Although Americans continue to relocate to Mexico searching for a better quality of life, there are hundreds of thousands of U.S. citizen children and former U.S. residents living in the country today who didn’t choose to move here. These are primarily people of Mexican heritage who were forced out of the United States and are now living in a state of limbo between the two countries.

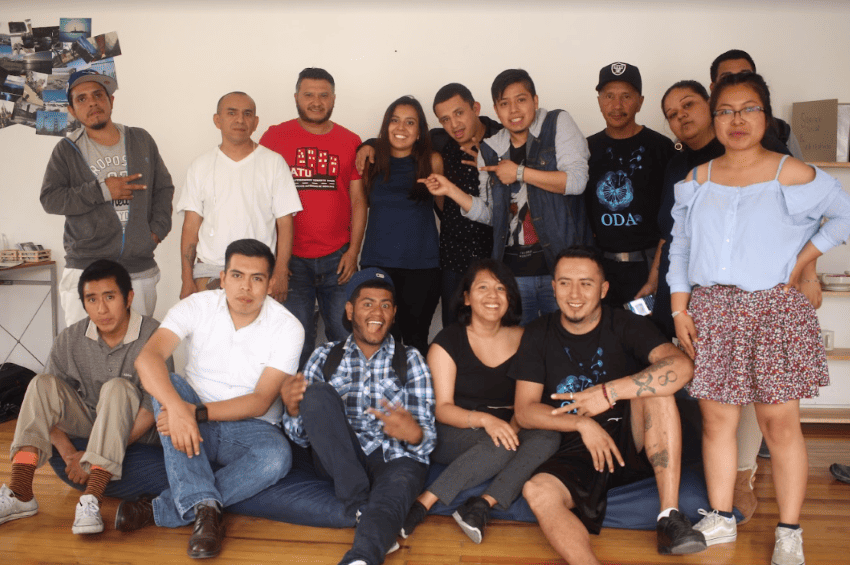

Organizations such as Otros Dreams en Acción are dedicated to supporting returnees, deportees and new arrivals from the U.S., providing them a place of community, belonging and assistance integrating into Mexican society. That means everything from obtaining travel visas and citizenship to helping new arrivals learn Spanish. Many of ODA’s staff are among those forcibly uprooted from the U.S., such as Madai Zamora Candia.

Zamora lived with her family for 21 years in the United States and had recently completed her university degree when she was forced to move back to Mexico — a country she hadn’t lived in since she was three years old. She struggled to get her degree recognized by the Mexican government and her identification card to begin a new life in what was essentially a foreign country for her. She now lives in San Luis Potosí and is an advocate for other displaced Mexicans and U.S.-born children of Mexican nationals as ODA’s Community Engagement and Organizing Coordinator.

“Even though the Mexican government loves to say they support returnees and that they give us an ID when people are deported, they don’t. They give us a piece of paper (known as the “constancia de recepción de Mexicanos repatriados“) that no one accepts. You can’t open a bank account with it, you can’t rent an apartment and you can’t get hired for a job,” said Zamora.

Zamora is one of the hundreds of thousands of Mexicans and U.S.-citizen children of Mexican nationals who are navigating the challenges of integrating into a society that isn’t truly prepared to welcome them back.

“The preconception is that if you return to ‘your country’ it will be easier. You are supposed to know your place. But many people have been away from Mexico for a long time. Half of the undocumented population has lived in the U.S. for more than 17 years. So Mexico is a new place, even if you have Mexican nationality or heritage,” said Dr. Claudia Masferrer, Professor and researcher of migration policy at the Center for Demographic, Urban and Environmental Studies at El Colegio de México.

Returnees, deportees and new arrivals not only face bureaucratic hurdles but also often endure discrimination, family separation, restricted movement between the U.S. and Mexico, emotional distress and culture shock. Some don’t even speak Spanish.

“There are so many layers — from bureaucratic and emotional to territory and place complications. Some people aren’t even returned to where they are from,” said Luisa Martínez, a U.S.-born daughter of Mexican parents who was raised in Tijuana. Martínez is now the Coordinator of Florecer Aquí y Allá — an arts and narrative program supported by ODA. “There are only a few organizations like ODA that focus directly on returned and deported people.”

ODA helps fill the gaps where the government and other NGOs fall short, providing new arrivals assistance with obtaining Mexican citizenship, identification cards, education level validation, employment, housing and much more.

The organization works through a model of “acompañamiento” (accompaniment), meaning they support new arrivals through every step of their journey and continue to be a source of support long after arrival. It’s a holistic approach that recognizes the importance of meeting the varied needs of the community, including their social and emotional needs.

“There is a lot of loneliness when you come back. I never found a support group or someone I could relate to, even though I’ve been back in Mexico for 20 years. Finding ODA and other people that share this experience is important,” said Baruck Racine Arellano, who runs ODA’s Pocha House, a community gathering space in Mexico City that hosts art, writing, poetry and zine-making workshops, book readings and other events.

Since 2018, ODA has provided sustained support to 386 people in Mexico City and hundreds more across the country and the U.S. The organization focuses on both adults and children, including U.S.-born children, about 500,000 of whom currently live in Mexico.

Dr. Masferrer’s research has found that U.S.-born children who have been “de facto deported” along with their Mexican parents experience even greater socioeconomic disadvantages than those who moved back for other reasons.

“U.S.-born minors should be welcomed better; they are the children of Mexican nationals,” said Dr. Masferrer. “There is a general lack of empathy for returnees and other foreigners. If Mexicans were able to welcome back their own, they would be more accepting of other foreign-born immigrants.”

ODA believes that everyone deserves a dignified return. The organization recently published the English-language report “Toward a Retorno Digno,” outlining its policy recommendations for creating the conditions for mobility with dignity in Mexico City and beyond. These include providing direct and unrestricted financial assistance to migrants, ensuring that banks and government agencies accept multiple forms of identity documents, providing shelters and temporary housing for migrants, increasing the minimum wage in Mexico City and implementing a family visitation and reunification program.

Family reunification is one of ODA’s primary areas of focus. Every year, ODA organizes a “Fight for Hugs” campaign, which raises money to help cover travel and legal expenses for people to reunite with loved ones in the U.S. and Mexico. ODA also operates the Visa Justice Program, where they accompany people through the tourist visa application process to try to obtain permission to travel to the U.S., a freedom taken for granted by other U.S. citizens who travel between the two countries with relative ease.

For people who have experienced deportation, and for almost all Mexican citizens, the freedom to travel between Mexico and the U.S. is severely restricted. People who have been deported are automatically banned from traveling to the U.S. for 10 years. Any Mexican citizen wishing to travel to the U.S. must go through an expensive and time-consuming visa application process and interview, and permission to enter the U.S. is not guaranteed.

“People coming to Mexico from the U.S. and other wealthier countries must realize the privilege they have and the difficulties for others. What you carry with you and how you contribute as a guest to this country comes with the responsibility of having that mobility,” said Luisa Martínez. “Mexico is providing people with a more manageable and cheaper life. Ask yourself: where do you put your income and how can you support a more equitable distribution of money and resources?”

People interested in supporting ODA’s work and its Visa Justice and Fight for Hugs campaign can donate directly to the organization via Paypal.

Debbie Slobe is a writer and communications strategist based in Chacala, Nayarit. She blogs at Mexpatmama.com and is a senior program director at Resource Media. Find her on Instagram and Facebook.