The former Hacienda de San Antonio del Potrero is hidden away at the bottom of a huge canyon located just northeast of the town of Tequila, Jalisco. It has been there, they say, since 1785, but you might have a hard time, indeed, to find a single tequileño who has ever heard of it.

This is because the venerable old building is closed to visitors and situated at the edge of a very productive orchard which, of course, is somebody’s private property.

I would never have guessed what secrets that old finca (farm) was hiding if it weren’t for colorful and eccentric botanist Miguel Cházaro who, many years ago, gave me a call:

“John, I’m trying to find a waterfall in a valley near Tequila. Do you want to help me look for it?”

Of course, I said yes, simply because this offer was coming from Professor Cházaro, one of the most outstanding botanists in Jalisco. I knew from previous experience that walking through the woods with Cházaro is like speed-watching the Discovery Channel.

At every step, he points out the most amazing things all around you. But on this particular trip, even Cházaro was dazed by the veritable paradise in which we found ourselves.

We set out one morning on the old highway to Tequila. About six kilometers past Amatitán, we turned off onto a rocky dirt road that wound its way down into La Toma Valley. You definitely need a high-clearance vehicle for this!

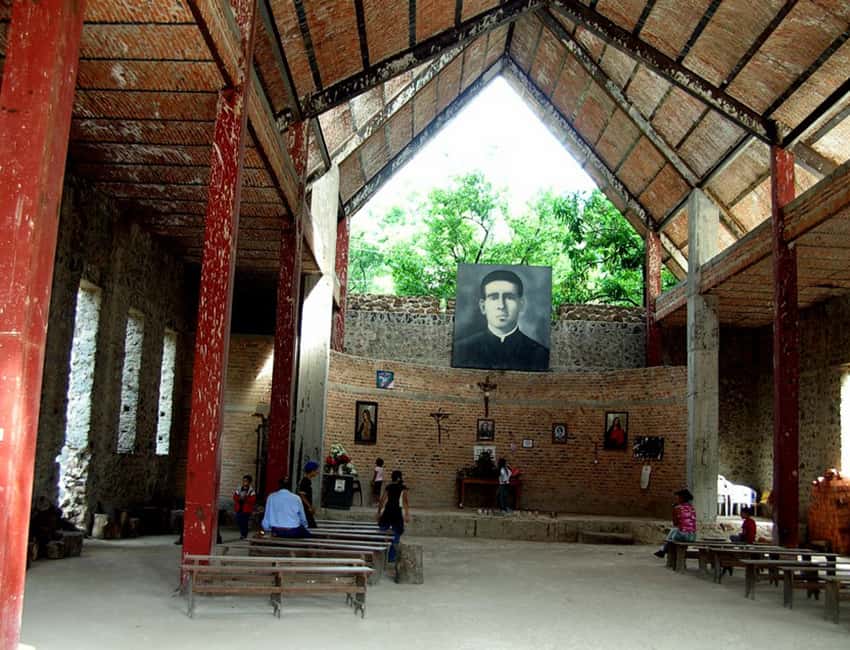

After 17 minutes, we came to the ruins of Hacienda San Antonio, where we met an old-timer carrying two buckets of water. He was Jorge Rivera Landeros, and when we asked him about the history of the place, he told us that this valley was where Padre Toribio, a local martyr, tried to hide back in the days of the Cristeros.

“The government finally caught him and killed him. Then they shot several members of my family — right over there. I was just a little boy, so they didn’t kill me.” The awful story of these events is preserved, we discovered, in a corrido (a kind of epic poem set to music) composed by none other than Don Jorge himself.

I should mention here that Padre Toribio is venerated by huge numbers of people in the highlands of Jalisco where he was born, and there are several grandiose churches erected in his name. In 2000, he was canonized by Pope John Paul II.

Over time, Santo Toribio has become the unofficial patron of Mexican migrants trying to cross the border into the United States, supposedly because he has miraculously appeared to many of them. This is indeed ironic because it is said that Padre Toribio wrote a play in 1920 urging migrants not to go to the States.

Unfortunately, the play (a comedy) was titled “Let’s Go North!”

Maybe that was all his audience remembered.

