On the surface, it is rather curious. By far, most Mexican copper is mined in the state of Sonora, and Mexico mines enough of it to be one of the top 10 sources in the world. But the small town of Santa Clara del Cobre in central Michoacán seems to be the only source of artisanal handcrafted copperware.

Or at least the only source with any kind of real reach.

Copper was once mined here, but those mines gave out long ago. Santa Clara craftsmen today have to rely on buying recycled metal, often from junkyards.

Like most things in Mexico, history explains the present. Copper was known in Mesoamerica and worked much the same as gold and silver. However, the skill needed to work this metal was mostly limited to the Purépecha Empire, the main rival to the Mexica, or Aztecs.

After the conquest, the Spanish took over copper in what is now Michoacán, but their interest in the metal was mostly utilitarian. The most important colonial-era products were cooking utensils, including the iconic cazo, a large open pot/pan combination still used today to cook one of Michoacán’s signature dishes, carnitas (a pork confit).

As central Mexican mines gave out, copper extraction moved northward, but copper working did not. Northern Mexico had and has most of Mexico’s 1 million tons of remaining ore, but this region did not have the history of metalworking that central and southern Mexico had.

That history includes the influence of evangelist Vasco de Quiroga, the first bishop of Michoacán, who was tasked with restoring order in New Spain after a disastrous episode involving the Spanish conquistador and disgraced colonial administrator Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán. Perhaps de Quiroga’s most enduring legacy was creating a town-based system of production and trade in New Spain to give the Purhépecha reason to participate in the new colonial order.

Santa Clara del Cobre received the right to mine and work copper as it was near the mines. Eventually, it provided copper goods not only to all of New Galicia — an autonomous territory of New Spain located in the present-day states of Aguascalientes, Guanajuato, Colima, Jalisco, Nayarit and Zacatecas — but to most of New Spain as well.

Only two things could destroy Santa Clara’s established traditional livelihood: industrialization and the mines giving out. By the early 20th century, local mines ceased to be viable, while factories were producing cheaper pots and pans.

By 1967, copper artisan work was a dying art in Santa Clara: only 36 copper craftsmen remained. What saved it was tourism drawing upon Michoacán’s relatively well-preserved indigenous heritage and the natural beauty of Lake Pátzcuaro attracting visitors.

Tourists created a new market for old goods, as well as a demand for new items based on old techniques and motifs. Today, there are an estimated 800 copper artisans in 86 workshops in Santa Clara. The town is the home of the National Copper Museum and hosts the National Copper Fair each year.

Although the fair has permitted the participation of copper workers from other parts of Mexico since 1981, in comparison, these craftsmen have significant disadvantages in history and experience, reputation and access to markets.

After Santa Clara, the next oldest copper working tradition is found in the tiny towns of Tlahuelompa and Tizapán, both in the state of Hidalgo near the Veracruz border. Local lore states that copper work began here about 150 years ago when an Italian craftsman, name now forgotten, taught locals what he knew.

Their techniques rely on the use of copper already processed into sheets, which attests to their craftsmanship being newer than the copper work in Santa Clara. Although artisans in both of these Hidalgo towns make both common and very fine goods, including church bells, their business is regional as there is no tourism in this highly isolated area.

Any copper work done elsewhere is highly spotty and very recent. Some tourist websites claim that copper is worked in Zacatecas, one place where the metal is indeed mined, but the store at the state’s Casa de Artesanías — government-run exhibition spaces meant to highlight local artisan work — says that it is not done there. It is a similar story for San Luis Potosí.

The only possible exception is Sonora. Copper mining started here in the late 19th century, and it is still big business in the Cananea area. Cananea is far from a tourist attraction, but the copper is now part of Sonora’s identity, and some artisans have picked up working with it.

One very recent example is the work of Édgar Zendejas, who lost his work as a stage designer because of the pandemic and looked for another way to make a living. He found it by twisting copper filigree into very sophisticated designs. In less than two years, his work has been featured in regional newspapers, and he now has clients in Mexico and abroad.

However good the work done in Hidalgo and Sonora might be, many handcraft buyers are looking for an experience as well as something to take home. Its long history, preservation of old techniques and unique environment almost guarantees that Santa Clara del Cobre will remain the center of Mexico’s copper world for many years to come.

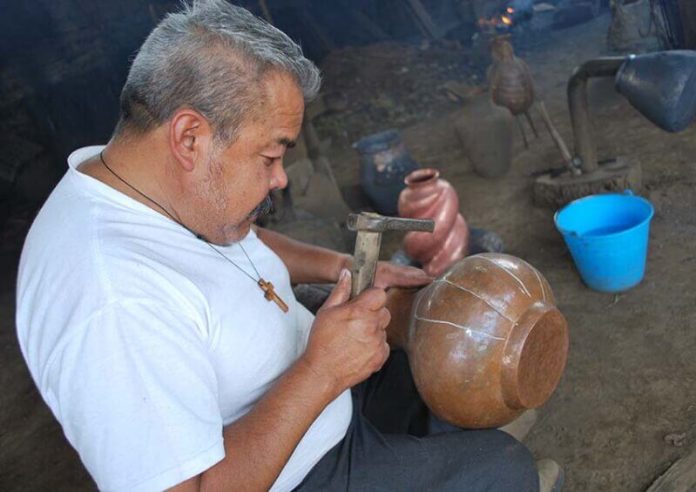

The town is quaint, just 15 minutes away from Pátzcuaro proper. In the center, there is a beautiful wooden church (unusual in Mexico but not for Michoacán) with copper chandeliers and other implements that give it a kind of warmth. Scattered throughout the town are family-owned workshops, often part of the home.

The most traditional of these have generations of knowledge passed down, but the resurgence of the craft means that former farmworkers are changing occupations. Even women are starting to work in the business, which before was purely men’s work.

The link to tourism means that Santa Clara receives state and federal support in training and promotion. There are even courses specifically to train those with no background in copper. But the best work is still done by older craftsmen.

Santa Clara’s reputation in copper is foundational. Not only is it part of the name (del Cobre means “of copper”), efforts to change the name in the last centuries were met with strong cultural resistance. Today, the official municipal name is Salvador Escalante, but no one uses that outside of government records, and I doubt anyone ever will.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.