The sun is beginning its descent when agro-ecologist Carlos Ramírez hops out of a truck outside Hampolol, Campeche. As he moves purposefully through the foliage alongside the road, there is little to be seen save for a handful of burnt palm trees blanketed in homogenous green vines — a reminder of the local practice of scorching the earth to open up land for planting.

The growth here will diversify eventually, but such an impenetrable layer of choking greenery will make it a slow process.

Beyond this outer edge of human agricultural encroachment, a sheer wall of jungle begins. As he walks into its tall shade, Ramírez’s tread becomes softer, and his footsteps can scarcely be heard over the awakened clamoring of the insects in the falling light.

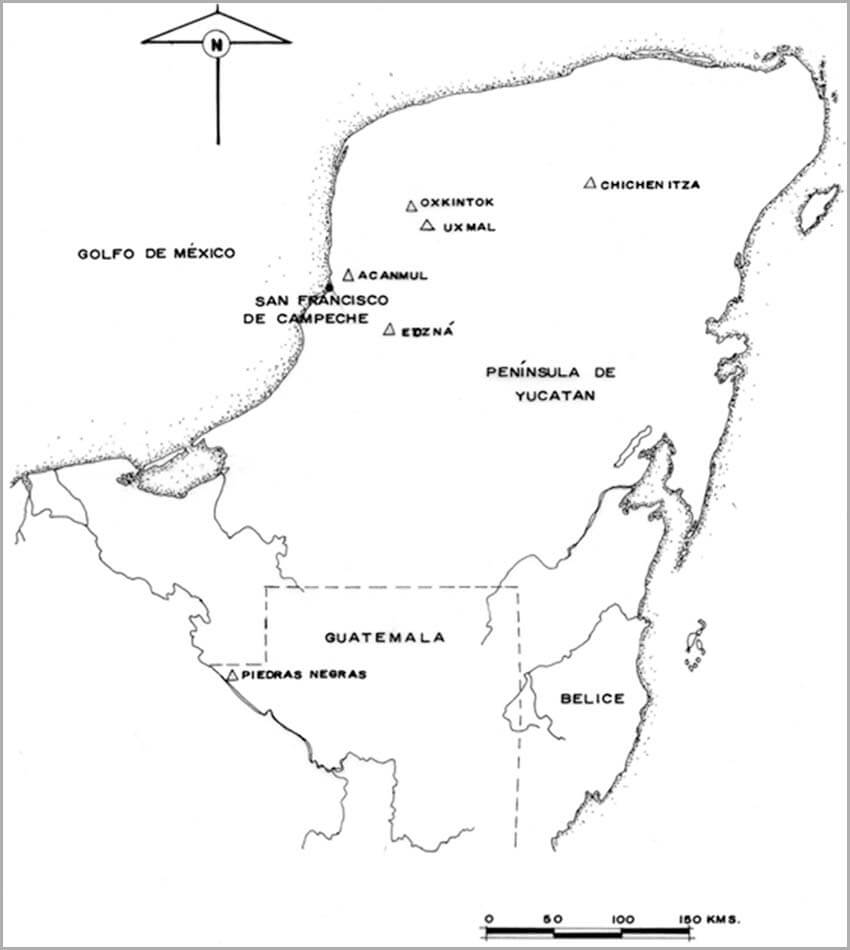

The little-known track Ramírez is following leads to Acanmul, a small, forgotten Mayan ruins located barely 25 kilometers from Campeche city.

The site, which Ramírez discovered through friends, is believed to have been in its prime between A.D. 600 to 800 and has been subject to three sets of investigations by the Autonomous University of Campeche and the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) between 1999 and 2005.

The two-kilometer square ruin has shrunk somewhat; in the 18th and 19th centuries, a large number of the stones were removed for the construction of haciendas at Yaxcab and Nachehá, as is so often the way with remote and unprotected sites.

“Is it looting; of course it is,” Ramírez says. “But I’m not sure where the moral equivalence lies in locals from poor agrarian backgrounds taking materials for construction being criticized by academics who do the same to sell to museums.”

“We live in a time in which everything is seen by its economic potential,” he adds. “And if a site is unregistered, unprotected and not on the tourist trail, well, other things are going to happen here. I’m honestly amazed that Acanmul is still as intact as it is at the moment, truth be told.”

