Tepatitlán is a bustling city located 60 kilometers northeast of Guadalajara in Los Altos de Jalisco (the Jalisco Highlands). Should you happen to be wandering about Tepa — as the locals call it — you might glance up at a street sign and discover you are on Calle Esparza which, in all likelihood, will mean nothing whatsoever to you. But this street, like so many others in Mexico, is named after a citizen who left a mark.

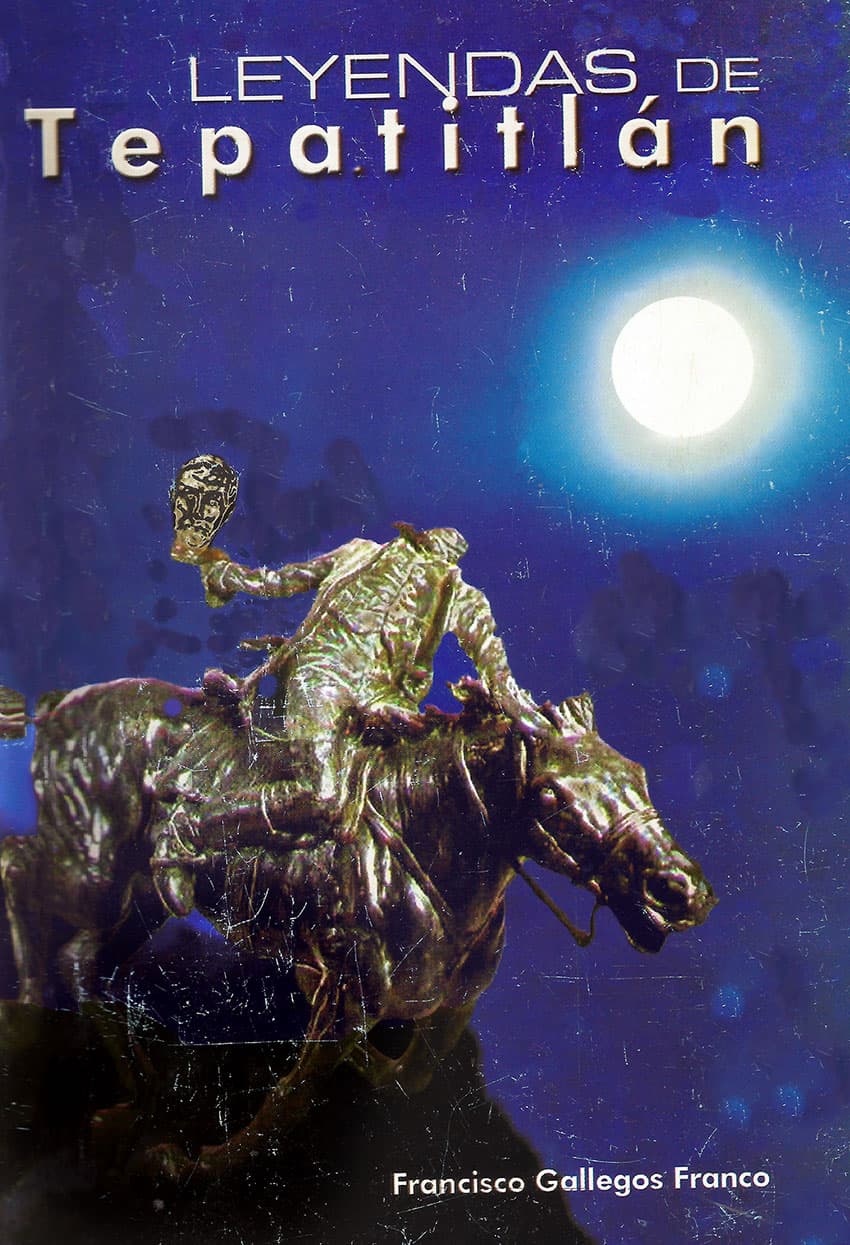

In this case, that distinguished individual is Mariano Esparza, and we know something about him thanks to a little book published in 2006 that is now out of print. The book, Leyendas de Tepatitlán (Tales of Tepatitlán), is by local historian Francisco Gallegos Franco. Once you have read the story of Don Mariano, I doubt you will ever forget him, even if you never stroll down Esparza Street.

Below is my translation of one of Gallegos’s stories, called “If Somebody on this Planet Made It, Then I Can Fix It.”

In 1870, the richest man in Guadalajara was, without a doubt, Don Manuel Escandón, owner of La Escoba Yarn and Fabric Company. In this year, however, a terrible setback had befallen him. The brand new and expensive equipment he had recently imported all the way from Germany was now sitting idle because something had damaged the intricate gear assembly which made the whole thing work. Local engineers had tried to fix it without success, and experts called in from Puebla and Monterrey had thrown up their hands in despair. To make matters worse, it was impossible to find replacement parts, even in the United States.

