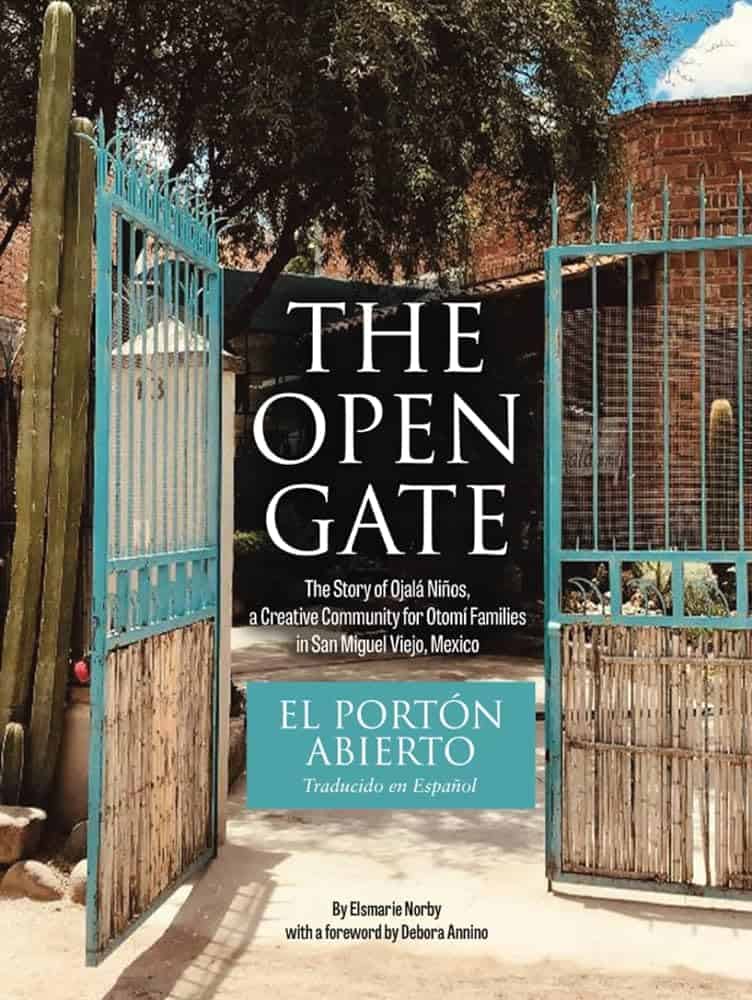

“The Open Gate,” a recently published memoir by Elsmarie Norby, is a heartwarming collection of stories that invites us to learn about the events that led to the creation of the author’s non-profit organization Ojalá Niños, the journey it has been and the people who made it possible. This beautiful coffee table book features some of Elsmarie’s photographs that illustrate her experience.

Born to Swedish immigrant parents in Chicago, Elsmarie Norby grew up feeling like an outsider, struggling to fully embrace American culture and history. As she entered adulthood, she embarked on a quest to find her true place in the world. Little did she know that her passion for music, photography and dedication to social justice would lead her to discover profound meaning in the desert highlands of central Mexico.

While the book briefly touches on her early years, Norby’s main focus is on the stories that unfolded, as she says, “at the other end of my life, when I had the privilege to witness and be a part of the daily realities of the lives of others.”

When Norby was 67 and contemplating retirement, she chose to relocate to a quiet rural village near San Miguel de Allende named San Miguel Viejo, home to Indigenous Otomí people. Enchanted by the place, she purchased a small parcel of land and embarked on the process of building her modest home. This process was marked by meaningful interactions with local workers and residents, enveloping her in what she describes as “a sacred space, blessed by a surrounding aura of kindness.”

She vividly remembers the poverty-stricken landscape of San Miguel Viejo. Most homes were thrown together haphazardly and the roads were all dirt – or, depending on the weather, deep mud. Her new neighbors relied on collecting wood for cooking, using enormous pots over open fires on dirt floors. Internet, cable and landline phone services were non-existent and electricity was intermittent. The community’s water supply came from a 500-year-old well. Despite being only three miles from the city of San Miguel de Allende, the village also lacked basic bus services.

