Here, at last, is a place in western Mexico that offers you a chance to commune with Mother Nature yet is not located at the end of a suspension-destroying, washboard brecha (dirt road).

On the contrary, on this journey, you can park your car — no matter its clearance — at the side of a nicely asphalted road and — in just five minutes — cool your feet in the clean and picturesque Ferrería River, located 80 kilometers southwest of Guadalajara and on the way to the little town of Chiquilistlán, Jalisco.

If you happen to be wearing an old pair of tennis shoes or a new pair of Teva sandals, you can wade to the other side of the river — which is less than a foot deep — and follow the trail straight to a rustic, man-made pool filled with the water of a warm spring. If it’s a hot day in May, jump into the deep part of the river for a swim.

Quite possibly, you will find that you have the whole place to yourself.

Continue upstream a bit further and on the riverbank and you’ll see a curious waterfall, which is doubly delightful: it’s great both for drinking and for showering. And if you like the taste of Eau Minérale Perrier, you are in for a treat.

This sparkling water, which I call “Agua Mineral Ferrier,” is not only naturally carbonated but also has a subtle flavor that might just remind you of the Mexican coconut.

Since this river runs all year round, it’s home to all sorts of insects, birds and all sorts of other animals. You can see deer, brightly colored butterflies, kingfishers and hawks, all while enjoying the flute-like song of the melodious clarín, the bird known in English as the Townsend’s solitaire.

Mosquitoes, however, we did not encounter, but do bring your repellent because there are a few pesky jejenes (gnats) in these parts. Also, watch out for poison ivy here and there.

