San Juanito Escobedo is perhaps the archetype of the quiet unassuming, forgotten pueblito located in the middle of nowhere.

That “nowhere” just happens to be within the bounds of what was once Mexico’s third-largest lake, La Laguna de Magdalena, which was drained in 1936 to create great stretches of flat, arable land.

This being the case, I was surprised indeed to receive the following message from my friend Rick Echeverría.

“John, have you visited the big distillery in San Juanito? If you do, don’t miss their tequila-aging cava — it may be the biggest in the world.”

I soon learned that the distillery is called Agave Azul, and I was kindly invited to tour the place by members of the García family, which runs the business.

Agave Azul and San Juanito are located 60 kilometers west of Guadalajara. Google Maps took my friends and me right there but via a truly adventurous route, including dirt roads and back streets that tested the mettle of our four-wheel-drive vehicle.

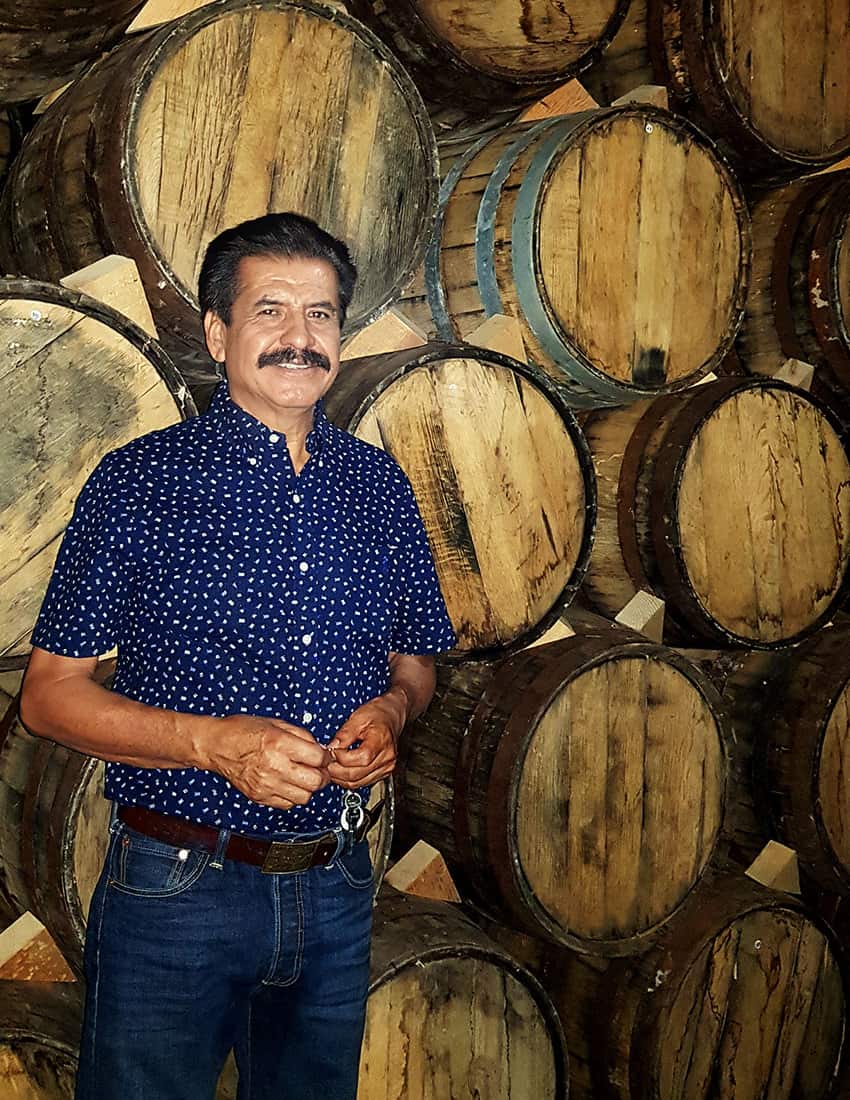

But after bouncing over the last pothole of a rut-ridden back alley, we suddenly arrived in front of a huge, modern industrial complex, and there we met José de Jesús García García, owner of Agave Azul.

