Fifty children from Oaxaca have just landed at Mexico City International Airport on a flight from Paris. They each carry a musical instrument tightly in their hands as they wait to board a bus back home to the town of Vicente Guerrero.

Their three-week-long tour of France saw the group perform over 50 concerts to packed crowds at a European classical music festival. For nearly all of the children who study at the Santa Cecilia Music School in Vicente Guerrero, a small village 12 kilometers south of Oaxaca city, this was the first time they had left Mexico.

Last year, the school’s orchestra and brass band gave a performance for President Andrés Manuel López Obrador during the opening ceremony for the country’s second-largest airport, the new Felipe Ángeles International Airport (AIFA). Seven recent graduates are now studying music at the Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and two recently began degrees at the National Music Conservatory in Mexico City.

This was far from the reality that the pupils and their families had imagined for themselves twelve years ago, when violence, gangs and drug abuse threatened to take control of the lives of many families in Vicente Guerrero. One resident tells me: “Before the Santa Cecilia Music School, the children had nothing to do. They would often be walking on the streets in gangs. There was a lot of trouble and a lot of pain.”

Before classical music came to town, the everyday beatwas dangerous and unpredictable. The town of 14,000 was known for being Oaxaca city’s municipal landfill site since the 1980s. To many, it was an abandoned outpost of the state.

Isabelle de Boves: A pilot with a passion for Mexico and music

Twelve years ago, a chance trip to the town by Air France pilot Isabelle de Boves, who was visiting her aunt, would alter the town’s future forever. “My aunt has always been a fearless heroine in my life. She has lived and helped communities in some of the most disadvantaged places in the world, and as a child growing up in France, I would always look forward to hearing her stories,” de Boves says of her aunt.

“When I arrived in Vicente Guerrero, [my aunt] took my arm, and we left her home and walked confidently through the town along several dirt tracks. The locals knew her face …she assured me we had nothing to worry about.”

“From a distance, I remember hearing major scales being sung in perfect harmony and a metronome-like rhythm being played in unison. We turned a corner and I saw a group of 21 singing children aged between 8-16 years old, using broken chairs and wooden sticks from the rubbish to keep the tempo. I’ll never forget their shining, lively faces as they played.”

The children told Isabelle and her aunt why they liked playing music and what their favorite instruments were. She was struck by their innocent, unwavering motivation to learn and equally saddened by their lack of musical instruments and resources.

On her return to Paris, Isabelle would begin her search for instruments. “In Europe, there are many families who have different instruments lying unused in dusty cases in attics or basements. It’s common that when children stop learning or playing music, many lovely instruments are left unused and unloved.”

Isabelle reached out to old friends and contacts, even adding the details of her hunt for instruments into her Christmas cards until enough had been secured to help build a small band.

Her next scheduled flight to Mexico City was planned for January 2012. Packing her maximum allowance for luggage with brass instruments and securing the support of her flight crew to do the same, 21 instruments donated by people across France were loaded into an Air France Boeing-737 destined for Mexico City.

“The cargo of instruments were stored safely in Mexico City for a couple of months until a bus could be organized to drive them for seven hours to Vicente Guerrero. When they arrived, I was sent photos of the children and hearing them play them made me so emotional.”

Isabelle de Boves would visit more and more in the coming years, bringing instruments and supplies and expanding the capabilities of the orchestra and band. She created a charity, La Banda de Música, to raise money for the school directly, and collaborated with European music teachers to organize for them to visit Vicente Guerrero for extended periods and teach masterclasses. Fundraising concerts took place across France to fund the construction of several new school buildings and the salaries of new music teachers.

Isabelle continues, “We are all so grateful for the continued generosity of people from around the world who helped us grow the school and take on more and more teachers and students, but none of this would have been possible without the backing and tireless work of the people in Vicente Guerrero.”

