Welcome to the latest edition of My American Dream is in Mexico, an ongoing series spotlighting the growing number of Mexican-Americans and Mexican-born people choosing to build a life south of the U.S. border.

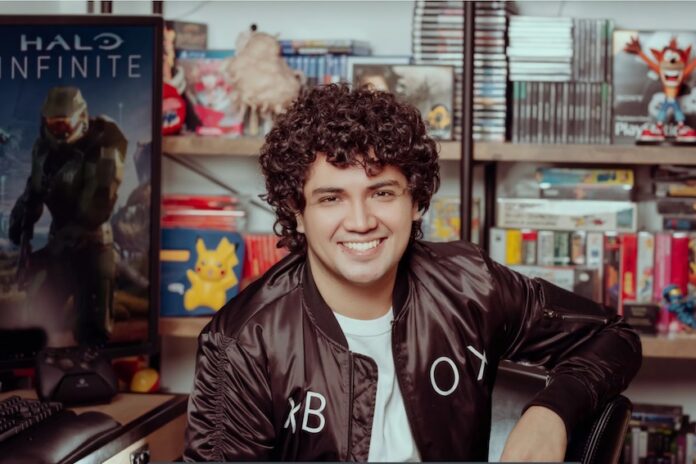

Fernando Reyes grew up in a working-class family in Mexico City, far from the tech campuses and glossy offices that would later define his career. Through talent and tenacity, he carved out a space for himself in the United States, spending nearly a decade working as a game designer for Microsoft. It was a version of the American Dream that many chase and few achieve.

![]()

But then, Fernando did something unexpected: he came home.

Mexico News Daily: You grew up in Mexico City, but your background differed from that of most of your classmates. When did you first become aware of that divide, and what stood out to you?

Fernando Reyes: I wasn’t really aware of the class differences in Mexico until I went to a private high school. That’s when I started to see how different life was for people from wealthier backgrounds compared to mine, my family, my friends, my social circle.

What’s interesting about Mexico City is that people with money have a lot of money. They live very comfortably. And their lifestyle is very distinct, even compared to wealthy people in the U.S.

At the time, I didn’t really think about money or financial struggles—I just assumed everyone lived like we did. Struggling felt normal. It wasn’t until I entered those other spaces that I realized, oh, some people don’t have to worry about these things.

But even then, I didn’t feel envy. It was more like, ‘Okay, they live differently than I do — good for them.’ I wasn’t born into that world, and that’s fine. I just focused on living my own life.

Did your experience navigating privileged and wealthy spaces shape how you see class or identity in Mexico today?

Like most teenagers, I was trying to fit in, but I also didn’t really want to belong in that world. I saw how my classmates talked, how they acted, the kinds of things they were into, and I realized early on that those things didn’t resonate with me. So I made the choice to be friendly, show up, do what I had to do at school — but outside of that, I kept my distance.

Whenever I had the chance, I’d spend time with my old friends or people from other parts of my life. I felt more at ease there, and those relationships always felt more genuine. That’s probably why I was never particularly close with my high school classmates.

That said, it wasn’t like I was excluded or looked down on. The stereotype of the “poor kid” being singled out didn’t apply in my case. I was actually surprised by how respectful and thoughtful many of my classmates were, both in high school and university. Most of them were well-educated and, in many cases, aware of class differences. Sure, there were some spoiled kids, but overall, I was treated as an equal.

Still, the contrast was impossible to ignore. While some of them were planning ski trips or shopping weekends in the U.S., I was just trying to afford the tuition. We could sit in the same classroom and get along just fine, but we were living in very different versions of reality.

You left Mexico in your early 20s to work for Microsoft. What was that like?

The dream was always to make games — ideally, Halo. I wanted to be a game designer, but at the time there weren’t many schools in Mexico focused on that, so I studied computer science to build technical skills and work my way in.

Eventually, I got the opportunity to move to Seattle and join Microsoft as an engineer. I was working on Xbox, not games themselves, but the console. Still, I saw it as my way in. I didn’t expect my first job out of college to be my dream job, so it was crazy that this happened. I was in the right company, around the right people, learning the industry from the inside.

