“I guess at my age, death is around the corner, but it doesn’t worry me. When it comes, it comes,” said Spanish-Mexican artist Vicente Rojo at an event to honor his 89th birthday. Little did he know he would die only two days later on March 17, 2021.

The Mexican press is rightfully paying homage to this artist’s life and contributions to the country’s culture. He is considered one of the greats among the “Breakaway Generation,” artists that came of age in the 1950s and 1960s, rebelling against the nationalism and political focus of Mexico’s famous muralism movement.

Rojo’s life and art reflect many of the major events of 20th-century Mexico. Rojo was born in 1932 in Barcelona, Spain, to a family opposed to dictator Francisco Franco. When Rojo was 10, his father had to flee to Mexico, one of many Spanish Republicans who did so. Mexico offered asylum due to its own opposition to Franco’s fascism, and in return these Spanish refugees contributed greatly to the country’s literature, arts and publishing.

Rojo followed his father seven years later in 1949, part of a second wave of exiles fleeing repression. He not only managed to find his father on this side of the Atlantic, young Vincente discovered that he had a love and talent for art here as well.

Rojo and his generation succeeded in introducing international artistic trends into Mexico, but it was not easy. Muralists such as David Siqueiros objected that steering away from Mexico’s home-grown artistic movement invited imperialism from the United States. Rojo’s greatest contributions were in graphic arts, working with Mexico’s growing public and private publishing houses, but he was also a sculptor, creating a number of monumental public works.

It could be argued that Rojo’s contributions equal many of the artists of his generation, including José Luis Cuevas, Manuel Felguérez and Gilberto Aceves Navarro, who are far better known. But Rojo was also a designer, and in this capacity, made a contribution that none of these did.

One of the turning points in Mexico’s modern history was the 1985 Mexico City earthquake and its aftermath. The scale of destruction would challenge any government, but the city had made blunders before, during and after that shook the people’s confidence in their government. It is cited as one of the key factors in the eventual downfall of the PRI in 2000. Much of the death and destruction in 1985 was due to poor building codes and the lack of enforcement of the codes that did exist. This was very true for a section of the city dedicated to garment manufacturing just southeast of the main square. Workers here reported early for the day shift, were often shut into factories to prevent theft and worked on floors overcrowded with heavy machinery. This meant that when the 8.1 earthquake struck on September 19, factories collapsed, and many of the dead were the “seamstresses,” poor rural women who had migrated into the city to find work.

In addition, as many as 40,000 of their coworkers found themselves suddenly unemployed with literally no job to go back to. The government was too slow to react, so in the weeks afterwards, grassroots efforts arose to help these women.

One of these was to create a program to make and sell dolls using the sewing skills the women already had.