Don Manuel was nearly out of his mind because it would take up to eight months to get the parts from Germany and, besides, he’d have to buy a whole new assembly, not just the gears that needed replacing. Meanwhile, his 300 employees would be sitting idle while the competition stole all his customers.

Now, right in the middle of this crisis, Don Manuel happened to receive a visit from his friend, Don Lucas González Rubio, a businessman from Tepatitlán. No sooner had he explained his annoying problem than Don Lucas exclaimed, “Hombre, your troubles are over! There’s a man in our parts who can fix your machine in the blink of an eye.”

“¡Caray!” exclaimed Don Manuel, “but I can’t believe anyone in Tepatitlán could … Tell me: is this man an engineer?”

“Engineer? Well, not exactly. The fact is, he barely made it through elementary school. But I tell you, he’s dead smart.”

“Thank you so much, my dear friend, but this machine has a whole new kind of gear train that our best engineers can’t fix. It’s hopeless.”

“Maybe you’re right,” said Don Lucas, “but after all, you have nothing to lose.”

“Whatever you say,” replied Don Manuel politely and promptly forgot the whole thing.

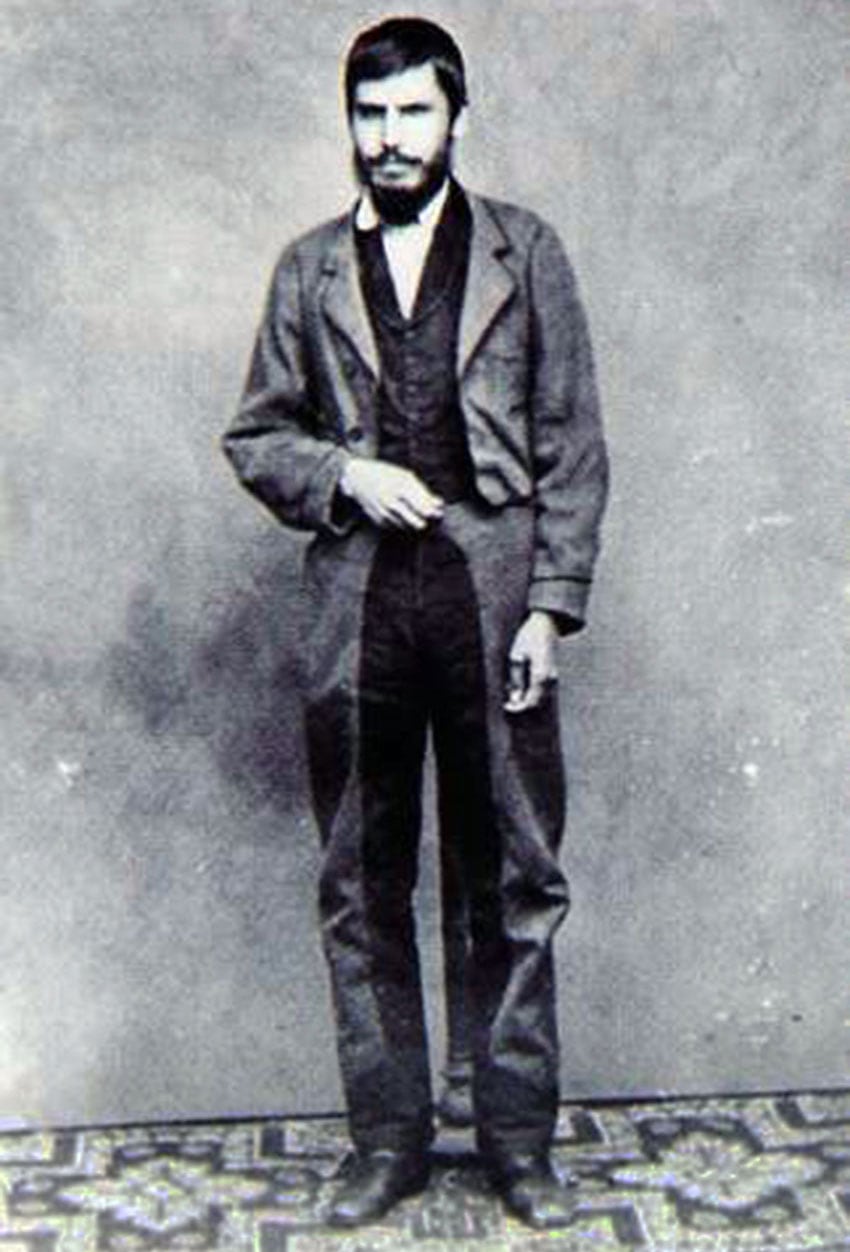

Don Lucas returned to Tepatitlán and told the story to Don Mariano Esparza, whose accomplishments included the construction of the parish clock, which has run continuously for 140 years and is still running today even though some of its cogwheels are made of mesquite wood. It was also rumored that Don Mariano had invented an automatic revolver far superior to the famous Colt but had smashed the prototype to pieces when he realized it would be used to kill people.