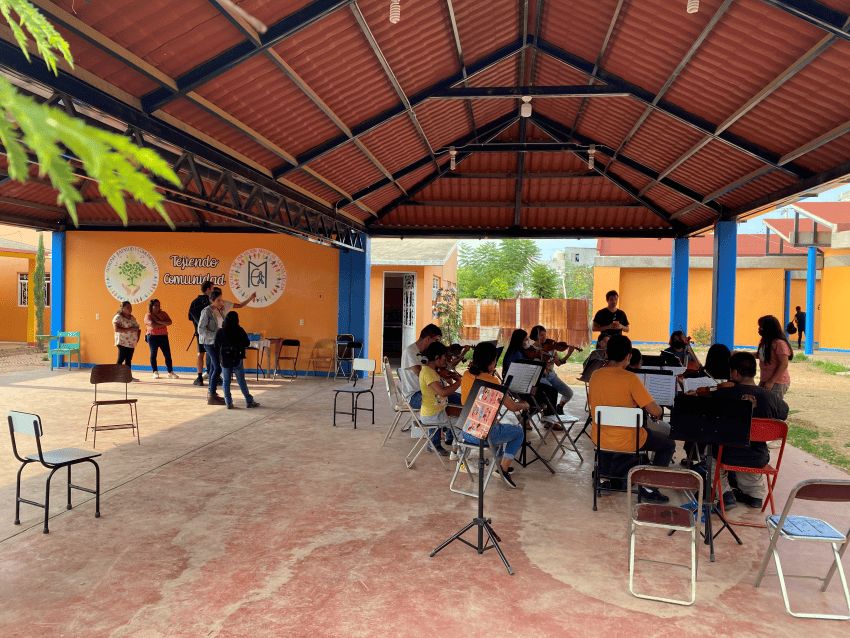

The close-knit community is deeply rooted in Zapotec culture, the largest Indigenous community in southern Mexico. Though the men and women in the town could not contribute large sums of money to support the school, they instead provided skills, hours of manual labor and often offered parts of their homes for rehearsal spaces. They gave a uniquely communal effort to help kids keep practicing while the building of the school progressed.

How music repaired the reputation of an almost forgotten outpost of Oaxaca

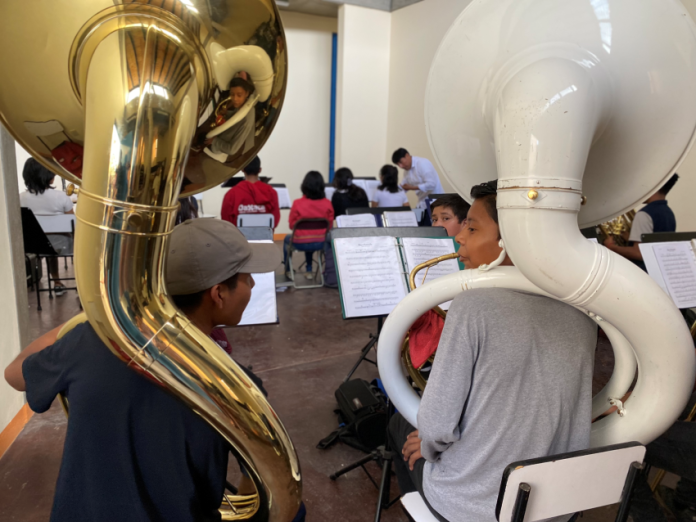

Today, the Santa Cecilia Music School has five large rehearsal rooms, an open-air performance stage, several classrooms and a luthier workshop, alive with jovial chatter and the sound of musicians warming up their instruments. One student, Armando (20) who was part of the 50-strong ensemble that performed in France, tells me about his memories of the violence before the project began.

“There was always violence on the street. I remember kidnappings, robberies and seeing more and more people taking drugs. If you went out on the streets at night here, you’d expect to get into trouble.”

Armando is charming and lively and always seems to be making his fellow students laugh during my visit to the Santa Cecilia Music School. Music has irrevocably changed his life, and he’s better off for it.

Signs of unrest still haunt the streets of the town after dark, and residents still recommend caution when visiting. Music has by no means solved all of the issues in Vicente Guerrero, but it has become a symbol of pride and unity for the disadvantaged town, which was once lost to its reputation as a dangerous municipal landfill site.

Gordon Cole-Schmidt is a public relations specialist and freelance journalist, advising and writing on companies and issues across multi-national communication programs.