Now, with so much corn here, you would think that Mexico has a long and widespread history of making some kind of alcohol with it. But this is not so.

There are a number of fermented corn drinks such as Oaxaca’s tejate, with little or no alcohol content. Distillation was introduced by the Spanish, but agave and sugar cane became the favored bases for mash since these produce far more fermentable sugars than Mexico’s starch-heavy corn varieties.

The first record of a corn whiskey in Mexico is from the 1920s, when border communities bootlegged into the United States during Prohibition. After alcohol became legal again, distilleries such as DM in Ciudad Juárez eventually went bankrupt.

The practice of making corn whiskey (written as whisky and güisqui in Spanish) would reemerge only in the past decade or so. The drink’s consumption has grown exponentially in Mexico, with sales second only to tequila, even though most brands are expensive imports.

Creating domestic whiskeys not only holds appeal for the pocketbook but also for national pride. If Japan can make world-class whiskeys, couldn’t Mexico? International alcohol producer Reynald Grattagliano absolutely believes it can.

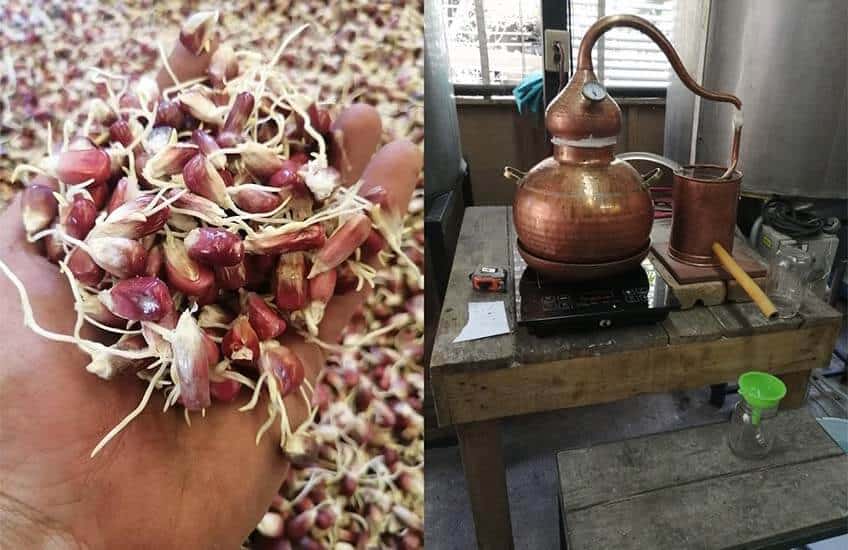

Mexico’s secret weapon is its corn. Mexico has 64 native varieties of corn to experiment with. This not only makes Mexican whiskeys distinct from foreign ones, says Sierra Norte’s Douglas French, it creates a wide variety of distinct flavors.

Chef and food historian Irad Santacruz Arciniega says that it’s not just a matter of genetics but also the different microenvironments that these corn varieties grow in.

Ninety percent of Mexican whiskeys take advantage of the country’s heirloom varieties. Producers such as Hector Justino Gallegos of El Mestizo José Juan Arteaga de Luna of Juan Montaña firmly believe it is necessary to create something authentically Mexican.

Ernesto Vargas and Celeste Mendoza of Cuatro Volcanes go further, saying that producers must have relationships with the communities and cultures of the farmers that provide that grain.

Mexico does not have many legal parameters related to whiskey, but many producers emulate U.S. standards with an eye toward exportation. The grain used must be 80% corn, but some insist on 100%, despite certain difficulties.

For the label añejo (aged), a whiskey needs at least three years in the barrel. Most are reposado with six months to a year. A few are unaged white whiskeys, with the Juan Montaña brand of Aguascalientes even marketing itself as “moonshine.”

Mexico’s whiskey makers have come to the industry via different paths, many diversifying from mezcal production. Others like Tomás Nava of el Gran Tunal has experimented with all kinds of mashes including cactus fruit. Vargas learned whiskey production in the U.S.

The largest and best known of Mexico’s whiskeys is Abasolo, a from the small town of Jilotepec, México state. Its whiskey takes advantage of the local cacahuacintle corn variety, which naturally has enzymes to help convert starches. It is even treated with lime, as if to make tortillas. This whiskey has been internationally ranked and is readily available in Mexico, especially online.

Mexican corn whiskey has caught the attention of major alcohol producers. Revés Distillery was founded by Hans Backoff of the Monte Xanic winery in Baja California. The Koch Group began producing Whisky Prieto and Prieta in 2018. Reynald Grattagliano has established a number of economical whiskey brands in Mexico, most notably Williamson 18. He’s also created the Mexican Whiskey Association.

But most producers remain small, self-financing their efforts, says French, often with a very local or regional distribution area. He began Sierra Norte in the middle of the 2010s because of an agave shortage. Today, he makes five types, each focused on different corn varieties from the Central Valleys of Oaxaca. His main market is foreign, but Sierra Norte whiskeys are available on Amazon and other outlets in Mexico.

One of the major selling points of the Mexican whiskey industry is its socioeconomic benefits for Mexico. The most obvious is that the country has always grown corn, a lot of corn. Grattagiliano sees corn as superior to agave as it is far more sustainable, which requires a lot more fertilizer and takes at least seven years to be usable.

Whiskey provides a new market for the heirloom varieties almost entirely cultivated by small farmers, who cannot compete with corn being imported from abroad. The value added by alcohol production means that whiskey makers can offer better prices to farmers, who then have the ability to preserve more of their traditional corn and lifestyles.

Corn can be grown all over Mexico, but it remains to be seen which varieties hold the most promise.

New brands and distilleries still appear. To date, there are over a dozen producers and even more brands, including Pierde Almas, Maiz Nation and Origen 35 from Oaxaca; Astro from Michoacán; Quinto Legado and Whiskey Lucan from Jalisco; Juan del Campo from Querétaro; and Scar from Sonora in addition to the others mentioned above.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.