Without much difficulty, Don Lucas convinced him to undertake the long trip to Guadalajara, which involved spending two days on horseback. So it was that one week later, Don Lucas reappeared in the sprawling factory, accompanied by a man of humble aspect who wore a poncho and a wide sombrero. Don Lucas was greeted by one and all, whereas his companion barely received a nod and was no doubt taken to be a servant.

Upon seeing Don Manuel Escandón, Don Lucas cried, “Buenos días, my friend! Where’s your machine? There’s not a minute to waste!”

“Machine? Oh, the gear train? Why do you want to see it?” asked the fabric magnate, confused.

“You forgot? I told you I was bringing the man who could fix it,” said Don Lucas.

“What? Who? Where is he?” Escandón asked, looking around.

“Mariano Esparza para servirle,” said a quiet voice from behind the two of them, which meant at your service.

“You?” cried the factory owner. “Let me tell you upfront that I’ve consulted the very best experts and they told me the parts can’t be made here, only in Germany.”

“Germany? Where’s that?” said Don Mariano.

“In Europe, across the sea.”

“To me that sounds like somewhere on this planet, and if that machine was made on this earth, then I can fix it,” Don Mariano said. “Let me give it a try, and we’ll see what happens. Do you have a workshop — with a lathe?”

Escandón nodded and then took the inventor to the German machine. Don Mariano examined the workings with the greatest of care, made meticulous measurements and then shut himself up in the workshop, asking not to be interrupted. For three days, he stayed inside, receiving his meals through a little window. Then he carefully installed the new parts.

The machinery worked with water power, and as they tested Don Mariano’s work, Don Manuel told his foreman to turn the pressure on slowly, expecting to see parts flying across the room at any moment. Don Mariano saw what he was doing and opened the valve full blast.

The gears meshed, and the machine sprang to life … and continued to work for many years thereafter. Words could not describe the factory owner’s joy when he realized what had happened.

“You are a genius, Engineer Mariano!” he shouted. “Tell me what your fee is, and don’t be shy. Whatever you ask, I will pay.”

Don Mariano took out a notebook and mumbled. “Let me see … Don Lucas paid my travel expenses, and you paid my meals … Now, three days work at one peso per day plus … Bueno, that comes to 10 pesos total.”

“You must be kidding, Engineer!” Don Manuel said. “Anyone else would charge hundreds of pesos, maybe thousands! Think again.”

“I have already thought,” the engineer replied. “What you owe me is 10 pesos, exactly what I would have earned in Tepa. So if you’d like to pay me, I’ll be on my way.”

It seemed no human power could change Don Mariano’s mind, and off he went with his modest payment.

Several weeks later, Don Manuel Escandón took a trip to Tepa and handed the man who could fix anything the deed to a house in Tepatitlán. This, Don Mariano could not refuse because he had been specifically told that it was a gift.

As a persona educada, a properly brought up Mexican, he was bound to accept it — and to this day the street where this house was located still bears the name of Don Mariano Esparza.

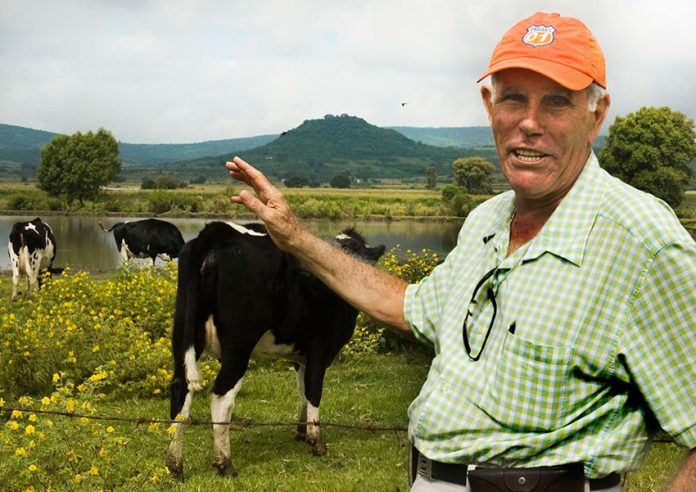

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.