When one of Javier Senosiain’s daughters was in kindergarten, she was asked to draw her house. Her picture showed an undulating green roof and semi-buried structure. She left out the giant shark’s head overlooking the garden but even so, the teacher was alarmed enough to call her mother and the school psychologist. The explanation turned out to be simple: her dad’s an architect.

And not just any architect. Senosiain, 73, is Mexico’s leading proponent of so-called “organic architecture,” a concept popularized in the U.S. in the early 20th century by Frank Lloyd Wright, who sought to place his buildings in a harmonious balance with their natural habitat.

The Casa Orgánica (Organic House) drawn by Senosiain’s daughter is not just any house either. Built in a residential neighbourhood in Naucalpan de Juárez just northwest of Mexico City and finished in 1984, it is Bilbo Baggins,’, crossed with the Teletubbies’ Tubbytronic Superdome, meets the modular bubbles of the children’s book Barbapapa. The contrast with the elegant, entirely rectilinear homes all around it could not be sharper.

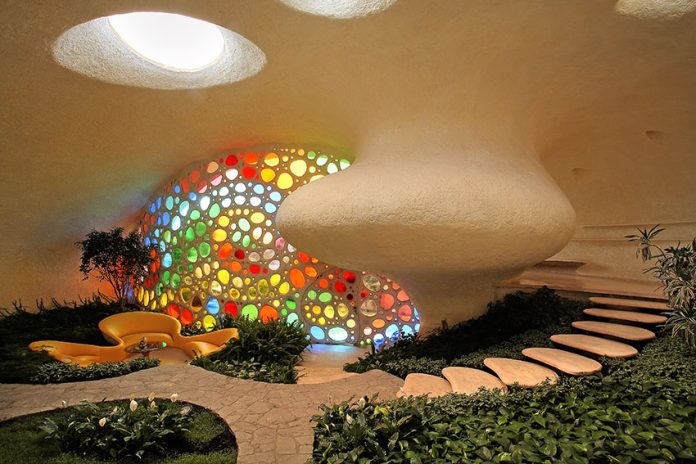

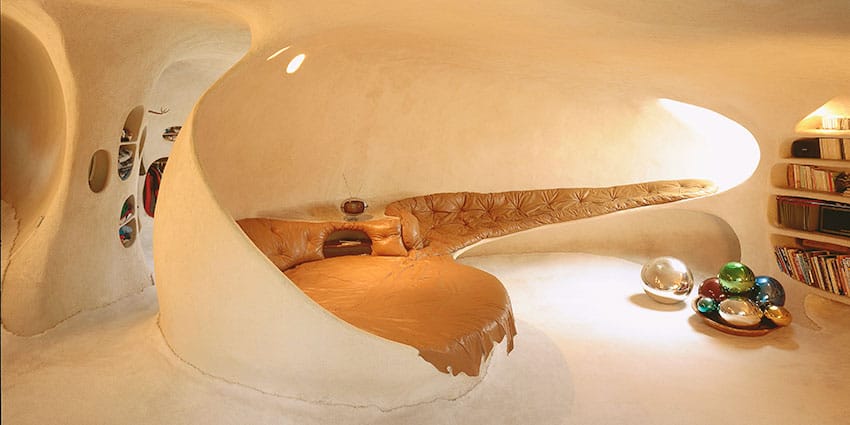

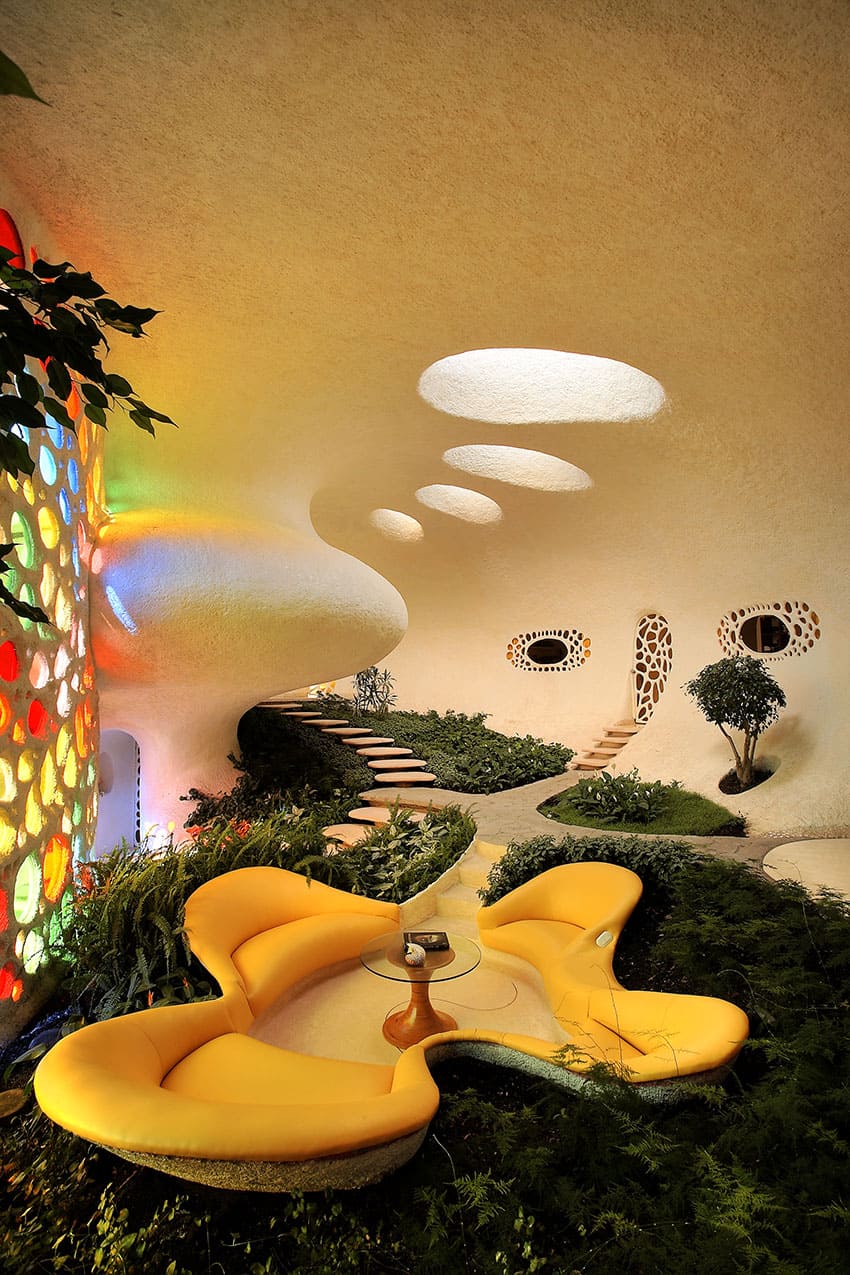

Inspired by caves and igloos, the Casa Orgánica’s tunnels and curves are not only in keeping with nature but a joyful return to life’s origins. Senosiain sees it as the architectural equivalent of a mother’s embrace, or apapacho, a word borrowed from the Aztec language, Náhuatl, meaning “shelter of the soul.”

