The state of Jalisco hosts the fourth-largest obsidian deposits in the world. In pre-Hispanic times, obsidian was perhaps as valuable as oil is today because from it could be made knives, scrapers and arrowheads, as well as jewelry and mirrors.

Because obsidian was so abundant in western Mexico, a typical mine was nothing more than a hole or trench no deeper than a meter or two and open to the sky.

Today their remains typically resemble shallow depressions, surrounded by the broken bits of tools that didn’t pass muster.

But one day archaeologist Rodrigo Esparza told me about an exception.

“Not far from San Isidro, we found an obsidian mine that’s completely underground and dark as a cave. It’s just the sort of place you would love . . .”

San Isidro Mazatepec is located 13 kilometers west of Guadalajara. Here, members of our Zotz Caving Club found Rodrigo Esparza and Phil Weigand, the legendary discoverer of the Guachimontones, waiting for us next to a beat-up truck.

“This is the first underground obsidian mine we’ve found in Jalisco,” said Weigand, “so it needs to be surveyed and mapped. However, to get inside of it, you have to crawl on your hands and knees through low, narrow passages . . . and we suspect there are plenty of vampire bats inside . . .”

“So you thought of us,” I replied, “but to tell you the truth, it does sound like a place we would love!”

We climbed into the truck bed and the old archaeologist drove us out of town along a dirt road full of ruts. Eventually we passed through a fence on to private land.

“We’ve been riding on an expressway until now,” said Weigand, “but here comes the rough stuff.”

And rough it was. We had to make sure some of us were sitting on two concrete slabs (kept in the truck bed for ballast) so they wouldn’t fly around and land on top of us.

After half an hour of bouncing and bumping, we pulled to a stop among tall oak trees at the base of a small hill. Pieces of obsidian covered every inch of the ground around us like autumn leaves in New England.

Rubbing our sore bottoms after the hammering they had received on the awful, rocky road, we picked up unfinished arrow and spear heads, knives, flakes, scrapers and other fragments that had obviously been worked on and discarded.

We were standing in the middle of a typical obsidian workshop and it brought home the importance — perhaps unimaginable to us moderns — that obsidian played in the lives of the people living here for most of the last 2,000 years.

Those ancients had no metal tools or weapons but they knew what few people today would believe, that nothing on earth is as sharp as an obsidian blade.

“All other liquids crystallize when they turn solid,” explained Phil Weigand, “except obsidian, which has no crystal structure whatsoever.”

Metal can’t be sharpened less than the size of its smallest crystals, but obsidian has no such limit. In the old days, indigenous Mexicans used to line the edges of their flat wooden sword — called the macahuitl — with obsidian flakes, and it is said it could slice off a man’s leg with one blow.

Several pieces we picked up did indeed have a smoky-green luster and a very shiny surface. “Do you think they made mirrors out of this?” I asked.

“Oh no,” replied Phil. “They only used the blackest obsidian for that because they believed mirrors depict how you will look in the afterlife and black was the color of death.”

As we discussed death and obsidian, we walked up the hill to the mine. Emanating from the small, triangular entrance hole, barely large enough for a human being to squeeze through, was a light current of air carrying the unmistakable smell of a dead animal inside.

Immediately, it was decided that I would go first into the Smelly Unknown. I wriggled through the small hole and was received by a welcoming committee of little black flies which angrily flew around my head.

As they didn’t bite, I started crawling along until I found myself in a room where the roof was just one meter above the floor. The evil stench was coming from somewhere in here but I couldn’t find the source.

Above me there was a small skylight. A few meters on, in another room where there was almost no daylight, I nearly put my hand into a gooey black puddle that I immediately recognized from so many visits to western Mexico’s caves.

“Yup, we’ve got vampire bats, alright,” I shouted to the others, who were listening at the entrance hole, hoping this would encourage them to rush right in. Of course, the fresh vampire guano added yet another tantalizing odor to the already notable aroma of the mine.

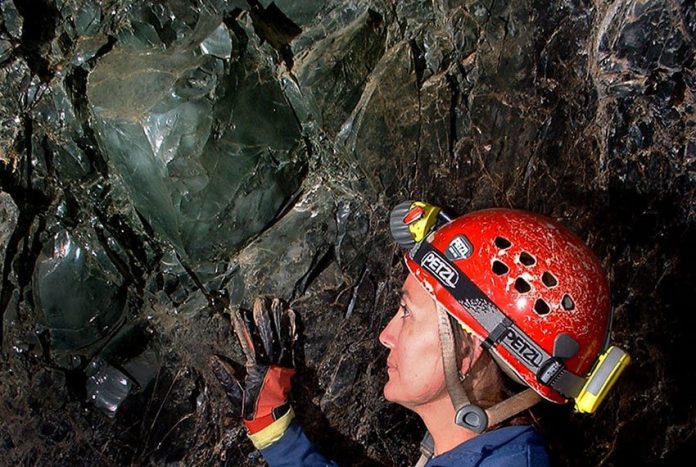

Ten meters from the entrance, I came to a steep down slope. I glanced up at the ceiling and gulped. My headlamp revealed sharply pointed “spears” of obsidian pointing down at me and it looked like any one of them could easily be pulled out — or even fall out by itself — perhaps resulting in the collapse of the entire roof! This was a unique substitute for the stalactites found in limestone caves.

“Amigos, you have to come in here. This is something you’re never going to see in a cave.”

To my surprise, my compañeros (but not the archaeologists, by the way) did come in, braving the bugs, the decomposing corpse and the slimy vampire guano. By then, I was moving down the slope to total darkness and another, much bigger pool of tar-like vampire goo.

Now, they had told us that this mine was as dark as a cave, but I would say “darker than the darkest cave” because the black obsidian ceiling, walls and floor — with a little help from the vampire guano on the floor — absorbed light even more than the black basalt walls of a lava tube, making it exceedingly difficult indeed to see anything using flashlights and headlamps.

The creatures living in that black room, however, had no problem “seeing” us thanks to their marvelous echolocation skills. All around us we could hear them darting.

Suddenly one would land on the wall near us. In the dim light of our headlamps, we could see it shifting left and right, showing us its fangs, shaking its head menacingly and then flying right at us.

Ah, but we knew about this little trick. It’s all a show and they never actually hit you (much less bite you, which they only do to sleeping or immobile prey).

[soliloquy id="78863"]

One nice thing about this room. which we soon christened “The Boudoir of the Vampires,” was that at last we could stand up and move around easily, truly a blessing as we had been crawling along on the natural equivalent of broken beer bottles: shards of volcanic glass that tinkled every time we moved.

In Stygian blackness we walked down the slope to what turned out to be the end of the mine. And suddenly we were standing at the very last spot where the ancient miners had been at work. This was a perfectly vertical wall.

It was flat, except for a beautiful nodule of creamy-green obsidian — big as a basketball — embedded in the wall and protruding from it.

What had stopped the ancient miners from prying out this prize? Was it a shout from a fellow worker: “Hey, Mixtli, forget that rock! Some bizarre creatures are coming down the hill, half men and half animals. We have to get out of here — run for it!”

For whatever reason, they left, their job incomplete. We, instead, were able to complete our survey and then we too, left, allowing the old mine to return to its habitual darkness and silence, broken only by the occasional flapping of vampire wings.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.