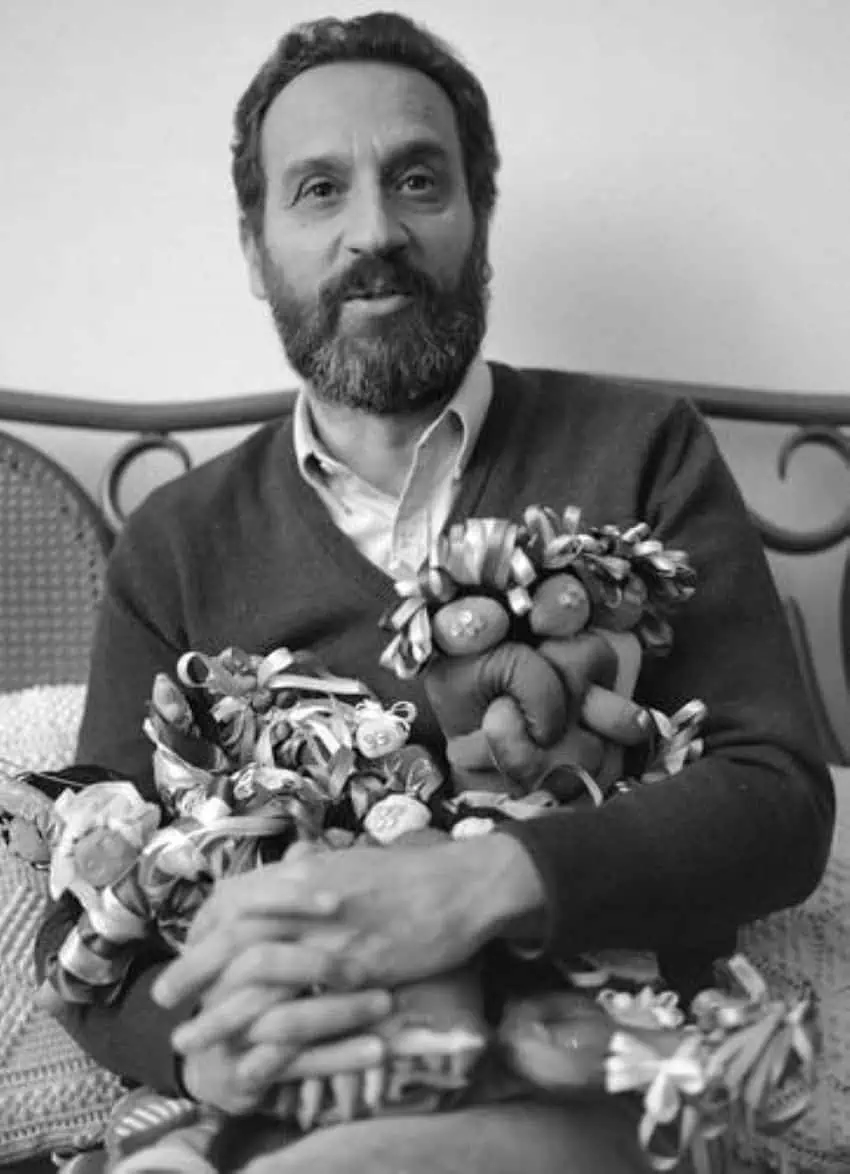

As a designer, Vicente Rojo was central to this effort. Many artists offered to help, but the designs for the dolls needed to be practical — easy and quick to make and easy to sell. After many of the women were organized, Rojo offered six themes for the dolls, on which they voted. The result was to focus on two dolls named Lucha (Struggle) and Victoria (Victory).

Thin, straight-haired Lucha represented the state the women found themselves in. Victory represented overcoming the catastrophe sometime in the future.

Rojo, despite his expertise, worked as a partner, not as a boss. He commented in a 1988 magazine interview that “… it gives me pleasure to collaborate with people who have been hit so hard by life … I made several drawings and let the seamstresses interpret them freely, using their own imagination. Fortunately, I feel this enriched and gave much life to their idea.”

The result was various interpretations of Lucha and Victoria during the years that the project was active. Rojo himself reinterpreted the idea three times. The Lucha and Victoria idea resonated with many sympathizers, drawing in additional support from individuals and institutions.

Rojo also donated an abstract doll design meant to represent multiple seamstresses hugging each other. The doll was made but was misinterpreted as a “donut” or “lifesaver.” In 1987–1988, he also donated a series of designs for cat figures with names like Blue-tailed Cat, Red-hearted Cat and Two-tailed Cat.

The success of the doll program led to an exhibit at one of Mexico City’s avant-garde museums, Carrillo Gill. Named “One called Victoria …” it consisted of 27 dolls by 20 artists working with various seamstresses. The women accepted doing the exhibit because they felt it would bring attention to their continued plight as Mexico City was slowly getting back on its feet. New versions of the exhibit were held annually from 1986 to 1990. There were even exhibitions of the dolls in other parts of Mexico, the U.S. and Europe.

However, by 1990, it was clear that the doll project was winding down as women and the country moved on. The project was never meant to be long term.

A number of Mexico’s newspapers are quoting writer Juan García Ponce (1932–2013) when Rojo would ask him about his health: “Don’t worry, Vicente, we are eternal.” Perhaps part of Rojo’s eternity will be in the memory of the women he helped, along with their descendants.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 17 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture. She publishes a blog called Creative Hands of Mexico and her first book, Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta, was published last year. Her culture blog appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.