Arriving in Chiapas’ Selva Lacandona (Lacandon Rainforest) is like arriving at the Garden of Eden, like penetrating a portal that connects the earthly to the divine.

Arriving here is to enter an extravagant, secretive green world where the “cats-and-dogs” rain never stops, to enter a habitat that every year is drenched with 2,000 to 5,000 millimeters of rain that blesses, heals and nourishes the life of the jungle.

Coming here means immersing yourself in an oceanic, infinite jungle rooted in Mexico’s deepest southwest.

In the Lacandon Rainforest, one can fall asleep in the tropics and dream of moist evergreen and montane forests, then awake under a temperate conifer canopy, only to again fall asleep again and awake in a cold montane cloud forest. It all overflows with abundance.

Visiting the Lacandon Rainforest is to become part of a symphony of mysteries, with questions and answers that lay in the Mexican subconscious. It is exploring a paradise of more than 1.5 million hectares of rainforest that welcomes both believers and nonbelievers to their own nirvana.

It is a divine thing, a personal evolutionary moment, an earthly heritage that belongs to the people and the Chiapas municipalities of Las Margaritas, Altamirano, Ocosingo, Palenque, Maravilla Tenejapa, Marqués de Comillas-Zamora Pico de Oro and Benito Juárez.

Visiting the Lacandon is to experience, with enormous national pride, the home of 24% of Mexico’s terrestrial mammal species, 44% of its birds, 13% of its fish, 10% of its reptiles and 40% of its diurnal butterflies.

The diversity of the Lacandon is beyond spectacular. It is simply magnificent.

It is finding yourself among 3,400 species of vascular plants and almost 600 species of trees. It is to fill your mind and soul with the bouquets of mahogany, cedar and rosewood and orchids and bromeliads, while kapoks and other colossal trees stand above like titans, watching everything below.

On its southern border is the Lacantún, a tributary that feeds the Usumacinta River — Mexico’s mightiest, whose name in Nahuatl means “land of little monkeys.” In the Usumacinta, you wade across the same waters that feed the rainforests of the Calakmul and Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserves that unites us with our Guatemalan brothers and sisters.

Arriving in the Lacandon is also coming home to the world’s largest number of bat species. It is visiting the land of the scarlet macaw, the tapir, the jaguar, the crocodile, the catfish and the spider monkey. It is becoming one with the mighty harpy eagle and the river otter, with Mexico’s largest freshwater turtle (Dermatemys mawii), multicolored butterflies and the howler monkey.

With an invitation from biologist and environmentalist Julia Carabias a decade ago, I traveled to the Lacandon for the first time and felt the same anticipation and excitement as when I first arrived, four decades ago, at my beloved Amazonia.

To visit the Lacandon, I traveled first to San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas, then to the Chajul Research Station in the Montes Azules reserve. I stayed at the community eco-lodge Canto de la Selva (Song of the Jungle).

The jungle bewitches, the jungle heals, the jungle educates, the jungle transforms.

Amazonia and the Lacandon are the mothers of all rainforests and home to a myriad of ancestral indigenous peoples and languages. They are home to gazillions of trees and other flora that generously provide us with food, medicine and oxygen. Every day, their forests suck in millions of tons of carbon dioxide that help mitigate global warming, helping humans survive.

Without these two massive rainforests, we all would be in dire straits.

Let’s forget for a moment the fatuous obsession to build mammoth trains that cut through and destroy the Maya rainforest. Because the Lacandon is the real Maya train, the biological corridor that connects and gives life, that freely offers its priceless environmental services, that has provided a home for centuries to indigenous peoples and their ancestral knowledge. All these are divine, evolutionary gifts that we Mexicans still do not appreciate enough.

But arriving in the Lacandon is also to gaze squarely at the contradiction between the divine and the earthly, between the idealized and the real. It is arriving in a region that has already lost two thirds of its rainforests, and today has only 600,000 hectares of well-conserved forests.

