at this spot, vapors rising from the canyon some 20 meters below us reached our noses and we gasped because, in spite of the sunshine and open air, we couldn’t miss the unmistakable, pungent odor of bat guano!

“There really is a cave here,” we said. “All we have to do is find a way down to the base of the waterfall.”

As we had brought no rope, that job took several hours, following a circular route which brought us to the river at a point downstream. Then we had to wend our way through a bamboo jungle to get back to the waterfall. When we finally reached it, we could see a big black hole to the right of the falls and we discovered that our cave entrance was completely flooded. Naturally we made an attempt to “chimney” above the water level and naturally we fell into the drink and this is how Cold Dunk Cave (El Chapuzón) got its name.

This is the closest cave to Guadalajara and one of the most interesting — as well as unusual — caves I have ever been in. It took us a full year to discover that the cave has 623 meters of passages on two different levels, with a small underground river running through most of it. We also learned that Chapuzón Cave has seven entrances, most of them much easier — and drier — than the waterfall entrance.

In the course of mapping the cave, we followed the river to the edge of a small drop. Just below us was a kind of pit filled to the brim with a disgusting mixture of bat guano, bat urine and cave water, with a dead rat floating on top for good measure. Hugging the walls on either side of what we soon christened La Pila de la Pestilencia, we tried our very best to bypass this unsavory soup, but we could find no way to do it. “We’re just going to have to jump in and swim across,” we decided, “but we’ll come back with clothes fit for the occasion.”

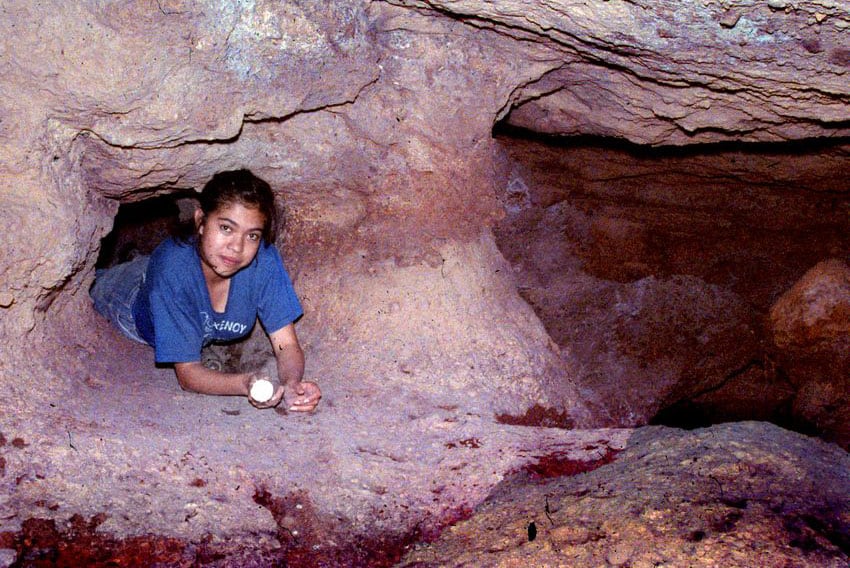

The following week we returned wearing what would best be described as rags. We jumped into the murky black liquid and after a few seconds climbed out of the pool into a long narrow passage whose ceiling and walls were covered by thousands of Leptonycteris bats. Naturally, a population like that was producing great amounts of guano which had resulted in a gooey layer of muck on the floor, at least a foot thick, which sucked at our boots as we tried to walk through it.

To make matters worse, flitting around our head were little bugs we immediately nicknamed “eyeball biters.” These seemed dedicated to making it as difficult as possible to read the compass or take notes for our survey. But we now had a pretty good idea where Guadalajara’s tequila bats were hanging out.

The murciélagos in Cold Dunk Cave seemed to be doing very well for themselves, unlike many Mexican bats which which are literally under attack from all sides.

[soliloquy id="97155"]

Amazingly, the war against bats in this country is based on a case of mistaken identity. Rancheros watch their horses and cattle die a horrible death from paralytic rabies and swear revenge on the vampire bats responsible. When they eventually come upon a cave, they automatically assume that all those bats inside are vampires. Often — as is the case with La Cueva del Chapuzón — the cave is mainly populated by thousands of harmless bats which eat tons of mosquitoes or pollinate many plants whose flowers only open at night.

Among all these friendly bats there may be only a handful of blood-drinking vampires, but the local people typically start fires inside the cave, dynamite it, or seal the entrances with chicken wire, effectively killing off or driving away thousands of innocent and very beneficial creatures.

Fortunately, many people who feed hummingbirds are happy to let bats finish off the daily supply of nectar. If you are among them, be sure to remove the “anti-bee” inserts at night so the bats can reach the nectar during their split-second visits to one of the feeder’s “flowers.”

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.