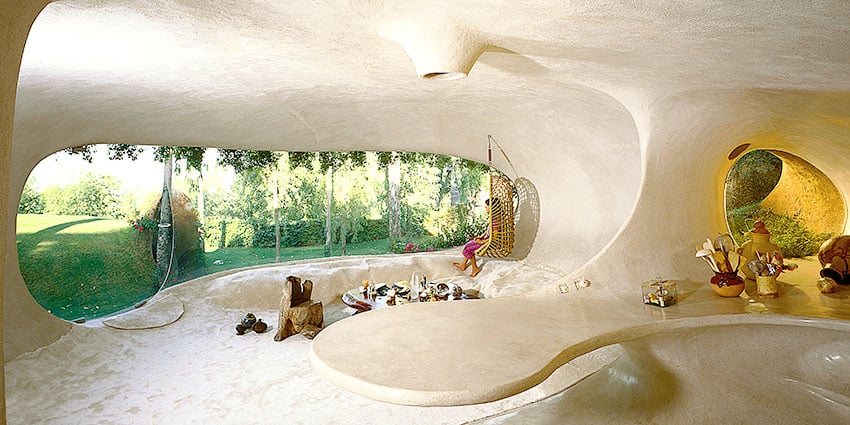

“There are hardly any straight lines in nature,” says Senosiain, who lived in the house for a quarter of a century until his two daughters, now in their 30s, went to university. “Our natural space is curved, it’s the antithesis of the boxes we’re used to.”

He embraced swirls and flow to such an extent that he declared early in his career he would never build straight lines. In fact, he did, but soon threw himself into a glorious evocation of the natural world’s forms, functions and colours. “I’m even more convinced now, with the pandemic, that we’re going to turn to … the origin, what is primitive,” he says on a video call from his Mexico City home, where he is spending the pandemic completing a book.

Next to the Casa Orgánica is the Ballena Mexicana (Mexican whale, completed in 1992) covered in vibrant mosaics. Nautilus (2007), another of his most recognizable works, is reminiscent of a conch shell. The Nido de Quetzalcóatl (Quetzalcóatl’s Nest, 2007) is a horizontal apartment block in the shape of a snake’s body — a nod to the pre-Hispanic plumed serpent deity.

Sam Cochran, features director at Architectural Digest magazine, calls his structures “wildly creative.”

“Senosiain’s work anticipated the interest in biomorphic forms and the innovative merging of indoor and outdoor space that are top-of-mind for many of today’s leading designers,” he says. “It synthesizes many influences into a totally singular point of view.”

