Filogonio Naxín may have found a way to make the old myths relevant to the modern world.

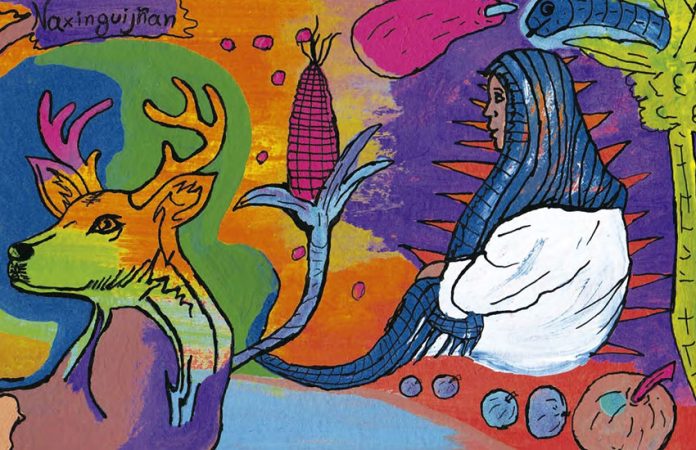

Born Filogonio Velasco Casimiro in 1986 in the village of Mazatlán Villa de Flores in the Sierra Mazateca of Oaxaca, Naxín grew up listening to the stories of his elders. One very important concept for his Mazatec community is the nagual, a being that crosses the line between human and animal. Fascinated by these stories, he began to draw them as a child.

