Whenever we tire of the dusty bustle of Linares, Nuevo León, my adopted city, my family packs some towels in a bag, slips into flip-flops and escapes to the neighboring town of Hualahuises.

To get there, you take the Old Road to Hualahuises (el viejo camino a Hualahuises). It is a glorious 13-kilometer drive through ejidos (communally owned land), farms and large ranches and past cornfields and acres of orange and grapefruit groves laden with fruit, the blue intensity of the Sierra Madre mountains shimmering before you like a mirage.

I am averse to religion, but as you enter the town, you become aware of an almost transcendental sense of peace and tranquility. With its long, straight, nearly traffic-less streets, Huala (as the locals call it) brings to mind Comala, the ghost town in the classic Mexican novel Pedro Páramo.

Half the population of Hualahuises either lives in the United States or works there seasonally as fruit pickers, mainly in Washington state — hence its nickname “HualaWashington.” Remittances provide a vital stimulus for the local construction industry, and returning families on vacation inject much-needed dollars into the economy.

Lying 118 kilometers southwest of Monterrey, the state capital, this rural town of 7,000 straddling the Hualahuises river was founded by the Spanish colonist Martín de Zavala in 1646 and first populated by small bands of indigenous Borrados and Gualagüises) as well as transplanted Tlaxcalans.

Napoleón Nevarez Pequeño, the town’s official historian, or cronista (chronicler), dubbed the town “the Vatican of Nuevo León” not only because of its particular Catholic character but also because it’s the only municipality in the state surrounded on all sides by another municipality, i.e. Linares.

At the settlement’s founding, the Franciscans brought with them a carved wooden image of St. Christopher, one of three of its kind in Mexico. The locals adopted him as their patron saint.

Believed to be miraculous, the statue is housed in the Temple of St. Christopher downtown and is only removed from the church during religious feast days and processions.

Once, the story goes, when strangers attempted to make off with the statue, it grew so heavy that the astonished interlopers were forced to abandon it in the road. But when some passing farmers came upon it, they lifted it with ease and returned it to its rightful place.

I first visited Huala in December 2001. I was 28 and had just begun dating a young teacher from the school where we both worked.

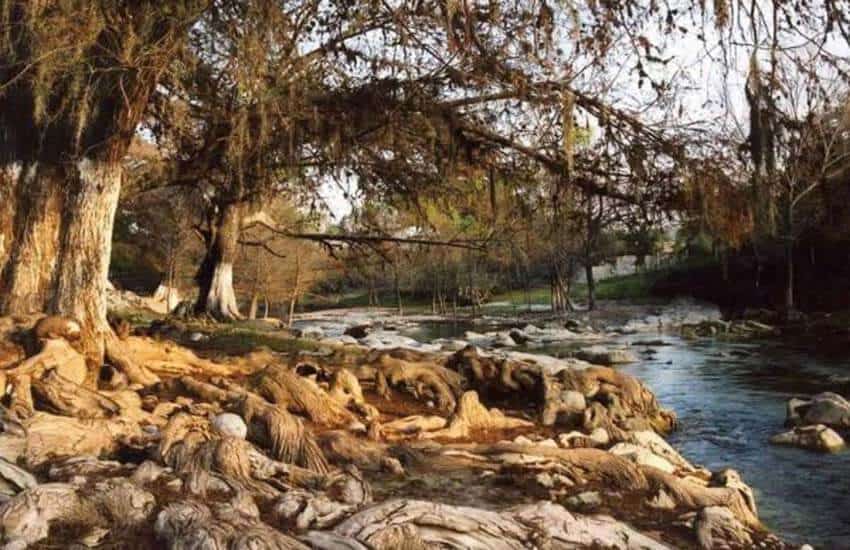

On weekends, Verónica would drive us there in her big old red Chrysler junker, a cassette tape of Huapango music or the Beatles wafting through the open windows. I felt an immediate sense of inner calm and well-being and a reduction in stress and anxiety. I also loved how green everything was, with sabino, oak and fruit trees growing freely.

Twilight here is a rare delight. As evening’s shadows slowly lengthen, people sit outside their homes and sip a furtive Tecate while they talk over the day’s events and gossip with friends and neighbors.

Driving slowly along the silent, dimly illuminated streets, the sizzle of frying chicken or carne asada in back yards mixes with the sounds of conversation and light laughter.