To appreciate that in all its glory, you have to take a trip to Naucalpan, a gritty industrial suburb on the northwestern fringe of Mexico City.

The colourful Torres de Satélite (Satellite Towers), designed by famed Mexican architect Luis Barragán and sculptor Mathias Goeritz, rise up from the Periférico ring road. A briefly cheerful respite from the uninspiring fringe of one of the world’s biggest cities, they are Naucalpan’s main claim to fame.

But keep on driving, up to the top of a hill affording panoramic views of the mountains ringing the megalopolis, and you enter another world. Like Antoni Gaudí’s Parc Güell in Barcelona, or Edward James’s surrealist masterpiece Las Pozas in the Mexican town of Xilitla, Senosiain has let his prolific imagination off the leash in the Parque Quetzalcóatl.

Senosiain, who brushes off the notion of retirement but has been forced into a slower pace by the pandemic, began the adventurous — and ambitious — project in 2000, imagining it initially as a conservation project. But it has grown and developed, and he hopes it will finally open to the public within five years.

Once you’re inside the rippling, serpentine walls, manicured lawns give way to secret passageways and a succession of surprises. An ugly electricity substation, and boxy houses sprawling up a distant hill, are sometimes visible — but just as reminders of a prosaic reality that seems light years away from Senosiain’s enthralling, absorbing universe.

Structures of snakes — some studded with marble and tezontle, a reddish-brown volcanic rock; others with intricate mosaic designs picked out in primary colours — slither over the landscape. Sinuous paths bear curved lines picked out in stones, like the ridges of ammonites.

Entering a riotously colourful tunnel that takes its inspiration from a snail feels like being on a magical mystery tour at a funfair: the exit leads into a plant nursery crowned with nearly 2,000 yellow, orange, red and blue panes making up a stained-glass cupola in the pattern of a star. Senosiain’s structures are made from cement slathered on to metal forms covered in chicken wire, a system known as ferrocement. Fountains gush from snakes’ heads into ponds.

Once the park is finished and opened to the public, visitors will be able to recline on white fiberglass chairs floating on the water, whose elegant shapes are reminiscent of doves, or relax on land on tongue-shaped benches.

The park’s meandering spaces take their cue from the natural contours of the land. An abandoned cave will house a shop. A butterfly and hummingbird garden spirals into a vegetable patch that will supply an organic pizzeria and on to an area where a farm is planned.

The magical touch extends to the most mundane of features: a toilet, nestled among the trees, is concealed inside a shiny metal egg. As Senosiain puts it, his designs have to be functional but, equally, “they have to be fun.”

“Young people like the Casa Orgánica more than they did 36 years ago,” he says. “Then, they saw it as something weird. Now they’re much more conscious of ecology.”

Indeed, the Casa Orgánica, near the park, blends into the landscape to such an extent that most of the house is invisible. No walls can be seen, just bubbles for windows, like large, free-form portholes. Instead of a roof, there is a carpet of grass over bulges where the house is hidden below.

That provides not only harmony with nature but also protects the house — erected in malleable ferrocement on top of a sloping skate park-style structure, then sprayed in polyurethane to seal and insulate it — from wet and extreme temperatures that could cause fissures.

Entry is through an oval swinging door and down a cream-carpeted passageway. It feels like descending a flume at a swimming pool as it swooshes round into a surprisingly airy living room illuminated with a large window.

“The idea of passing from a wide space with a lot of light through another that is dimly lit, to re-emerge in another with plenty of light and colour — that’s Barragán’s influence,” Senosiain says.

One of the house’s most dramatic features is the shark’s head that emerges into the garden. It was Senosiain’s upstairs office, its windows affording panoramic views of Mexico City.

Equally inventive is Quetzalcóatl’s Nest, which appears to float inside the park — only 5% of its structure is in contact with the ground. Alongside it is a giant snake’s head studded with hand-painted ceramic rings to evoke the intricate beadwork of Mexico’s indigenous Huichol people. Visitors can experience it for themselves on Airbnb — but there’s a long waiting list.

Senosiain’s work is “a bit off the grid,” says Francisco de la Isla O’Neill, an architecture professor at Mexico City’s National Autonomous University, who briefly had Senosiain as a professor. With the homes’ curved walls, “you can’t just buy furniture [for his houses] in Ikea,” he laughs.

But, he adds, Senosiain’s exuberant embrace of a different aesthetic to imported minimalism showed “the possibility of doing things differently — and that has value … In terms of exploring the possibilities for how we can change our environment, his contribution is very important.”

Covid-19 has forced us to be more introspective as we have curtailed our movements, while also imprinting on us a more profound yearning for, appreciation of, the outside world. “We are all craving a connection to nature and Senosiain’s work certainly espouses just that,” says Cochran.

And that is the legacy Senosiain himself hopes to leave, he says, summing up his architecture as “a concern with returning to our roots so that we can have a better quality of life.”

© 2021 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.