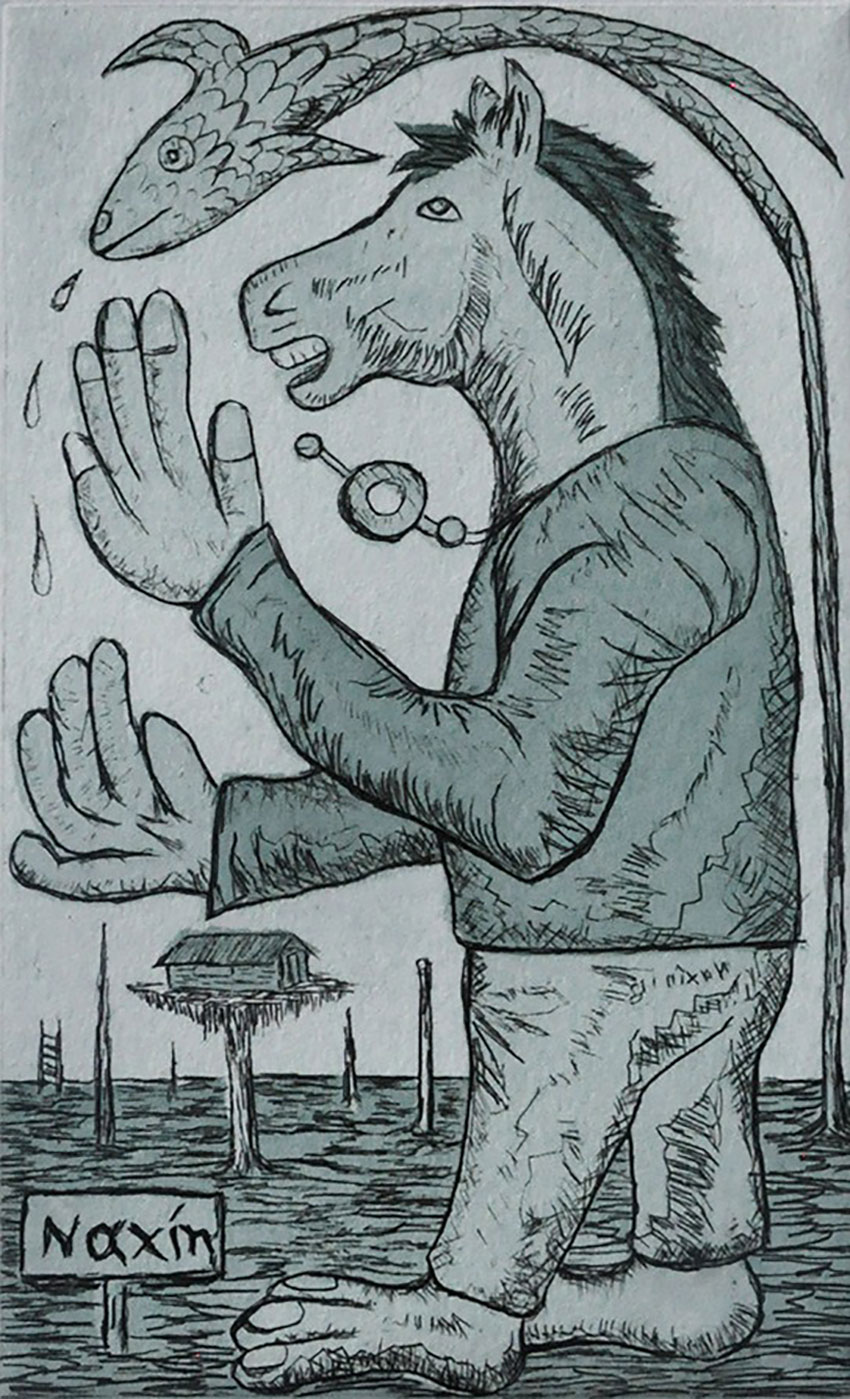

Naxín’s nagual or spirit animal is the horse, called naxín in Mazatec.

Naxín’s world was completely in Mazatec until at age 11 he started school, which of course is conducted in Spanish. Initially unable to understand his teachers, he would pretend to be paying attention by drawing in his notebooks.

As an adult Naxín tried his hand at such jobs as cashiering and working as a butcher, and he even took the test to become a police officer (he did not pass). Fortunately he decided to study fine art at the Benito Juárez Autonomous University of Oaxaca (UABJO) despite meager economic resources. Materials scrounged from his jobs, like paper, cardboard and even animal blood were incorporated into his class projects.

He graduated in 2005 but says that his time with the university served to confirm much of what he learned by trial-and-error drawing as a child, adding theoretical concepts to it. It has not changed how he works. As in the notebooks, his drawings, paintings, collages and graphic works have no preliminary sketches. If the images are lopsided or otherwise twisted, that is how they are meant to be.

But Naxín’s time outside of his village has served to help him bridge the gap between the Mazatec world of his childhood and modern life. As a result, his naguals and other images serve to comment on modern life rather than being a frozen artifact of the past.

Naxín’s work has a broad range, utilizing different media for different purposes and different audiences. It can be classified by media and message but there are two constants running through it: the preservation and promotion of Mazatec culture (and by extension all of Mexico’s indigenous cultures) and commentary on the issues of modern Mexico.

Naxín’s focus on tradition and identity is clearest in his work for children. In his first book, people and naguals appear but in a way that is attractive and minimally challenging to the onlooker.

His art dealing with political and social issues for adults is much grittier. The style is modern and would not be out of place in a street mural or comic book.

Because the use of animals is not limited to Mesoamerican cultures, the mixing of them with human imagery has a global appeal. Other images that pull outsiders in include oversized hands, pillars and columns, vegetation, broken stairs, modern weapons, surrealistic elongated bodies and the artist himself (almost always appearing as a horse).

Naxín believes the use of the Mazatec language in his works and exhibitions is important though it may carry different meanings for Mazatec and non-Mazatec speakers. A speaker of Mazatec will get a very different sense knowing the exact meaning of the words but for non-speakers they add an other-worldly element, much the way that Chinese characters can. At the very least, they serve as a reminder that indigenous languages are still very much alive.

Although he began exhibiting in 2006, his career began to take off after he moved to Mexico City in 2013, with his first major show there in 2014 at the Autonomous University of Mexico City. Since then he has had major shows at the National Autonomous University (UNAM), private galleries and public museums. His success in the capital enabled him to stage individual shows back in his native Oaxaca. This is important as his work does not fit in with the prevailing Oaxaca school.

Living in Mexico City gives him opportunities to work in illustration, both with his own projects on Mazatec culture and work by other writers. In 2018 he illustrated Cicatriz que te mira by poet Hubert Martínez Calleja, which was presented at the Palacio de Bellas Artes. He and his work are gaining notice, with features in such Spanish-language publications as La Jornada Ojarasco (2018), Arqueología Mexicana, Mexicanísmo and even Playboy México (2020).

Living in the capital does not mean leaving Oaxaca behind. Naxín returns regularly to teach children in his hometown, something he called “an act of resistance,” as indigenous communities have no access to artistic training. He believes this knowledge is important to his community as it grants the culture a voice.

Filogonia Naxín’s work is on exhibit at FES Acatlán (UNAM) in Naucalpan, México state, until April 24.

Mexico News Daily