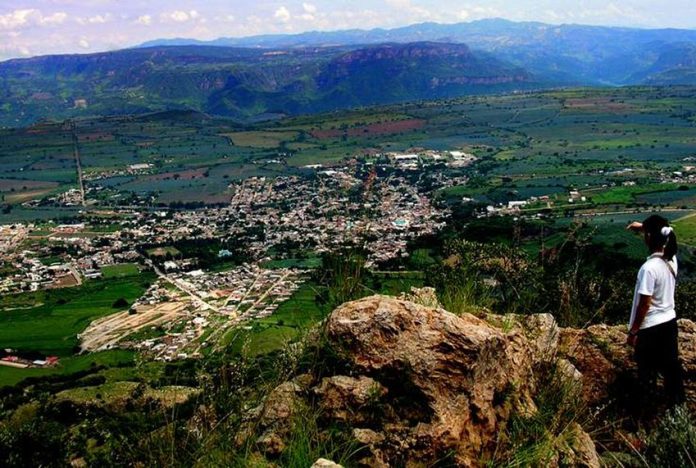

The small Jalisco town of Amatitán is not designated a Pueblo Mágico (magical town) but it seems every time I visit it I discover something curious and interesting.

Amatitán is located 33 kilometers northwest of Guadalajara. The first time I went there I was surprised to find the plaza at its far eastern end. “Why isn’t the town square in the middle of the town, like everywhere else in Mexico?” I asked the local public relations man, Ezequiel García.

“It’s because of the water,” he said, guiding me to a rustic pool at one end of the plaza. “In bygone days this was the only source of water in all of Amatitán and people came here to fetch it. By the way, you might be interested to know that this water flows out of several man-made tunnels dug into the hill next to the plaza.”

This interested me greatly because I have had several opportunities to study some of the underground aqueducts or qanats that have been used all over Mexico to bring water to dry pueblos.

García showed me a plaque near the pool, which explained that qanats were invented in Persia thousands of years ago and the qanat technology proved so successful that it literally spread across the world to Arabia, to China, to the Roman Empire and via Spain to the Americas.

When I discovered that no one had ever mapped the passages of the qanat de Amatitán, I offered to survey it using techniques I had long employed for mapping caves. Here are my notes on that experience:

“Our survey moved along quickly because these man-made passages — unlike those of a natural cave — went in straight lines. We had hoped our boots would keep us dry, but the water on the floor turned out to be knee-deep and a cool 17 C. After 64 meters, the flooded main passage turned right and got a bit deeper.

“That’s when we spotted live wires, connected to the electric lights installed in this tourist attraction, disappearing into the water we were standing in. Well, over the years cave exploration may have presented us with certain problems, such as puddles of evil-smelling vampire guano and ‘lakes’ of suffocating carbon dioxide, but at least we’d never been in danger of being electrocuted while standing in two feet of water!

“In the end, though, we survived and our survey showed that this qanat has four passages totaling 113 meters, with an air temperature of 18 degrees and 83% humidity, should anyone be interested.”

“We have another tunnel like this in town,” Garcia casually mentioned when I presented him with a map of the qanat — and that is how we discovered a second fascinating spot in Amatitán called El Chimulco. This tunnel was most interesting because its waters were channeled to a pool inside a “casco de hacienda” (mini-hacienda?) which had been built by the leading local families for swimming, dining and relaxing.

A few years ago, these scenic ruins were transformed into “Restaurante Ruinas de Chimulco,” which is open Friday to Sunday. When we went to eat there — after touring the qanat, of course — we were visited at our table by one of the owners of the place, Mayra Rosales.

“These ruins are almost 300 years old,” she told us. “They go back to 1729. As you can see, the style here is Arabian. You can find pools like this, enclosed by four walls, in Morocco. The roof above us is vaulted and no beams were used to support it. I came to this place when I was eight years old with my mother, who would bring a tubful of clothes here to wash. All along the river that flows out of here were rustic ‘lavaderos de piedra,’ flat rocks set up for washing clothes with a brush and soap and I helped my mother do this chore with a little bucket I would fill up and pour out.”

She pointed to two tall pitayos (cacti) growing on the wall above the pool. “I remember looking up at those pitayos as a little girl — and they are still here! When my family bought this land, my husband said we have to remove those pitayos because they could fall on top of somebody. But I replied, ‘Look, if they haven’t fallen down during 50 years, they’re never going to fall down.’ So they are still here.”

After enjoying a meal at the picturesque ruins of Chimulco, you may want to stroll over to Amatitán’s Museo de las Tabernas, located just north of the plaza. To my delight, I found things explained here both in Spanish and in English.

Tabernas, I learned, is the word first used to describe mezcal distilleries in this area, and Amatitán is surrounded by them. Local researchers point out that it was their ancestors who first employed the famed blue agave tequilana to make spirits. “That agave is native to our Tecuane Canyon,” they insist, “and what is now called tequila was first made here.”

One of the surprising things about this museum turned out to be its gift shop where, for the first time, I was able to see in one panoramic view all 18 brands of tequila which are being produced in and around this little town.

After visiting the Museo de Tabernas, plan some time for wandering around the town’s beautiful back streets which, in my opinion, are charming enough to qualify Amatitán as a Pueblo Mágico. In the most unexpected places you will find plaques, again in both Spanish and English, like the following, written in 1795, which describes the benefits of drinking tequila:

[soliloquy id="64603"]

“Is this drink bad for you? It is not. (At worse, it) inebriates and causes lethargy. The same happens with the finest wines from Spain and no one has said that is harmful to your health. Drinking mezcal in moderation, as one should . . . is good for the stomach, comforting and medicinal and as such is recommended by doctors. I have tried it and know that it is helpful.”

Who wrote this? Anyone reading the often curious and interesting plaques along the streets of Amatitán would know it was none other than Esteban Lorénzo de Tristán, bishop of Guadalajara, in a letter to the Spanish viceroy.

By now you may think that I have surely exhausted all the charms of Amatitán, but in reality I haven’t had a chance to talk about the great Mexican architect Luis Barragán, who just happened to have an aunt living in this town. He consequently created numerous obras in the local church and elsewhere, each well worth visiting.

Oh, and did I forget to mention that Barragán dragged his friend, the famed muralist José Clemente Orozco, to Amatitán, insisting he do a few paintings in the church? Well, I won’t go into it, because they say Orozco was so put off by the unfriendly attitude of the local priest (“I’d rather leave these spaces blank than let you paint anything here!” the padre supposedly said) that he ripped up his sketches and marched out of the church. As a result, Orozco’s grandson told me, “My grandpa never painted anything in Amatitán.”

All of this could make you suspect that Amatitán has more to offer than first meets the eye. If you want to see for yourself, you’ll find the church listed on Google Maps as “Inmaculada Concepción Parish.” The Museo de Tabernas is called “Museo Interpretativo del Paisaje Agavero” and the qanat-cum-restaurant is “Ruinas Chimulco Restaurante.”

As for the claim that Amatitán is the birthplace of tequila, it’s necessary to examine a few of those old tabernas in the valleys and canyons outside the town, and this I propose to do in my next article.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.