“We are our own stories,” says Lupe Puc, a Maya elder. “And the medium is not important; it’s the sharing of who we are that makes us.”

For the indigenous communities of Mexico, storytelling is the most crucial means available for exchanging knowledge, and now — with the help of filmmaking technology — for sharing their stories more widely.

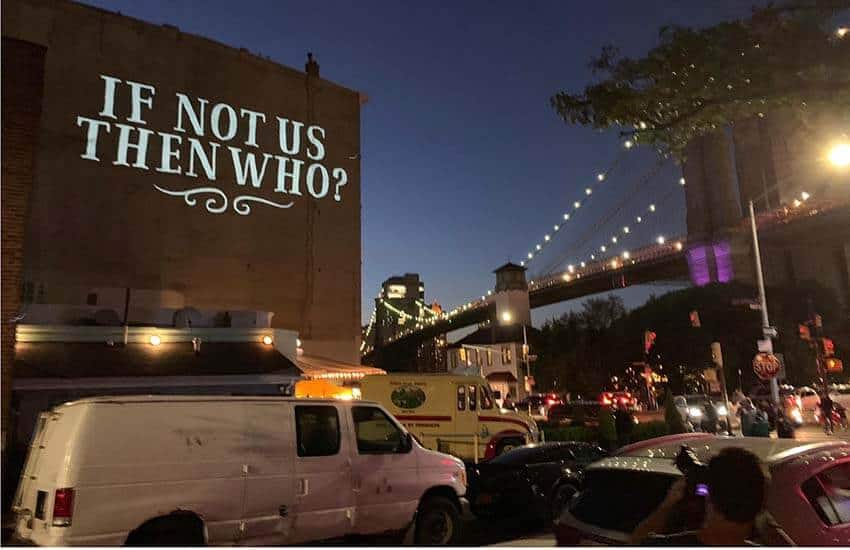

Since 2014, the innovative and groundbreaking film production company If Not Us Then Who (INUTW) has been producing films that identify and empower individuals the world over — including in Puebla — enabling voices that highlight the role of indigenous communities as stewards of their lands and raising awareness for their political plight.

“As the climate crisis hurtles towards disaster,” explains Puc, “and the rights of rural communities are being bulldozed by government corporations intent on expansion at any cost, it is vital that communities are able to represent their own perspectives, and INUTW is helping to achieve that.”

If Not Us Then Who began as a production company known as Handcrafted Films, run by British filmmakers Paul Redman and Tim Lewis. Lewis now works as the organization’s general director.

In the beginning, Redman and Lewis were idealistic travelers dreaming of using documentary filmmaking as a forum to raise the voices of the communities they visited when they reached the Philippines: there they had seen firsthand the widespread deforestation caused by palm oil plantations.

They began documenting the impact on the people there. But, despite their best efforts, they found that there was something missing.

INUTW’s regional coordinator Thalía Castillo explains that it came down to who was telling the stories.

“They were trying to be as faithful as they could to the authentic point of view of the communities, but as a filmmaker you can never step out of your own perspective. So the goal changed; it became about teaching people in communities to be communicators and to make the films themselves so that they could spread their voices globally.”

And so began, slowly, the process of training people to create their own documentaries.

Initially, training was informal, but when, years later, the young people they had worked with began to produce short films, it became clear that there was scope for a new dream.

Thus was born the Emerging Filmmakers Professional Development Programme, which uses master classes and workshops to support indigenous storytellers and grassroots collectives in their resistance to land dispossession and climate threats. The films allow remote indigenous communities in many parts of the globe to open a dialogue between land and environmental defenders — who are the frontline against the impacts of climate breakdown — and policy makers.

INUTW is currently mentoring 20 people from Central America, Brazil, and the Philippines. In addition, there is a program operating in the Cruz de Ocote ejido (communally owned land) in Ixtacamaxtitlán, Puebla, where activists are campaigning against the immense destruction to community-managed forests posed by a mining concession.

In partnership with the Mexican NGO, the Project on Organization, Development, Education and Research (PODER), INUTW provides the trainees in Puebla with equipment to film. It is then the people on the ground who formulate questions, conduct interviews and shoot footage.

This campaign is largely designed to reach the Mexican government, as well as to raise the voices of the communities in Puebla in international forums and with leaders who might otherwise never learn of their realities.

After the pandemic last year forced the world to retreat inside, the importance of storytelling has never been more apparent, or more pressing. For INUTW, 2020 proved remarkably fruitful: the switch to online mentoring and distribution brought about a surprising level of expansion.

Undoubtedly, COVID-19 significantly worsened many of the environmental and land-rights issues threatening rural indigenous communities and led to the immediate losses of community members to the virus. However, having to innovate ways of coping with being unable to interact face-to-face allowed filmmakers and organizations alike to evolve and to test the horizons against which they set their goals.

“From what I can see,” says Castillo, “the internet allowed us to expand more widely in a way we didn’t think was possible before. We had a dream to train people from communities, and we’ve been evolving. But with COVID, we couldn’t go to the communities.

“Yet the lockdown gave aspiring filmmakers time to create, and the digital age allowed us to spread their stories. I’m not saying that virtual is better — of course, it can’t replace person-to-person interaction — but it has been valuable.”

Castillo reflects that film is uniquely situated as a medium for indigenous stories to be told in a time when people are struggling to reach each other face-to-face, as well as to express the diversity of the indigenous cultures in Mexico.

“There is no one indigenous culture,” she said. “We’ve always known that there are different stories to be told.”

Perhaps most valuably, then, the work done by If Not Us Then Who highlights that the world needs resilient storytelling. At heart, INUTW is a team of driven people who want to do good things and who believe in the power of storytelling as the most important tool we have to raise the voices of indigenous communities across the globe.

“It is a breakthrough to be able to work directly with such inspiring people on the ground — where things are actually happening,” says Castillo, “and to be able to watch the change that it creates.”

Shannon Collins is an environment correspondent at Ninth Wave Global, an environmental organization and think tank. She writes from Campeche.