Folk art and handcrafts, called artesanía in Mexico, are essential parts of this country’s identity. But the question of how to present them can be controversial.

First there is distinguishing them from fine art, a problem worldwide because there is significant overlap between the two concepts, especially for decorative items that are inspired by the local culture (hence the name “folk art” for many pieces).

In Mexico, nationality and ethnicity are important factors in the authenticity of artesanía — that’s not the case for fine art. Foreign artists can and have had successful careers in Mexico, but no matter how authentically a foreigner or outsider might make a piece of artesanía, it generally won’t be accepted as “Mexican” neither by other artisans nor by collectors.

Add to this issues of identity and politics for artesanía created by any of Mexico’s 68 federally-recognized indigenous peoples.

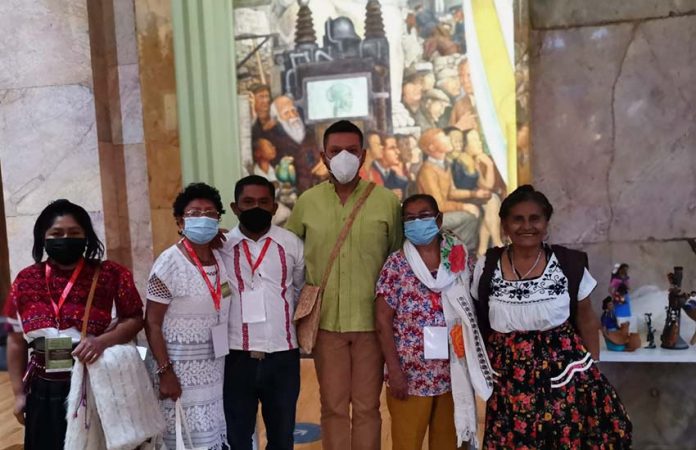

This year, the Mexico City Palace of Fine Arts opened an exhibit on creative expression by Mexico’s indigenous communities called Arte de los pueblos de México, Disrupciones indígenas (The art of Mexico’s peoples, indigenous disruptions). The venue and timing are important.

Why? To start, the building is the most prestigious art venue in Mexico. Also, the event comes 100 years after Mexican muralists such as Robert Montenegro and Dr. Atl promoted artesanía as an integral part of Mexican identity — then a radical idea.

Before then, all artesania was considered to have no cultural or economic value and to be a sign of Mexico’s backwardness.

The Arte de los pueblos exhibit traces the evolution of thought about indigenous peoples and their creative works with a timeline starting just before the Mexican Revolution, then through the promotion of Mexican identity afterward, then to indigenous movements that came later and finally to modern academic thinking about indigenous art.