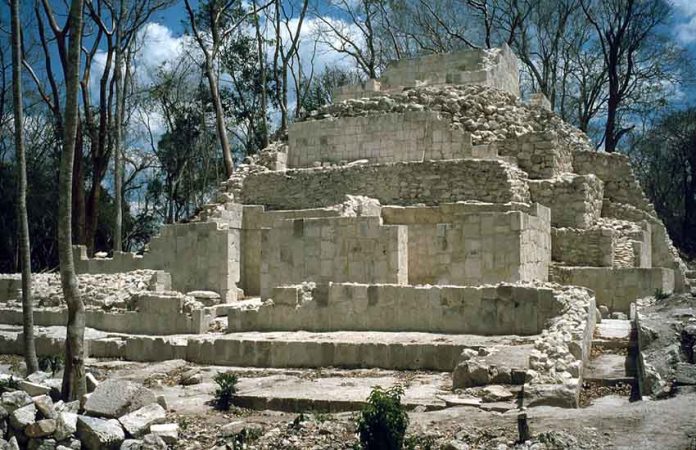

The approach to Acanmul is commanding: like many pyramids built in the Puuc style of Mayan architecture, a number of rectangular concrete blocks comprise a central temple and outlying smaller platforms.

To reach the ceremonial platform at the summit of the highest platform, there is a nearly vertical set of narrow stairs to ascend. In its prime, this platform overlooking a thriving city would have played host to sacred Mayan ceremonies, official gatherings and possibly the occasional ritual sacrifice.

These days, the view from the top is somewhat different: a thicket of large jungle trees obscures the view beyond a handful of meters. The sound of the insects, especially in the falling dusk, seems to envelop everything.

Where once stood a thriving city in the heartland of one of the most ancient civilizations in the world now only exists squadrons of mosquitoes and lizards that skitter across the undergrowth, making Acanmul their home.

These ruins, among many more across Mexico and Central America, are pieces of a giant archaeological puzzle that is the sprawling empire of the ancient Maya peoples, the complete picture of which is still emerging.

It is generally agreed that the Maya settled in the Yucatán Peninsula in 2500 B.C. and that they flourished in the region until as late as A.D. 900, establishing large cities and ceremonial sites at a variety of locations.

As such, ruins in the region today are estimated to number between 2,600 and 2,700 — a tiny fraction of which are open for public access — although new finds emerge on a regular basis.

At the beginning of 2021, for example, INAH’s archaeologists announced that they had found 2,482 structures, 80 burial sites, 60,000 ceramic fragments and 30 complete vessels across the Yucatán Peninsula during excavation for the Maya Train.

Notwithstanding such a monumental cache of recently unearthed heritage, knowledge of Mayan history generally extends only to the most famous archaeological sites: Chichén Itzá, Ek Balam, and Uxmal.

Indeed, Chichén Itzá became one of the New Wonders of the World in 2007, a title bestowed on it by the New 7 Wonders Foundation after a worldwide online poll in which voters chose between nominations ranging from the Eiffel Tower, the Kremlin, Machu Picchu and Stonehenge.

Chichén Itzá has since seen visitors in the millions flock to its pyramids.

As is so often the case, however, tourist-friendly ruins like Chichén Itzá are sanitized versions of their lesser-known cousins and lack the ruggedness of ruins like Acanmul.

Of course, it is impractical to expect the average visitor to bushwhack their way into the depths of the jungle in order to learn about Maya history. Yet, is telling that a few key sites play host to an increasing influx of tourists every year.

This leads to forgetting that the entire peninsula was once a vast civilization and that sites are not so neatly located here or there, signposted by authorities, but almost certainly perpetually beneath our feet.

This packaging of the Mayan world, although convenient for tourism, is damaging to today’s ostracized Maya communities, who are conveniently kept at the margins of social respect and genuine sustainable development even as the sites most venerated by their ancestors are packaged up to compete in popularity contests with the Moulin Rouge in Paris or Times Square in New York City.

The world of the Maya never went away and certainly doesn’t exist at localized points of commerce. It continues to exist in largely disenfranchised communities across the region. It is in the ground under our feet and in the air we breathe.

Understanding that would likely go some way toward a reevaluation of this most unique of civilizations.

It would also work toward the sort of social justice for indigenous peoples that the region so desperately needs.

Shannon Collins is an environment correspondent at Ninth Wave Global, an environmental organization and think tank. She writes from Campeche.