When Norby moved into her new home, local children began a daily routine of passing by her gate on their way home from school. Although extremely shy, they slowed down and peeked in, hoping to get a glimpse of their new strange neighbor.

One day, Norby noticed that the children were carrying paper and chewed-up pencil stubs. That gave her an idea, so she fetched her box of new pencils, sharpened and complete with erasers, and handed one to each child. Every face blossomed into an expression of grateful surprise. How could such a small thing bring so much happiness? Norby was beginning to learn.

Several days later, a group of nine children arrived at her gate. She invited them into her patio, where they all gathered around a table. She gave each child two sheets of plain recycled paper to use with their new pencils and stepped back to watch. Each child became fully engaged, focused and genuinely happy. She realized that all she had given them was a space and two simple materials, yet each child had immediately become creative.

As word spread, more children came to her house to enjoy whatever she had to offer; and volunteers joined to help. She was amazed by the overwhelming joy these children experienced. Norby began to imagine the daily struggle faced by the families in this community just to meet their basic needs of food and shelter, not to mention education.

Noticing that many of the children were undernourished, Norby started providing snacks during music time. As she played a few songs on the keyboard to set the mood, she noticed that a few children were discreetly stashing snacks in their pockets. One of the volunteers, who had a better understanding of the culture, explained that these children were taking food home to share with their siblings or parents. Norby began to comprehend the daily challenges faced by her neighbors.

By the spring of 2008, it became evident that she would be welcoming more neighborhood children to her home for art, music, books and snacks on Wednesday afternoons. “I had responded to some dear children by giving them pencils. Then they led me on to more giving and sharing. I was happy. They were happy. Together we were learning another way.”

The endearing anecdotes she shares in this book convey Norby’s keen powers of observation and insight into the mindset of her neighbors. She was exposing them to a whole new world – from how to make popcorn to the joy found in books and music – and they were teaching her to appreciate the basic things usually taken for granted.

Whenever new materials were introduced, they were treated as valuable treasures that sparked excitement. Children would eagerly reach out to pick up something new and their eyes would light up with ideas. Norby and the volunteers watched in awe as the children created their own space for discovery.

She remembered Albert Einstein’s words: “Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited to all we know and understand, while imagination embraces the entire world, and all there ever will be to know and understand.”

These experiences created the educational philosophy and guiding principles of what came to be named Ojalá Niños with the purpose of providing children of all ages with the opportunity and inspiration to tap into their innate intelligence, ignite their passion for learning and nurture the seeds of self-confidence and expression. Norby states that she didn’t teach her students; she gave them a place to learn.

Norby became welcomed in her neighbors’ homes and invited to baptisms, first communions and quinceañera celebrations. Her skill in photography combined with her love for capturing precious moments earned her the title of the community’s photographer.

When more than 40 children were coming to her house, Norby began writing articles for the local English newspaper in San Miguel de Allende. As her articles attracted donations and more volunteers, she realized it was time to formalize her efforts.

Almost two years after the first group of children gathered in Norby’s patio, a board of directors was formed to apply for official recognition as a non-profit organization. In September 2010, they established a non-profit called Ojalá Niños.

Ojalá Niños continues to be a sanctuary and has benefited over 500 children throughout the years. Elsmarie is grateful for the many kind-hearted individuals who contribute their time and resources to the mission.

The organization offers after-school classes in arts, music and literacy every week. Not all children attend formal schools, but at Ojalá Niños they all have an encouraging haven where they can learn, create, read and discover their talents and interests.

Elsmarie Norby’s journey serves as a powerful example of how one person can make a profound impact by opening their heart and home to those in need.

Sandra is a Mexican writer and translator based in San Miguel de Allende who specializes in mental health and humanitarian aid. She believes in the power of language to foster compassion and understanding across cultures. She can be reached at: sandragancz@gmail.com