“Our aim,” Señor García told me,” is to preserve the traditional way of making tequila, using stonework ovens and stills, the historical approach.” He added that many distilleries buy their agaves from others, but not his.

“Just look out the window and you can see hills covered with our agaves azules [blue agaves], 500 hectares of them, to be exact.”

García then surprised me by announcing that all those agaves are organic.

“We fertilize them with compost made from our own waste products, from our own bagasse [in this case, the shredded fibers of the agave hearts]. So we are returning to the soil what we have taken out of it, and we are not contaminating. Instead of killing the land around us, we are enriching it, we are making it more productive.”

José García then launched into the story of how this tequilería came into being, and quite a story it is.

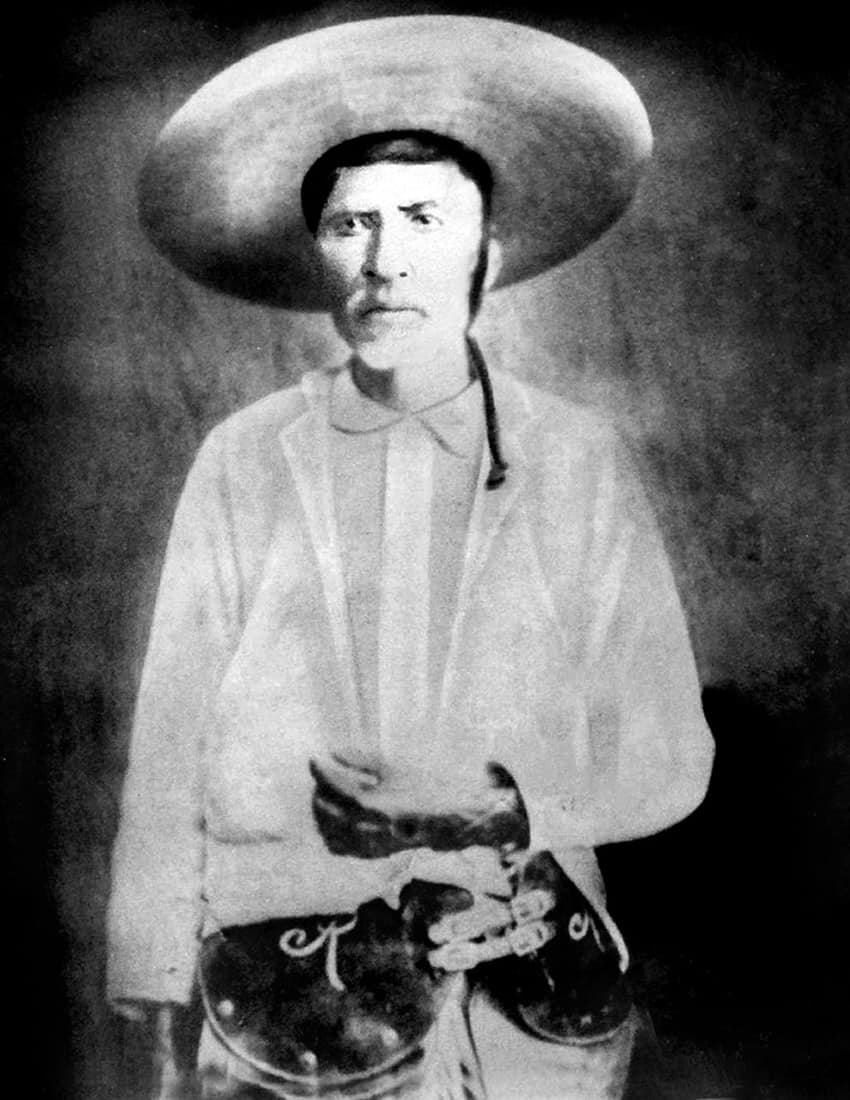

” I am the great-grandson of Don Anselmo García. I didn’t know him because I was born in 1957, a few years after he died, but he was a craftsman. He produced and sold all sorts of artesanías made from tule, the reed that used to grow all around the edge of the Laguna de Magdalena.

