Steve Wilson is a former museum director who lives in the United States but has a particular interest in Mexican history.

“I have acquired a copy of the journal of an American who traveled across Mexico in the year 1849,” Wilson told me in an email. “As the route he followed took him through Guadalajara, I think you will find his narrative interesting.”

“Interesting” hardly does justice to Wilson’s discovery. The journal was penned by one Benajah Jay Antrim who, it seems, was not only a good writer but also a talented sketch artist.

“In addition,” said Wilson, “I have copies of 115 sketches Antrim made during the journey, all of which he later transformed into watercolors.”

Wilson recently retraced Antrim’s east-to-west route across Mexico, from Tampico to Mazatlán, in order to better understand all the references in the journal. Next, he plans to exhibit these watercolors in both the U.S. and Mexico.

The very first page of B. Jay Antrim’s journal gives us an insight into what sort of person he was. Beguiled by the Gold Rush, he tells us he has decided to quit his profession as a mathematical instrument maker and to travel to California.

Then he casually remarks that he presumes he would be making the trip “by sea, around Cape Horn.” He puts this rather startling proposal of a 17,000-mile boat ride to his friends, who somehow manage to convince him it would be more reasonable (how much more, I’m not sure) to sail to Matamoros, Mexico, travel across the country to Mazatlán and then continue on to California by ship.

This plan is immediately discarded when the would-be adventurers discover that that part of Mexico was, in those days, infested with hordes of warlike and savage Comanche Indians, who were committing outrages and masacreeing [sic] those found in their way, and that the same route was in consequence very dangerous.”

They finally settle on a route beginning in Tampico, located on Mexico’s east coast 380 kilometers north of Veracruz, and passing through San Luis Potosí, Lagos de Moreno, Guadalajara, Tequila, Magdalena and Tepic, to either the port of San Blas or Mazatlán.

Advertising in several papers, Antrim finds 40 men willing to undergo the voyage. They include dentists, merchants, lawyers, pencil makers and a French teacher among others. On February 1, 1849, they set sail from Philadelphia on the Brig Thomas Walters, with “three cheers to the friends and dear bonnie lassies we leave behind.”

Says Antrim, two days later: “Weather clear and cold with a northwest wind, which drove us out the bay in a beautiful and interesting manner with full canvass on a bounding sea.”

That bounding sea produced the adventurers’ first problem which was, of course, seasickness. Apparently there was not a single sailor in the “company.” Continues B. Jay Antrim in the genteel style of the times: “I left an elegant dinner of soup and chicken to contemplate the foaming billows . . . much to the relief of my inexpressible feelings. The dinner table was less patronized by our gents than on the day previous, who were also contemplating the foaming billows with the same inexpressible feelings.”

Once the gents get their sea legs, the narrative becomes more poetic:

“Tuesday, February 13, 1849. The sun rose beautifully in a fleecy cloud of golden hue, and a brisk wind drove us rapidly towards the Bahamia Bar. Here the bottom is composed of white sand with patches of sponge. The color of the water on the bar for about 60 miles is a beautiful sky blue . . . the day has been warm and clear and the sun set among gilded clouds. There is something exquisite, glowing, brilliant and more diversified with brilliant and unapproachable colors accompanying a sunset scene in this southern clime that seldom occurs to those farther north and infinitely above the artist’s pencil.”

At last, on February 22, after a voyage of 20 days, the “Camargo Company” as they called themselves land in Tampico. “We went to the city plaza and examined strange costoms [sic], dress, appearances of things, &c,” says Antrim. The visitors’ first impressions of Tampico and the Mexicans in general are unfavorable, he says, “but in a few days becoming more familiarized with their very singular manners and appearances, we felt more at home.”

Only by reading the complete journal of B. Jay Antrim will you fully appreciate what Mexico, Mexicans and travel were like in 1849. Fortunately, Wilson plans to publish this fascinating account, together with Antrim’s watercolors, in the near future. Below are just a few of Antrim’s comments made during the nearly 2,000-kilometer journey.

Mexicans, says Antrim, dress as differently from Americans as may be found throughout the whole world but, he says, they are “very clean in their dress; in this respect they far surpass the United States.”

Antrim’s account reminds us of how complicated and vexing travel of any sort used to be years ago. His passport, which cost him all of $2 in the U.S., had to be “countersigned by the alcalde of each large town you pass through within 48 hours after your arrival, costing at each place 25 cents, with also a passport to leave the country, a passport to carry arms and a passport to carry any amount of money beyond your expenses.”

Mexican mosquitoes and ticks, he assures us, bear not the slightest resemblance to those in the States. “They are positively the most numerous and most troublesome inhabitants of Mexico. To pick off three or 500 small ticks, as the cost of a venture among the bushes, might seem unreasonable, but such is very possible.”

Armed with “guns, rifles, revolvers, knives, swords &c” to ward off the guerrillas they expected to meet along the way, the company headed west, at night their blankets “spread at random upon the ground in the open air, and a guard of two set, for every two hours of the night.” They bathed only when they came to a river, with eyes open for alligators.