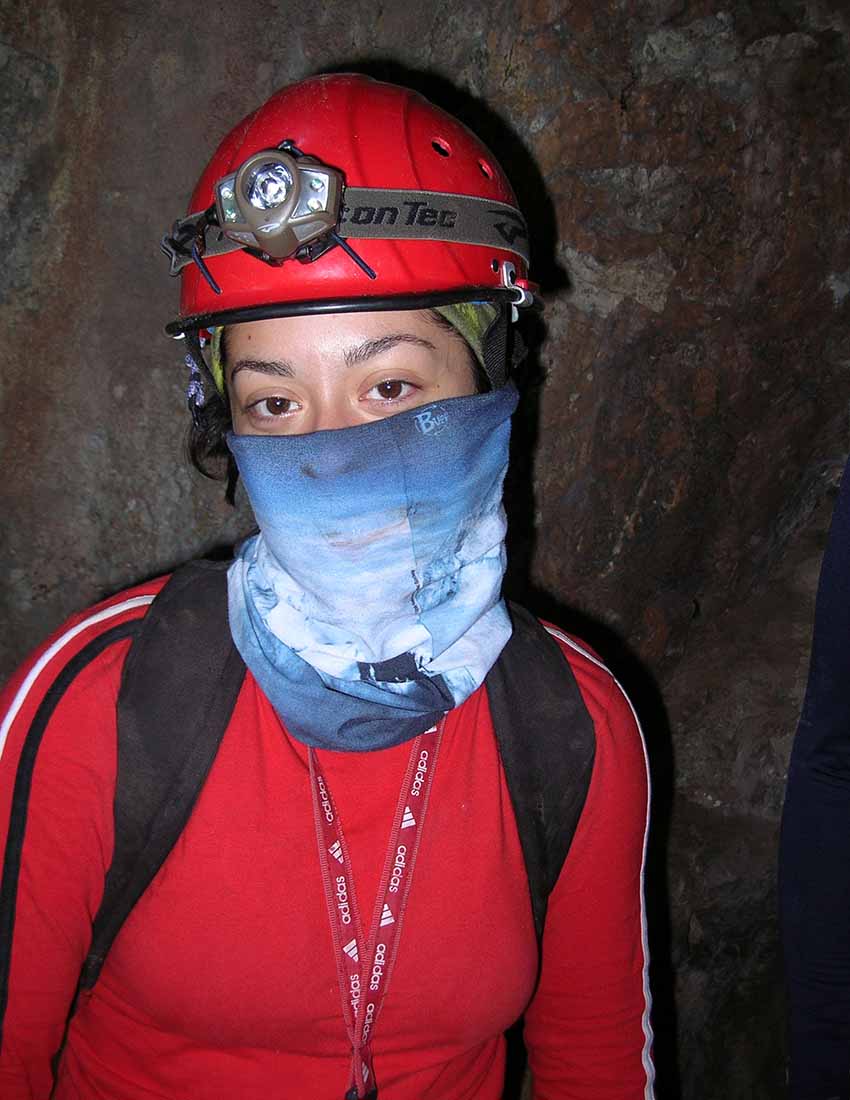

As you walk alongside the Río Ferrería, you will notice occasional holes in the rock wall that look suspiciously like cave entrances. While most of them go back only a few meters, some do open up into genuine caverns deep and complex enough to get you lost.

The reason you find so many holes around here is that the rock through which the Ferrería flows is karst, a kind of limestone especially suitable for cave formation. Put a few drops of dilute hydrochloric acid on a rock in these parts and it will immediately fizz and bubble.

Since ordinary rainwater is just a little bit acidic, it can over thousands of years eat away limestone deep beneath the surface, creating a big empty space, perhaps with a river running through it.

This is how many caves are formed, including two big caves along this stretch of the Ferrería.

One of these is La Cueva de Los Bandoleros, supposedly named after the legendary bandit Don Benito Canales and his gang.

With a name like this, people automatically assume the cave must be full of gold coins and bars of silver, but when we mapped it in 1994, the only treasure we found was bat guano — but not nearly as much of it as fills another cave alongside the Ferrería River.

This one is known as La Cueva de Paso Real and La Cueva de Chiquilistlán, but I prefer to call it La Cueva que no Debes Entrar (the cave you should stay out of) because local people say that more than 30 men died after trying to mine the tons of bat guano found inside it.

While shoveling the bat droppings into bags, they breathed in spores released by a fungus that grows on this guano — and on the guano found in almost every cave in western Mexico.

The spores settle in your lungs, and your immune system reacts to these foreign bodies by encapsulating them, leaving you feverish and coughing — or in some cases dead. This is why I recommend you stick to the river and stay out of the caves.