A day-tripper might be tempted to dismiss the place as a sleepy backwater — “a hotbed of rest,” as the late Irish poet and travel writer Kildare Dobbs once sardonically described 1950s Ottawa — but this palpable peace cannot be put down solely to the absence of people. The inhabitants themselves exude an air of inner reserve and calm.

In almost 20 years of visiting Huala, I have never seen anyone here angry or aggressive — or even raising their voice. The people comport themselves with quiet dignity, and when they observe you, it is in a discreet manner, never in a way that causes visitors discomfort.

With my red hair, freckles and pasty white skin, the dogs in the street know I’m an outsider, but no one has once directed at me that coldest of Spanish words: extranjero.

The only commotion I ever witnessed there was when I, my brother and a mutual friend were chased by a red bull while exploring a secluded part of the river. A local woman was shocked to see three gringos, one of them a 6-foot-4 Newfoundlander, running toward her house in a state of barely suppressed panic.

In 2014, the dean of a local university, Ángel Alameda Pedraza, asked me to organize an international literary event with an emphasis on education. El Congreso de Lengua y Literatura (The Congress of Language and Literature) attracted writers from Mexico and around the world. Whenever I could, I would load up the car with authors and sneak them away to Hualahuises for a few hours.

I can still see Canadian poet Bruce Meyer sitting on a rock in his white Stetson safari hat, writing in his journal with a ballpoint pen while a white horse cropped grass on the opposite bank of the river. Bruce would write 29 poems about his experiences in Mexico, which I published in a bilingual edition called “A Linares” (To Linares).

Despite the book’s title, a number of the poems were set in Hualahuises. The white horse — which put Bruce in mind of the one running through the center of the city in Costa-Gavras’ political thriller film Z — features in his poem “Nadar at Río Hualahuises:” (Swimming at the Hualahuises River).

It is common for people from Linares, and even Monterrey, to drive here to sample the town’s excellent cuisine. Tacos Ibarra is famous throughout the region, while Restaurant El Puente is known for its traditional local specialties, including menudo (a thick broth), asado de puerco (pork stew) and guisado de res (beef stew).

My personal favorite is La Parrilla de Gil, a family-run eatery serving delicious tacos (carne asada, trompo, mixtos), hamburgers, tacos piratas and gorditas.

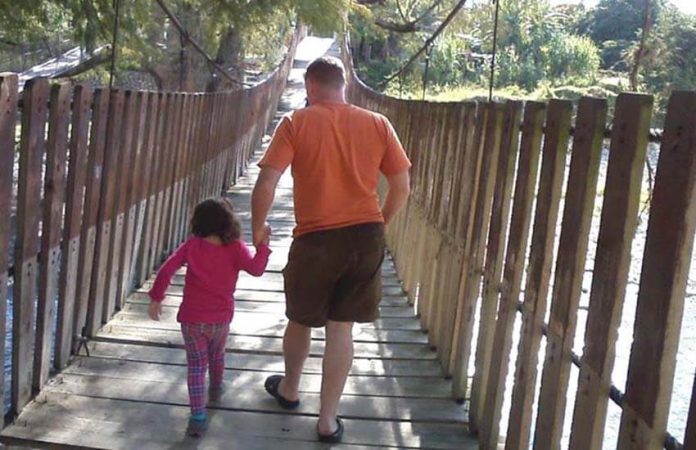

Over the years, our trips to Huala have become more frequent. From the moment I showed Kathleen and Emma how to swim in the clear, cold, shallow waters of the Hualahuises River, they always plead to come back.

That river is part of us now; it runs through our veins.

Upriver from the famous Hanging Bridge (El Puente Colgante), there is a pool (charco, or “puddle,” in the local idiom) beneath the shade of an old sabino festooned with streamers of grey-green moss, where we like to bathe with frogs, darting sprats, and squirrels while entranced by the intermittent “hoo” of a hidden owl or the long ratcheting whine of cicadas on reverb.

Having been raised in Lanesboro, a small rural Irish town on the banks of the majestic River Shannon, I am at home here among these big shady trees, the hearty fare, the charming country people and the laid-back pace of life.

Maybe that’s part of the spell of Hualahuises — maybe I have found my emotional correlative to Lanesboro here? Certainly, watching my daughters splash around and hearing their shrieks of laughter calls to mind my own early days, as to have children is to relive one’s own childhood.

Colin Carberry is a Canadian-born and Irish-raised writer who lives in Los Linares, Nuevo León, with his wife and two daughters. He has published four poetry collections and his work has appeared in publications in North America, Europe and Asia.