On March 22, constantly on guard for “all shapes of thieves, robbers, guerrillas &c,” the party entered “the splendid and singular city” of San Luis Potosí:

“The morning sun had already arisen upon the domes, towers, and minarets of Potosí as our company entered it from the north. There was so much of the grand and the humble combined, that I could not but remark its resemblance to what I had read of St. Petersburg and Moscow, as described by travelers in Russia.”

In Lagos de Moreno, says Antrim, “there stands one among the most noble and massive sanctuaries of Mexico. It is certainly larger than any church which I have ever seen in the States, and in workmanship, equal to the finest church of New York. It towers above the city like St. Peter’s at Rome. The interior is still more splendid than its exterior; gorgeous displays of wealth in gold and silver leaf are suspended from the far-off ceiling, plasters of great height trimmed with silver leaf rise between and separate very large and brilliant paintings and a high arching dome throws its many color’d lights down upon the rich counter colors of the chief altar and gives to the whole a peculiarly beautiful appearance.

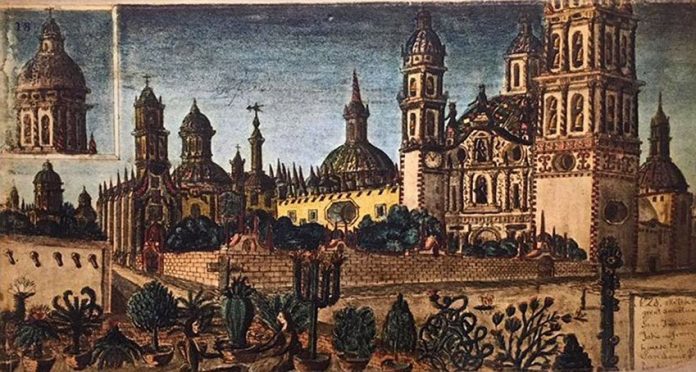

“Bells of great magnitude (originally from Spain) toll at various hours of the day in concert with the other church bells of the city. By permission, I ascended the only tower in which the great bells are suspended, and from that massive stone cupola, I sketched Scene No. 40, looking southwest.”

Jay Antrim particularly liked the city of Guadalajara, whose population he estimated to be “about 175,000, much larger than Baltimore. The city is very regularly laid out in right-angle streets, usually from 20 to 40 feet in width [with] public gardens and several fine plazas, besides market squares variously. It is considered the most beautiful of all the cities of this republic, and second only to the city of Mexico in size. Its communications with other towns is conducted entirely by mules and horses, and all goods carried upon the packsaddles of mules. So that the main roads leading each way from the city are almost constantly crowded for miles beyond the reach of the eye, with thousands of horsemen, and pack mules, going and returning in large companies. Dust is of course very plentiful.”

Most of the subjects of B. Jay’s Guadalajara watercolors were found during Wilson’s retracing of the group’s route, accompanied by his wife Linda, friend Luis Pacheco of Chihuahua, and Dr. Claudia Ramírez Martínez, a history professor at the Autonomous University of San Luis Potosí, who used to live in Guadalajara.

The one they could not find was an exotic stone fountain with water coming out of the heads of four grotesque looking animals, or perhaps the heads of devils. Near the top B. Jay labeled it, “La Pela de los Compathris.” Wilson hopes that a clue to the whereabouts of at least part of the fountain may yet appear.

[soliloquy id="53959"]

Following the “Camargo Company” of 40 members from Philadelphia was special, Wilson explained, because B. Jay not only kept a journal of his adventures, but as a sketch artist managed to graphically capture what he witnessed along the way. “We solved some of the mysteries of his journal and his route, which were not always clear due to his imaginative spelling of Spanish names, such as writing Eastland for Ixtlán,” Wilson commented.

“They spent 44 days after leaving Tampico on March 11, traveling through San Luis Potosí, Lagos de Moreno, Guadalajara, Tepic and finally Mazatlán, covering by their own estimate some 1,200 miles. By the time they reached San Francisco 32 days later on May 25, B. Jay had painted 115 of his sketches.”

Wilson says that some 6,000 Americans crossed Mexico in 1849-50 in their quest to catch a ship on the Pacific Coast, most often Mazatlán, to take them to San Francisco and on to the new gold fields. “As many other Argonauts of ’49,” he adds, “B. Jay found little gold, but soon learned the art of daguerreotyping. As an itinerant photographer, he traveled throughout the Mother Lode country and into the Nevada silver camps. Obviously his Mexican sojourn had given him a taste for travel because we find a daguerreotype of Hawaiian king Kamehameha IV, made by him in 1855. At last, B. Jay Antrim returned home in 1865 and passed away in Philadelphia at the age of 84.

If any reader knows the location of the Lafler Ranch north of Tampico, or what became of the “La Pela” ornate stone fountain in Guadalajara, or would like to host the traveling exhibit of B. Jay’s watercolors of 1849, Steve Wilson may be contacted by email.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.