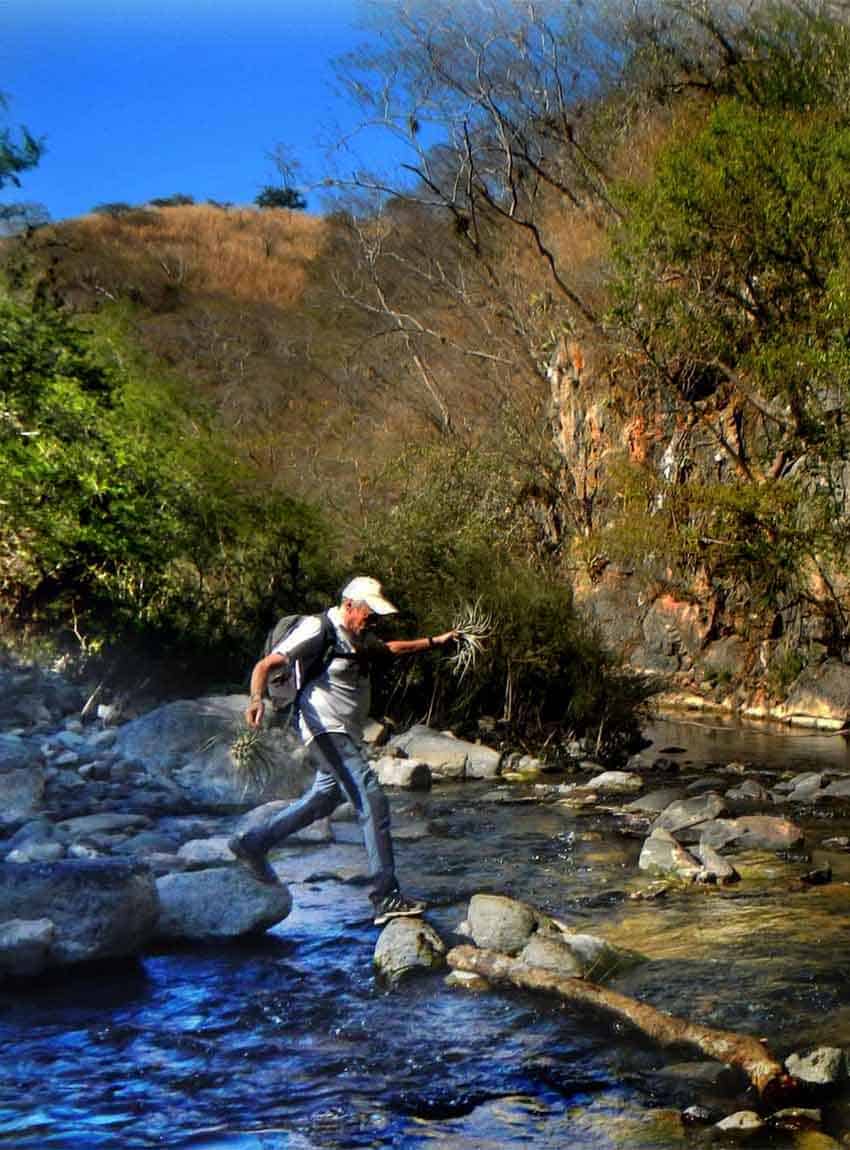

While the Ferrería is very shallow in most places, there is a stretch where it’s deep enough for swimming and especially refreshing during the hot months of the dry season. In the rainy season, however, the river — whose source is a dam 20 kilometers away — can present serious problems, as I discovered one fine summer day when I took two geologist friends for a dip in the thermal pool.

The sky was blue, without a cloud to be seen, as we lowered ourselves into the agua caliente. Five minutes later, I noticed that the river had risen.

It was, in fact, rising so fast that the three of us barely had time to get out of the pool, grab our clothes and run up the side of the riverbank. A few seconds later, the warm pool simply disappeared, completely covered by the now swollen river.

Obviously, it was raining hard somewhere upstream, far, far away.

Fortunately, that was as high as the water got, and after an hour, it began to recede. We then made our way downstream back to the point where we had originally crossed the river. Although the water level had dropped, it was still a raging torrent that looked very capable of sweeping us away.

If we wanted to get back to our car, we would have to cross those frothing, chocolate-colored waters.

“I have a 15-meter length of nylon webbing in my backpack,” I told my companions, whom I will call Mario and María. “Can either of you swim?”

The look of surprise — and perhaps a glimmer of terror — in their eyes told me the answer.

“Okay, I’m going to tie the webbing around my waist. Mario, you hold the other end tight, please. I’m going to walk out to that big rock in the middle of the river, and then you, María, holding onto the rope for dear life, will come over to join me.”

Although María was a tough geologist accustomed to beating her way through the bush with the best of them, this prospect terrified her. “No! no! I can’t do it!” she told me.

“Yes, you can; I know you can,” I replied as I stepped into the churning waters.

And I was right. Once all three of us were at the big rock in the middle of the river, we repeated the procedure. Soon, we were back in the car, changing into dry clothes … and there still was not a raincloud to be seen over the limestone hills above the ever-fascinating Río Ferrería.

To visit the Ferrería River, ask Google Maps to take you to 535R+46M Cítala, Jalisco, where you will find an abandoned house alongside the highway to Chiquilistlán. Next to a locked gate you will see a trail that will take you 150 meters down to the river crossing spot.

On the other side of the river, you will find a trail that leads to the warm pool 300 meters upstream — and 175 meters beyond that, the natural shower. Driving time from Guadalajara: about 90 minutes.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.