The first shots of the Mexican Revolution were fired in Puebla, at the home of the Serdán family, No. 4 Calle Santa Clara, at 7:00am on November 18, 1910.

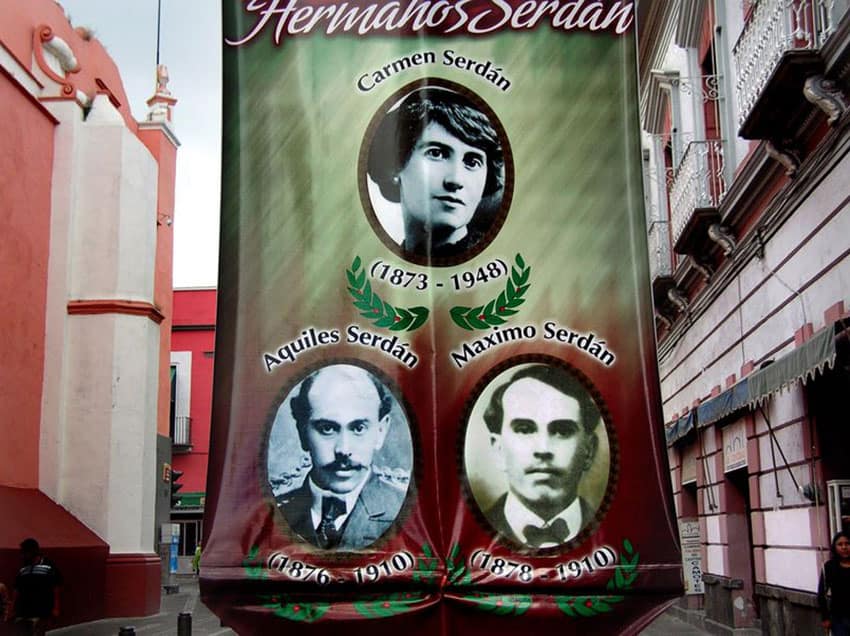

Exactly 100 years after that event, I visited Puebla in hopes that I might learn something about the factors which motivated Aquiles and Máximo Serdán — along with their sister Carmen and 17 sympathizers — to risk their lives in confrontation with the all-powerful government of President Porfirio Díaz.

Naturally, the first thing I did in Puebla on November 18 was walk to the home of the Serdán family, where it all began. Unfortunately, I was not the only person in Puebla with the same idea. As I approached the Serdán home, which is now known as the Museum of the Revolution, I found a huge, impenetrable crowd of people who seemed to be waiting for something.

“The governor is inside,” a policeman told me. “He is rededicating the museum, which has been totally remodeled.”

It was only because of my press card that I got in at all. But at last, there I was, inside the same walls where the Serdáns and their friends had touched off the Mexican Revolution on this same day in 1910.

Just a few months earlier, Aquiles Serdán had been in jail, locked up to keep him from interfering in the seventh “reelection” of Porfirio Díaz. Released on parole, Serdán immediately planned a secret meeting with Francisco Madero as well as with supporters in San Antonio, Texas.

Laughing heartily at the cloak-and-dagger tactics he had to employ, Serdán left home curled up inside a cabinet supposedly full of dishes and cutlery — which was carried to a neighbor’s house. Here he put on a wig and a black mourning veil and headed north disguised as a grieving widow.

In San Luis Potosí he met with Madero, who named him the Puebla revolutionary chief, and plans were made to buy munitions and arms. Six o’clock in the evening of November 20 was chosen as the moment to launch the revolution from Serdan’s home while other groups would liberate the many political prisoners held in numerous jails in the area.

All went well until the evening of the 17th when one of the many guns the Serdáns were stockpiling accidentally went off. A neighbor heard the shot, tipped off the police and the next morning the revolutionaries were fighting for their lives, the brothers firing through the downstairs windows and their sister Carmen shooting from the balcony and shouting to the neighbors, “Come join us! Liberty is worth more than life! Long live non-reelection!”