“He made petates [sleeping mats] and sopladoras [hand fans for stoves and fireplaces] and curious-looking chinas that served as raincoats in bygone times. Don Anselmo would travel all around this area, selling his products of tule along with queso enchilado, which is so called because the outside of this cheese is literally covered with chile for two reasons: first to make sure flies don’t land on it, and second to preserve its correct consistency. This procedure, in fact, preserves the cheese for over a year.

“Now, one day, when my great-grandpa was in Tequila, Don Javier Sauza said to him: ‘Why don’t you plant agaves in your pueblo?’ And it was because of him that agaves were introduced to San Juanito.

“So my bisabuelo [great-grandfather] brought someone here to show people how to plant and cultivate and harvest agaves. Years later, when the first of them were ready for harvest, they set up what we traditionally call a taberna here, with distilling equipment made of copper.

“But all of this was for friends, and they didn’t call it tequila; they called it aguardiente [firewater]. Then my great-grandfather died, and that was the end of the taberna.”

José García told me that friends of the family eventually revived the taberna and even got him involved in the project, but he never knew that the distillery had anything to do with his great-grandfather “until one day, I ran into my great-uncle and I said: ‘Uncle, why don’t we have a little drink?’ And he replied, ‘But where can we go?’

“‘To the tequila factory,’ I answered.

“‘What factory? You’re crazy.’

So they got into a truck and headed along a little dirt road in the middle of nowhere.

“… my great-uncle says, ‘Isn’t this Los Reyes?’”

When García replied that it was, the great-uncle said, “Bueno, Los Reyes is the place where my father used to make a really good aguardiente.”

“And that is when I put it all together,” García explained. “I understood that this distillery where I was helping out was, in fact, the very same [one] my great-grandfather had set up years ago. That is when I decided to take up what my great-grandfather had been doing and to make it my own. Now, finally, we are completing the obra [life’s work] that he began a long, long time ago.”

After hearing this story, we went on a tour of the distillery, following the process whereby the piñas de agave are cooked in a huge stone oven, crushed and squeezed dry. Then the juice goes into fermenting vats, followed by distillation in huge alambiques, or stills.

All these works are built on a hillside to take advantage of gravity, with the final product ending up in their cava. There it is aged in oak barrels from France and the United States for up to three years.

This cava — which is accessed via a long, spooky passageway right out of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Cask of Amontillado — is a huge underground room that provides the perfect temperature (10 to 13 C) and conditions for aging.

In other distilleries, over 10% of a barrel of tequila is lost to evaporation every year, but deep underground, this phenomenon is greatly reduced.

After touring the distillery, we went off to the composting facility located five minutes away. Here, in front of row after row of composting beds, we met Luis Ángel Ruvalcaba, who explained how Agave Azul makes its own fertilizer.

Most other tequila makers throw away their bagasse and their distillation slops (the top and bottom portions of the fermented must or wort). Not Agave Azul.

It sends all of it to Ruvalcaba, who mixes it with cow, sheep and rabbit manure and bat guano and spreads the mixture on top of the composting beds, where countless California red worms transform it into the very best fertilizer imaginable.

None of Agave Azul’s waste products are dumped into local rivers. The river outside the town of Tequila is badly polluted.

While many tequilerías are concentrating mainly on volume, this one, and a few others I’ve seen, appear to have a genuine concern for quality.

“Yes, you can find something called tequila on the market for US $10 a bottle,” Aldo García told us,” but what is it made of?”

He explains further: “Just do the math: to make one liter of tequila, you need more or less seven kilos of agaves, and each kilo costs 30 pesos, so the mere cost of the raw material is 210 pesos, a little over $10.”

Just what the biggest distilleries — most of which are no longer owned by Mexicans — are pouring into those liter bottles, I can’t say, but if you would like to taste what Agave Azul is producing in San Juanito, look for their brands: Don Anselmo, La Tarea, Chulavista and El Pial, all available both in Mexico and in the United States.

¡Salud!

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.