The skin of a whale shark reminds me of a domino I had as a child.

Whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) are the largest living vertebrates, after the baleen whales. Reaching 19 meters in length, these giant fish avoid cold water and thus roam the world’s tropical and subtropical seas.

Some of these ancient migratory fish spend a substantial part of their lives in the Caribbean Sea, where they are particularly fond of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, as sea turtles are.

Whale sharks are as big as their legendary cousins, the now extinct megalodon (Carcharodon megalodon) — a black-eyed white shark equipped with 3-meter-long jaws that patrolled the warm seas of the Neogene era — the second of three divisions of the Cenozoic Era — 28 to 2 million years ago, devouring whales, sea turtles, other sharks, dugongs and any large creature that dared cross its path.

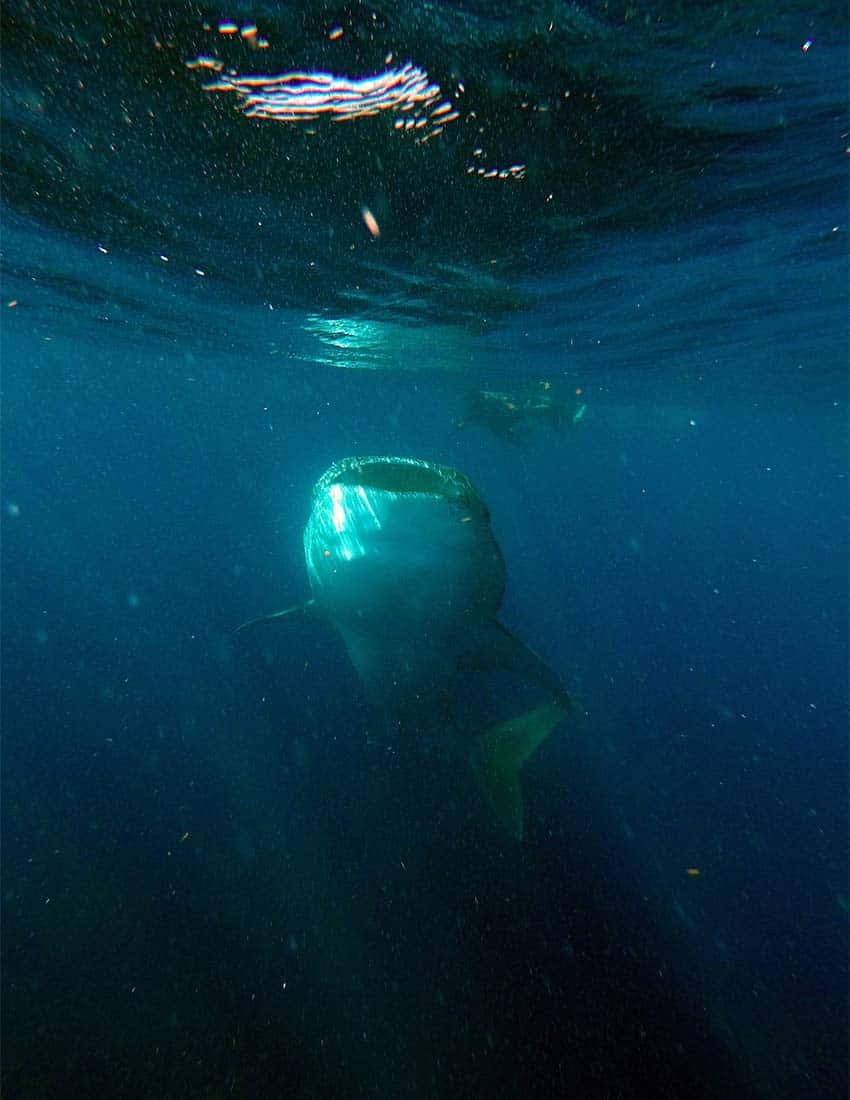

Whale sharks are one of only three species of filter-feeding sharks: they feed by sucking huge amounts of water at high speeds into their mouth — which passes through unique filtering pads in the throat that trap plankton and small fishes — and then spew the “cleaned” water out through their gills.