In short order, most of the new revolutionaries were killed, including Máximo Serdán. Aquiles then shouted up to his sister: “Do you see any military leaders shooting at us?” When she replied no, he said, “What they’ve got out there are country conscripts who have wives, children, mothers and brothers. Since we’ve lost anyway, let’s surrender.”

They decided Aquiles would hide in the basement under a secret trapdoor and slip out at night to reorganize his troops.

This, however, was not to be. Serdán had been badly shot and was feverish. A guard eventually heard him cough and pulled away the carpet covering the trapdoor. “Who are you?” he asked. Aquiles Serdán, delirious, spoke his own name and in return received a hail of bullets. The first stage of the Mexican Revolution had come to an end.

At the museum, I asked an employee who had been working in the place for 32 years what had motivated the Serdáns. She cited their love of country, but when asked whether any personal incident had sparked all this, she recounted the story of Aquiles Serdán’s return from Tehuacán one day, where he had spent many hours with a rich family. Upon his arrival home, Serdán came upon a poor man in front of his door, selling charcoal in an effort to stay alive, and he was greatly moved.

Although this small incident may seem insignificant, it takes on a new light when we dig into the family’s past. Los Serdán, a booklet by Donato Cordero Vázquez, states that when the father of the family, Don Manuel, suddenly died it was discovered that his accountant had been robbing the family for years and as a result, they were destitute.

The family lost their home and ended up living in misery in a very humble dwelling and Aquiles ended up with a job caring for pigs.

It is possible, therefore, that a chance meeting with a poverty-stricken charcoal seller may have brought back to Aquiles Serdán his own bitter experience of being poor in the Mexico of Porfirio Díaz.

Today no one in this country can imagine the atrocious situation of the poor in the early 1900s. According to Puebla en la Revolución, also by Donato Cordero, every year 15,000 poor Mexicans were sold into slavery in the tobacco fields of Valle Nacional, Oaxaca, and 95% of them died during their first seven months of work in what was later called The Valley of Death. Because these people never received pay for their work they were, in fact, slaves.

[soliloquy id="94714"]

Not much better off were the 6,000 Mexicans working in Sonora’s Cananea copper mine, today considered the “cradle” of the Mexican Revolution. Their ridiculously low salaries were paid in vouchers good only in the company store, which featured prices 200 to 300% higher than in nearby towns.

When the Mexican miners dared to go on strike in 1906, they asked, among other things, for an eight-hour working day and “humanitarian treatment.” The owner of the mine, U.S. Senator William C. Green, eventually reacted by recruiting an army of 500 men in Arizona and sending them across the border into Sonora to put down the strike.

Instead of opposing this invasion of Mexican sovereignty, President Porfirio Diaz chipped in 1,200 troops of his own, who helped Green’s men chase the strikers into the hills. The Cananea strike ended with 27 miners dead.

If Mexico’s mestizos were badly treated in those days, far worse was the plight of native peoples who happened to rub Presidente Porfirio Diaz the wrong way. According to Cordero, the Díaz government expropriated 143,000 square kilometers of Mayan land in 1904 to form the state of Quintana Roo, which was turned over to eight politicians for the cultivation of tobacco and timber.

“The Mayans who lived in this area,” says Cordero, “were given two months to vacate their homes because they had no legal titles to the land of their ancestors.”

Even worse was the fate of the Yaqui Indians who, according to John Kenneth Turner, were deported en masse from their fertile lands in Sonora to work as slaves in the sisal fields of Yucatán. This deportation process began in 1905 by presidential decree and the land, houses and cattle of the Yaquis were handed to Diaz’s cronies, the rulers of Sonora.

Turner claims that at least 15,700 Yaquis were transported and forced-marched to Yucatán where — well, what happened deserves to be told in more detail, so watch for the story of the San Marcos train station coming up soon in Mexico News Daily. Suffice it to say that two-thirds of the Yaquis who arrived in Yucatán died during their first year of work in the “Flaming Hell” of the sisal fields.

Poverty in today’s Mexico may be appalling, but it is far better than was the situation of the poor in 1910 when Aquiles Serdán and his brother and sister gave their lives to touch off a revolution, shouting that liberty is worth more than life itself.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.