Since high school, I’d always worked on my own games on the side. Even once I started at Microsoft, I kept building things on my own. I was constantly reaching out to people on the Halo team asking, “What do I need to do to get there?” But the answers were all over the place. Some people said it would take 10 to 15 years of experience. There was no clear path.

At some point, I realized I was enjoying my job on Xbox, I liked the team and I was doing well — but I couldn’t stop thinking about that dream of being a game designer. So I told myself: ‘I’ll make one last game, get it out of my system and then I can move on.’

I ended up building a small team within Microsoft, people like me who weren’t working in games but were passionate about them. I couldn’t pay them, but we were all well-paid already, so we did it as a side project, just for fun. The game we made started getting attention internally, and eventually it caught the eye of the Halo team.

One day they reached out and said, “Who’s this crazy Mexican guy making games in his spare time?” They invited me to present the project to their leadership. At the time, I thought that would be the end of the story — a nice way to close the loop. But a few weeks later, they called me back and said, “You’re clearly a game designer. Why aren’t you working with us?”

And that’s how I joined the Halo team.

How did living in the U.S. shift your sense of what it means to be Mexican?

Before moving to the U.S., I didn’t really think of myself in terms of identity. I was just Fernando. I happened to live in Mexico, I happened to be brown, but I didn’t see those things as defining who I was. Being Mexican wasn’t something I consciously carried as part of my identity.

That changed when I moved to the U.S., because suddenly, it was my identity. People there made it clear. In Mexico, almost everyone around you is Mexican, so nationality, race or language rarely come up as points of difference. But in the U.S., those things become visible and, in many cases, central to how people see you.

That shift made me notice all these parts of myself that I hadn’t labeled before: my humor, my food preferences, how I relate to people. These weren’t just “Fernando” things — they were cultural. They were Mexican things. And when I started meeting other Latinos — Puerto Ricans, Colombians — I began to see both the similarities and the unique traits that come from being specifically Mexican, or even more specifically, from Mexico City.

I think it’s something many Mexicans experience after leaving: we become more patriotic. Not in a nationalistic way, but in a deeper, more reflective sense. Living in a place where your culture isn’t the default makes you appreciate it more. I’d always been proud to be Mexican — but after living in the U.S., I finally understood why. And that gave me a much clearer sense of who I am and how my background shapes me.

Things were going well for you in the U.S. What prompted your decision to base yourself in Mexico again?

![]()

After years in the U.S., I hit a point where I really started missing home. Not just my family or friends, but my culture, my language, the everyday feeling of belonging. I’ve seen it happen to others too. Some people reach that fork in the road where they say, ‘Okay, this is my life now,’ and others realize they want to reconnect with where they came from.

I was tired of always speaking English, tired of the food I missed, the cold Seattle winters and especially the isolation. In Mexico, I never thought about the weather or loneliness; people are just naturally more social. I missed things like hosting friends, staying up late, listening to music. It felt like part of me had been muted.

Initially, Playa del Carmen was just a way to escape the winter, but once I was there, I felt something click. The warmth, the rhythm of daily life, the sun on my skin: it reminded me of who I was before. I didn’t just want a vacation anymore. I wanted to live that version of myself more often. Buying a place there started as a seasonal idea, but it slowly became a way to re-root myself in Mexico. I realized I wasn’t just homesick, I was out of sync with myself.

Did you feel like you were two versions of yourself in the U.S. and Mexico?

Definitely. At some point, I realized I had two versions of myself. There was the U.S. version — speaking English, adapting to American workplace culture, behaving a certain way — and then there was the Fernando from Mexico, who greeted people with a kiss on the cheek, stayed up late with friends and felt fully himself.

It became clear that constantly switching between those personas wasn’t sustainable. I didn’t want to keep fragmenting my identity depending on where I was or what language I was speaking. I needed to reconcile those parts and just be one version of myself, whether in English or Spanish.

Living in the U.S. helped me grow. I embraced things I never had access to before and I became a new version of myself in that process. But it wasn’t until I returned to Mexico that I felt all those pieces could finally come together. I’m still both versions, but now they’re integrated. I don’t need to perform; I just get to be.

How has your perspective on Mexican and Mexican-American identities evolved over time?

