Having lived here for over two decades now — and becoming a mother myself during that time – the institution of Mexican motherhood is something I’ve had a chance to observe up close, as well as participate in on a social, emotional, and visceral level.

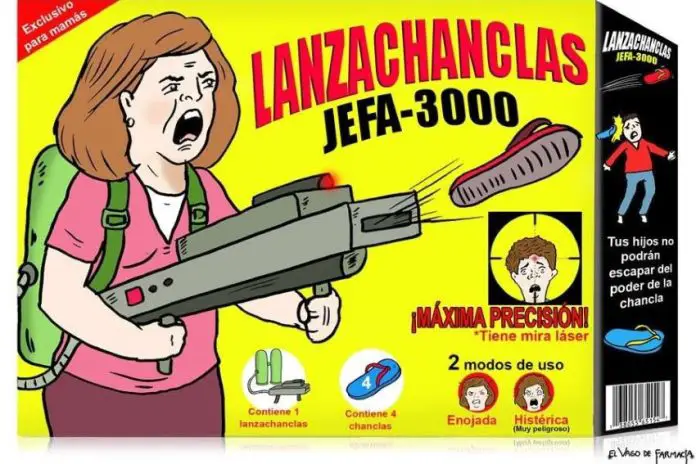

I’ve seen the roots of some of our most famous stereotypes (beware the flying chancla!) and the realities of what it really means to raise a child here (spoiler alert: guilt and paralyzing fear are universal mom feelings).

Many people, even those who don’t live in Mexico, will be familiar with Mexico’s patron saint and most popular archetype of the perfect mom: la Virgen de Guadalupe. She is selfless. She is doting. She will sacrifice anything for her children, who are her greatest loves (Joseph who?).

The idea of “traditional” Mexican motherhood is rooted in the reverence of the characteristics exemplified by la virgen, and women were long expected (and sometimes still, unrealistically expected) to wait on their children hand and foot, who, by the way, could do no wrong.

Well, the male children, anyway. The girls would typically be put to work learning the arts of homemaking, cooking, and childcare, the assumption being that they needed to be trained to serve their future husbands and children.

Another prominent characteristic of Mexican motherhood is one that I’m still occasionally caught off guard by: children are treated as very young children for a long, long time. You might have noticed manifestations of this in the form of male children as old as nine going into the women’s bathroom with their mothers in public places, for example, or hearing mothers say things like “I’ve got to get home to bathe my children” (who are quite a bit older than five).

But things are changing: Mexico’s economy, just like most other economies in the world, rarely provides for salaries large enough to provide for the needs of an entire family these days; increasingly, households require two working parents in order to make ends meet. Unfortunately for mothers’ nerves, the expectations of what it means to be a “good mother” haven’t changed all that much despite this shift.

This means that many of those perfect mother ideals simply cannot be met, though there are plenty who try: most all of my close mother friends struggle mightily to provide home-cooked meals — the only kind of food you give your kids if you truly love them around here, it would seem — and to sit with them to help with homework.

This economic reality has also given way to a new archetype: the mamá luchona (“struggling mom” — typically used sarcastically) often characterized as a young mother who leaves her children with her own parents or whoever else is willing to raise them while she goes out to work, study, party and date (I’m sure you can guess which of those activities mothers are accused of the most).

And now with the exploding popularity of social media like TikTok and Instagram, we all get to see another stereotype of Mexican motherhood: that of the constantly screaming mother who runs a tight ship but cares nothing for her children’s emotional well-being.

Her children act respectfully because they are afraid of her, sure that they’ll be in for a chanclazo (basically, getting a flip-flop thrown at them, or just being hit with it more directly) should they do or say the wrong thing.

The videos on this subject are meant to be comical, and they are. The subtext seems to say, “We Mexicans aren’t emotionally coddled as children like our neighbors to the north; the rules don’t change because we have feelings about them.”

I will say this: when you’re busy working as well as being a mother, it’s tough to keep your kids in line, and yelling often ensues. I’ll admit that I’ve noticed this within my own circle of friends (and, occasionally, myself), most of my mom friends, even if they do everything for their children, really let their kids have it (verbally — I have yet to witness a flying flip-flop) when they mess up.

I’ve heard some of them talk to their children in ways I wouldn’t dream of talking to mine, and can’t help but wonder if it will be something they are talking about on a therapist’s couch in 15 years. But I also see them going above and beyond for their children in ways that I do not, providing for some striking contrasts among our various sensibilities.

In the end, all stereotypes come from somewhere, from the chancla-throwing, hot-tempered Mexican mother to the coddling, feelings-first “gringa” mother whose children can get away with just about anything if they manage to convince her that it’s imperative to their mental health. But the realities of motherhood are always so much more nuanced than they appear, and there’s one thing we all have in common with la virgen: a fierce love for our children and a willingness to do just about anything for them.

So in the wake of Mother’s Day, just remember: we really are all doing our best.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com.