After hearing the story of Santo Toribio, we asked about the waterfall we were seeking. Don Jorge replied that we’d find it at the end of his orchard, which we were welcome to explore.

“And,” he added, “near the waterfall, there’s a nice pool where you can go for a swim.”

We walked through an arch into what seemed like the Garden of Eden: tall mango, grapefruit, breadnut, mamey, zapote negro, bonete and other exotic fruit trees formed a canopy overhead, and in its shade, we walked alongside (and occasionally through) narrow canals filled with rushing water. Colomos and other humidity-loving plants were growing everywhere, giving no sign whatsoever that this was the dry season.

As we walked, Miguel Cházaro pointed out interesting examples of the local flora, like blue tomatoes.

To me, the most curious plant by far was the bizarre and mysterious cuastecomate or Mexican calabash tree (Crescentia alata), which produces a gorgeous but stinky yellow flower with blood-red veins and a perfectly round green gourd about the size of a large apple.

What’s bizarre is that the flowers and fruits do not hang from the branches but grow directly on the tree trunk, like warts on a witch’s nose. And what’s mysterious is that the gourds must be broken open for the seeds to germinate, but they happen to be as tough as cannonballs.

Most modern animals can’t crack them open to get at their delicious and nutritious contents. It is theorized that in ancient times, this job was done by elephant-like gomphotheres. Since these animals are long extinct, it seems amazing that cuastecomates are still with us.

In no time at all, we arrived at the waterfall, whose beauty we could not really appreciate as we were standing right at the top of it, on the very edge of a steep precipice. There was no easy way down to the bottom … unless you happen to be a canyoneer and would enjoy a rappel down the frothing foam.