Now that I’ve lived in the U.S. and met so many Mexican-Americans, I’ve come to see how much we share, and how much we don’t. We often carry the same roots but very different experiences. And that can make conversations about identity complicated, especially between people who’ve only ever lived in Mexico and those who haven’t.

I think it’s important for both sides to be patient with each other. When I was younger, I didn’t think of myself as “Mexican” or “Latino” in the way I do now. That awareness came from living in the U.S., from being categorized, from experiencing things like racism or being treated differently based on where I’m from. It wasn’t theoretical anymore, it was personal.

A lot of people in Mexico may understand racism or identity politics in theory, but it’s not something they’ve had to confront directly. That makes it harder to talk about—and harder to fix. In the U.S., at least there’s more public conversation around it. In Mexico, it’s still hidden or denied in many ways.

So if you’re a Mexican American trying to talk about identity with someone who grew up in Mexico, or vice versa, just know that you’re likely speaking from different lived realities. And that’s okay. We just need more space for conversations like this, and more openness to listen, because the distance between us isn’t as big as it seems.

![]()

You’ve seen Mexico from both the outside and the inside. What hits differently now that you’re back?

That’s probably the most interesting part of all this, coming back and realizing I’ve changed. I’m not the same person I was before I left, and I see that in the small everyday things. I’m no longer fully “Mexican” in the way I used to be, but I’m not American either. I’m somewhere in between.

I’ve adopted behaviors that don’t always align with the culture I returned to. For example, I really value being on time now. In the U.S., that became part of who I am. But here, if a party starts at 7, it really starts at 9, and that drives me a little crazy. It’s something I accepted before, but now I question it.

Living abroad made me more aware of social norms I never used to think about. When you grow up in one place, you treat those norms as absolute truths. But once you’ve lived elsewhere, you realize there are many ways of doing things — and not all of them work for you anymore.

Even something simple like dinner time illustrates that. In Mexico, it might be 8 p.m.; in the U.S., 6 p.m.. Each version affects your social life, your routines, the way you relate to others. So now, I don’t just follow a cultural script by default. I’ve started choosing what feels right for me.

Looking back, do you feel like you’ve come full circle?

In some ways, yes. But it’s less like returning to the same place and more like looping back with a new perspective. I didn’t really get to be an adult in Mexico City. I left right after school, so now I’m hungry to experience the city in this new phase of life: working, building a home, navigating friendships. It’s like a second chance to live here on my own terms.

For a long time, I struggled with the idea of returning. It felt like failure, like I was giving up on something I had set out to prove. But I’ve realized that coming back isn’t a defeat, it’s a return on my own terms. I accomplished what I set out to do in the U.S., and now I get to come home with new tools, new experiences, and a completely different lens.

Being away gave me perspective. It gave me a deeper appreciation for Mexico, for my culture, and for this city. If I had never left, I don’t think I’d enjoy it the way I do now. The food, the energy, the chaos, it all tastes different. It tastes better. And I think that’s because I had to be away to really see it.

What does “the Mexican Dream” mean to you now, after everything you’ve lived through?

I think the American Dream had a big influence on me, and I won’t pretend it didn’t. A lot of what I’ve learned and experienced comes from my time in the U.S. But at the same time, there’s something deeply rooted in Mexican culture that I could never let go of: the idea of home.

For many Mexicans, home isn’t just a place — it’s family, tradition, community. And that’s something I know I’ll always need. I don’t know if I’ll ever move back to Mexico permanently, but I do know that Mexico will always play a central role in my life. I can’t imagine living forever in the U.S. or anywhere else without finding a way to stay connected to home.

So for me, the Mexican Dream isn’t about choosing one place over the other. It’s about accepting that I’ve become someone shaped by both countries and all my travels. And instead of resisting that, I’ve learned to embrace it, to build a life that lets both parts of me exist side by side.

Rocio is based in Mexico City and is the creator of CDMX iykyk, a newsletter designed to keep expats, digital nomads and the Mexican diaspora in the loop. The monthly dispatches feature top news, cultural highlights, upcoming CDMX events & local recommendations. For your dose of must-know news about Mexico, subscribe here.