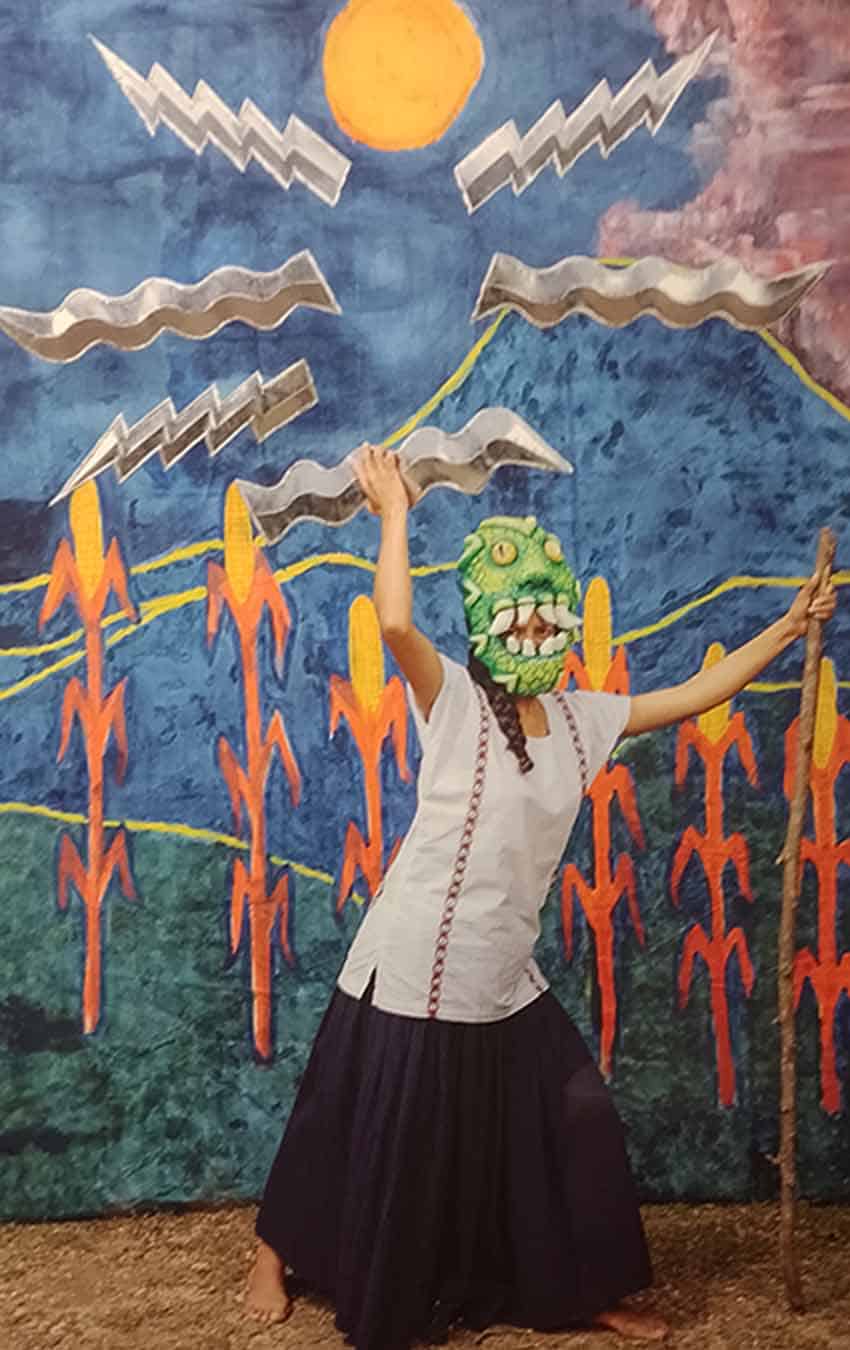

With almost 500 works on loan from 59 different public and private collections, the exhibit’s selections run the gamut from tools and textiles to the “classic” expressions of the visual arts, such as painting and sculpting.

However, instead of stating that all creative works by indigenous hands are equal to that of those nonindigenous, the exhibit has as its premise that using “European” or “Western” artistic or aesthetic concepts to judge indigenous creations is, at the very least, inappropriate.

The exhibition tosses out any dividing line between “artist” and “artisan.” One reason is that there are indigenous cultures that don’t even have words for the “European” concepts of art and aesthetics, says Juan Rafael Coronel Rivera, the exhibit’s principal curator.

So we should instead try to look at the pieces in this exhibit from a different perspective — one that emphasizes such works as “truly” belonging to a culture.

According to Coronel, work that fits this definition is created “inside the culture,” where the objects have cultural value to the community, not just as something to sell. He goes on to say that “… those of mixed heritage [mestizo] do not belong to any specific culture.”

However, given all this, the exhibit’s choice of venue is curious.

Mexico City has the National Museum of Folk Cultures. There is also a prominent Museum of Folk Art only blocks away from the Fine Arts Palace.

The most obvious reason to have it at this location is that the building is quite famous and will attract more visitors. However, the choice of site does seem to reinforce the post-Revolution idea of equating folk art with “real” art to give it the respect it deserves.

Still, that is not really a bad thing. The exhibit has some fine writing at the entrance to each of the halls by Octavio Murillo of the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples that explains the academic concepts, but the notion that “indigenous folk art is art” is what gets people in the door.

I have to admit that I am not comfortable with the idea of lumping all indigenous cultures together like this. Some indigenous groups may not see “art” and “aesthetics” the way we do in the western world, but there have been indigenous cultures that definitely have had “art” in that sense. Just one look at the murals and sculptures produced by the Olmec, Mayan and Mexica attest to that.

But I doubt that sort of thinking just disappeared in 1521.

For centuries, and right up until today, indigenous communities have often had to put their efforts into surviving, so creativity is applied to the making of practical items such as clothing and pottery. With the rise of tourism, it’s also been applied to the making of decorative items for sale. In the end, the equivalence between “fine” and “folk” art, especially in indigenous cultures, remains, but its justification has changed.

This exhibition would have us use only concepts from the indigenous cultures themselves in order to judge the works. But I see two problems with this.

First, it assumes that indigenous people are so very different from the rest of humankind, making their ideas of “art” and “aesthetics” too alien or strange for those who speak Spanish or English. That returns indigenous cultures to the “inscrutable” category, one that relegated distinct, complex cultures to little more than novelties. It also lumps too many cultures with very different languages and histories into some kind of homogenized whole.

To be fair, there are problems with any ideological basis for an exhibition that looks to promote indigenous creative expression as part of Mexico while simultaneously trying to conserve each culture’s uniqueness. There is probably no perfect way to do this.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.