They capture massive amounts of plankton. Their jaws have more than 3,000 minuscule teeth that they use to macerate the larger bits of food.

The second shark that feeds this way is also the second largest fish (up to 12 meters long), after the whale shark. The basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) is a big-nosed, gentle creature endangered by overfishing to satisfy our insatiable appetite for their meat, skin, and fins.

And the third one is the smallest of the three — up to 5.5 meters long: the megamouth (Megachasma pelagios), a queer-looking, flaccid-bodied, bioluminescent, deep-water shark very rarely seen or captured.

My first face-to-face encounter with a whale shark was 15 years ago near Holbox Island in the Mexican Caribbean; the second was eight years ago in Bahía de La Paz, in the Gulf of California. In both cases, I was swimming with my young daughter.

In Holbox, as we stared intently at its left eye — the size of a headlight on my wife’s car — the whale shark looked back at us as if asking, “Who the hell are you and what are you doing here?”

I saw that wide-open left eye wink at me, even knowing that sharks don’t have eyelashes — an intimate stare down, during which I sensed the mysteries of nature and the strength of an ancient creature longing to live.

A few days ago, I came back from my third close encounter with whale sharks, this time in El Azul, some 20 kilometers off Cancún in the state of Quintana Roo. Here, and in a few other nearby sites, scientists have identified more than 1,000 different whale sharks that seasonally gather to feed in these rich waters.

The world’s largest known aggregation of these sharks — 420 of them in just 18 square kilometers — was found between Contoy and Mujeres Islands, not far from where I was swimming.

This time, being so close to these gentle giants, I couldn’t help but imagine myself gulped down by those huge jaws — like Jonah — and then spewed out with the water through the formidable gills — like Pinocchio — in the process that nourishes the world’s largest fish.

As with nearly all animal species, female whale sharks are more attractive, vigorous, charismatic, enigmatic and elegant than males. They are also larger and longer-lived, travel much farther and carry hundreds of shark pups in their belly.

These sharks are born alive, yet no human being has ever witnessed this natural miracle. In fact, off the shores of the Galapagos Islands is the only place where pregnant whale sharks have been observed with any regularity.

Most whale shark populations across the world are shrinking. They are threatened by overfishing, mainly in Asian seas, where people are still eating their fins, meat and liver.

But they survive despite being frequently struck by boats and despite the changes in water temperature, productivity and marine currents brought about by global warming — and despite some whale shark tourism operators in their habitat who ignore the guidelines that regulate this multimillion-dollar industry.

Every year, from May through September, whale sharks return to El Azul to feed and build their energy reserves. We know a good deal about their lifestyle while they are here, but we don’t know exactly where they go or what they do once they leave El Azul.

However, it is clear that Mexican waters are a whale shark paradise: the Yucatán Peninsula in the Caribbean. In the Pacific, it’s the Gulf of California, the islands of the Revillagigedo Archipelago and the states of Nayarit and Oaxaca.

Scientists working for Pronatura Península de Yucatán — one of Mexico’s most important nongovernmental organizations — have studied whale sharks for a long time. They told me that one of every three sharks that visit El Azul is a female; the rest are males, mainly immature ones.

Unfortunately, I will never know whether the last whale shark I swam with was a female or a male. But I witnessed how she/he swam, rhythmically brandishing its bifurcated tail from right to left and from left to right while its gills slowly opened and closed like an accordion, allowing the warm waters of the Caribbean to flow through them like a melodious salty river.

As I gazed for one last time at the gargantua in the water with me, the whale shark’s colossal body, like a titanic domino, slowly vanished into Mexico’s blue sea, El Azul — a place where, occasionally, souls come to heal.

- In loving memory of Priscilla Pinzón de Vidal (May 10, 1931–June 27, 2022) who taught me to respect and love all living creatures.

Omar Vidal, a scientist, was a university professor in Mexico, is a former senior officer at the UN Environment Program and the former director-general of the World Wildlife Fund-Mexico.