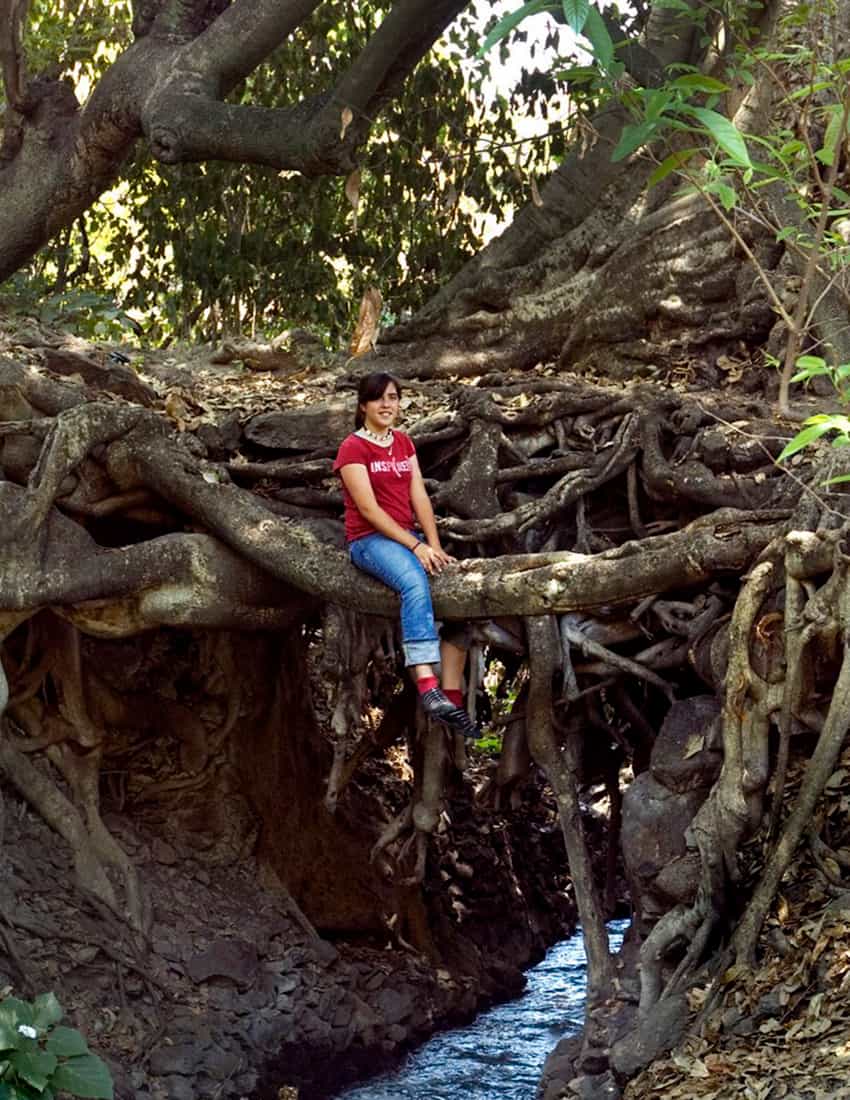

A short walk from the waterfall, the river passes under a bizarre natural bridge made up of the roots of a huge amate, or strangler fig tree (Ficus petiolaris). This is so well camouflaged that the first time we walked over it, we didn’t even notice that we were crossing a river.

Within the clutches of the strangler fig, you can still see the original host tree — long dead, of course — from a mortal embrace.

Only a hundred meters south of the Amate bridge, we came to a small, natural, spring-fed pool about 1.5 meters deep. The water is cool, clean and refreshing and tall shade trees grow all along one side. If there are swimming holes in heaven, they must surely be modeled after this one!

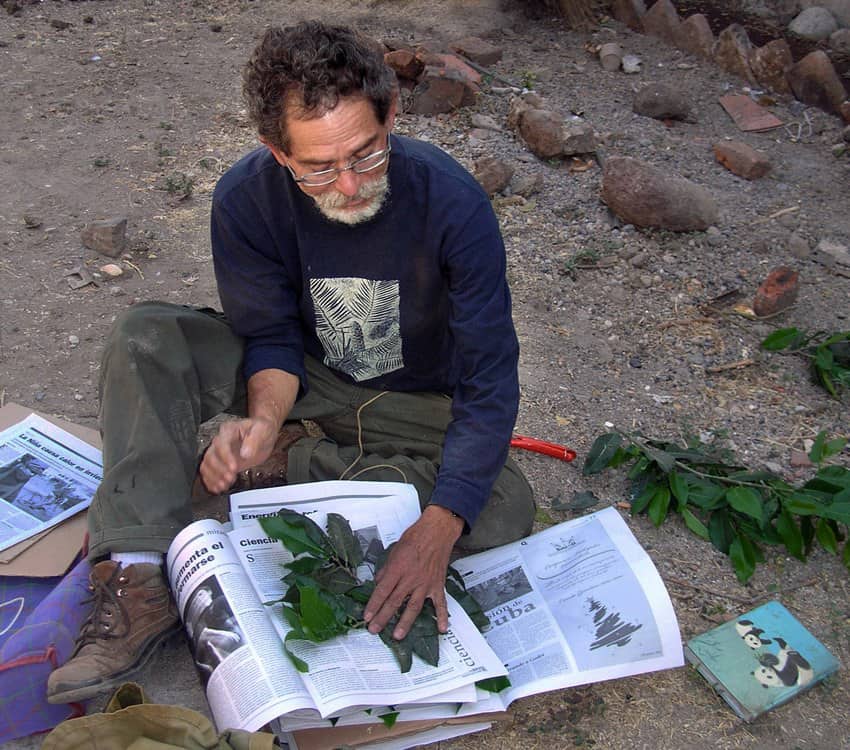

Naturally, Miguel Cházaro was not in the water two minutes before he began discovering all sorts of curious plants growing on the other side of the pool, adding even more specimens for his helpers to press between sheets of newspaper.

Finally, the botanists ran out of newsprint, and we returned to the hacienda where we found Don Jorge busily writing. He handed me a scrap of brown paper torn from a cement bag.

“Sorry, that’s all I could find to write on,” he said.

To my surprise, I found he had written me a poem entitled, “Hola Mister Amigo” that celebrated the arrival of “a brotherly world in which people come together in a spirit of peace and friendship.”

An exotic orchard, a heavenly pool and a heartwarming welcome from a local poet … to total strangers who had shown up on private property unannounced.

It really did feel as though we had stumbled upon the Garden of Eden.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.