Many years ago, I taught English in Querétaro, which was then so small you could easily reach every part of it on foot. The first time I crossed the town at dawn, it was dead quiet and I expected to see nothing but empty streets.

To my surprise, I found neither the streets nor the sidewalks empty. It was, in fact, downright dangerous to walk around at that hour because, without warning, gallons of water (clean, fortunately) might come sailing out of any doorway at any time.

This was my first introduction to a curious and charming Mexican custom which, for lack of a better name, I will call the Spotless Sidewalk Syndrome.

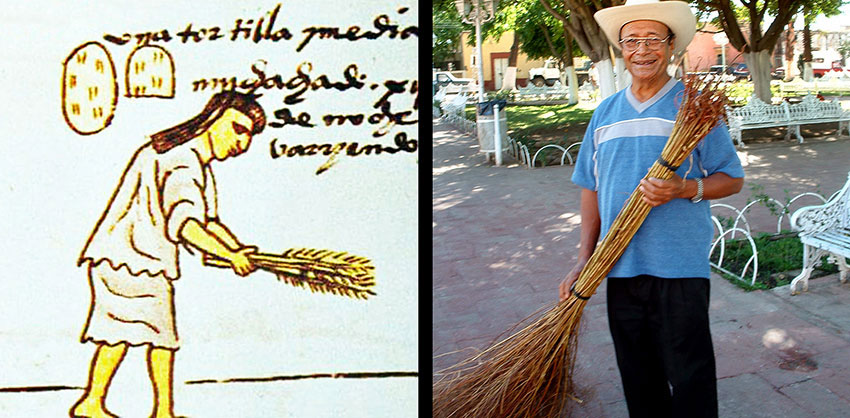

In front of every residence, some energetic individual would be scrubbing or sweeping not only the sidewalk but often a section of the street as well and when they were all finished, there was not a bit of dirt — not even a speck of dust, I swear — on any sidewalk in town, and the streets, too, were impeccably clean.

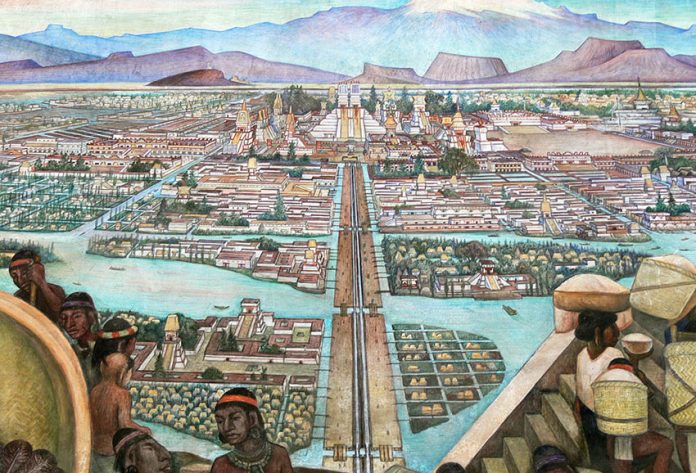

This custom, it seems, goes a long way back in Mexico. It is said that the streets of Tenochtitlán were swept and washed daily by a crew of a thousand street cleaners, who were supervised by health officers and inspectors. While the Aztecs bathed at least once a day, the conquistadores only bothered to take a bath once a year. Cleanliness was definitely not their thing.

To me, the voluntary daily street cleanup in Querétaro was a shining example of civic pride and civilization and I cringe at what it is turning into in modern times thanks to the Japanese who, in the late 1950s, unleashed upon our planet a device which has frequently been called “the most idiotic invention of all time:” the leaf blower.

The origins of this reverse vacuum-cleaner are shrouded in mystery. Some say it was first developed to disperse agricultural chemicals while others claim it was used to remove debris from delicate Japanese gardens. The inventor is said to be one Dom Quinto, about whom, it seems, not much is known. Perhaps he went into hiding to avoid being lynched by millions of people who can’t stand his contribution to noise pollution.

At any rate, when the device reached the U.S.A. it was, in some areas, at first considered a useful tool for piling up leaves in the late autumn. Although the gizmo was noisy and its emissions excessive, it was considered tolerable because it was used for only a few weeks out of the year.

Then it crossed the border into Mexico, where it was immediately pounced upon as a blessing from heaven, a quick, easy and irresistible solution to the daily task of keeping the ground clean outside one’s door. Designed for use only a few days out of the year, the nerve-racking, noisy leaf blower was transformed into a Power Broom and is now used every single day by countless Mexican workers (a few wearing masks, none wearing earplugs) who are forced by economic necessity to spend eight hours a day pointing a howling and shrieking machine at every speck of dust they find lying on the ground.

I have a neighbor who employs not one but two leaf-blower-wielding gardeners at the same time to lift the dust from the great stretches of concrete pavement surrounding her house. “How could I possibly keep all this clean without these machines?” she told me. “I can’t live without them.”

Unfortunately, the leaf blower was never designed to be a dust mop and thousands of well-meaning users in Mexico are literally stirring up clouds of trouble for themselves and their neighbors.

All you have to do is to take a look at the contents of what leaf blowers raise into the air. Streets and sidewalks are covered with minute particles of dirt, pesticides, fungal spores, mold, insect eggs, pollen, fertilizers, brake-pad fibers, dried urine, spit and vomit, plus the excrement of dogs and the droppings of birds, mice and bats, just to name a few ingredients.

In addition, lead, arsenic, mercury, heavy metals and other carcinogenic substances have been found in the 5 pounds of particles which a leaf blower launches into the air every hour with the force of a hurricane.

The dust can take hours and even days to settle. These particulates aggravate allergies and asthma. They also contribute to cardiac conditions such as arrhythmia and can cause heart attacks. Moreover, they contribute to pulmonary diseases such as bronchitis, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

In addition to the disgusting material the leaf blower lifts into the air, the emissions of its engine are way off the chart. Air pollutants coming out of a gasoline-powered blower for only half an hour are equivalent to those emitted from 885 kilometers of automobile travel (California Air Resources Board).

This means that if your fraccionamiento employs just two men to “dust off” your streets eight hours a day, they will pollute the air every month with the equivalent emissions of a car traveling 680,000 kilometers, nearly twice the distance from Earth to the moon.

As far as gardening goes, experts say the leaf blower is the very worst imaginable device to put near a plant. Wind coming from the nozzle is hot, dry and moving at about 290 km/h, the speed of a hurricane or tornado. It kills soil-dwelling organisms, they say, and is exceedingly harmful to plants.

Last but far from least comes the outrageous noise of the leaf blower, which is as endearing to many people as the whine of a dentist’s drill. Leaf blowers produce a noise level of 70-75 decibels at 15 meters. They can cause hearing loss at this distance and, of course, result in eventual deafness to the operator if, as is so common in Mexico, his ears are unprotected.

The damage caused to bird life has yet to be assessed. According to Francisco León, the man in charge of the Audubon Society Christmas Bird Count in Guadalajara, “Our statistics are beginning to show a drastic reduction in bird life wherever leaf blowers are regularly used. These obnoxious machines are chasing away many birds and possibly other kinds of animals and insects as well.”

Because of all these factors, Mexico desperately needs to find a modern device that will satisfy the demands of the Spotless Sidewalk Syndrome without causing pollution, pulmonary diseases, lung cancer and deafness.

If we have succeeded in exploring distant planets and splitting the atom, surely someone can come up with a quiet, non-polluting way to remove dust and dirt as efficiently as the 1,000 silent street sweepers of Tenochtitlán.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.