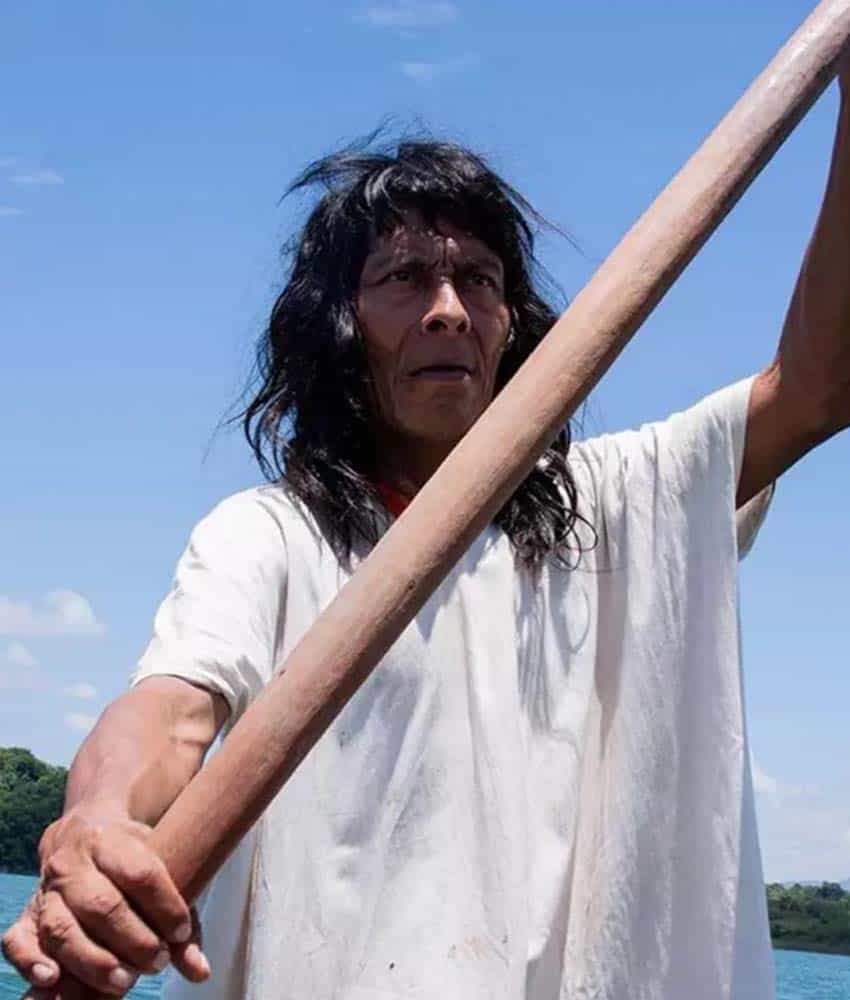

To arrive here is also to emerge in Chiapas, Mexico’s poorest and most forgotten state. This is the land of the Maya Lacandon, the Tzeltal, the K’iche’, the Mam, the Tzotzil, the Chol and other abandoned peoples who have been largely neglected by politicians in turn, decade after decade, regardless of their political party.

In Chiapas, eight of every 10 inhabitants live in poverty. A third of the population suffers extreme poverty.

According to Mexico’s National Council to Assess Social Development Policies (Coneval), Chiapas is the only one of the country’s 32 states where half of the population lacks a monthly income sufficient to cover basic food needs. Arriving in Chiapas is to bear witness to where Mexicans live with disgraceful basic education, infrastructural and health services; a state with millions of our citizen compatriots to whom politicians turn only when they need their votes.

And let’s be honest, if it weren’t for the Zapatista insurrection of January 1, 1994, led by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) and its head, Subcomandante Marcos — an idealist turned into an icon for resistance, that spokesperson with a balaclava —many people today would find it difficult to place Chiapas on Mexico’s map.

This is why, dear reader, I urge you to rush to the Lacandon Rainforest. Dare to glide into this Mexican, Latin American and universal paradise.

Get inside, but with respect for the protected areas of Bonampak and Yaxchilán, of Chan-Kin, Metzabok and Nahá, of the Sierra la Cojolita community reserve and the Montes Azules and Lacan-Tún biosphere reserves.

Because, one not-too-distant day in the future, these might be the last strongholds where your children and grandchildren will be able to rejoice at the magnificent Selva Lacandona, our Maya mother rainforest.

If you care to know more about the Lacandon and the conservation efforts that have lasted more than 30 year, I suggest you visit Natura Mexicana or National Geographic’s Welcome to the Jungle: Exploring Mexico’s Lacandón.

- This article is dedicated to Julia Carabias, with admiration and solidarity, for her more than three-decade long fight to protect the Lacandon Rainforest

Omar Vidal, a scientist, was a university professor in Mexico, is a former senior officer at the UN Environment Program and the former director-general of the World Wildlife Fund-Mexico.