A molcajete is a round mortar made of volcanic rock, used for mashing chile peppers, tomatoes and other ingredients for making salsas. You’ll find them in every market in Mexico and also in every museum, proving that they have been around for a very long time and are still useful.

When I asked people in Guadalajara where molcajetes are made, I either got a blank stare or was told, “They come from San Lucas.”

This is what brought me to a quiet plaza in the little town of San Lucas Evangelista, located on the shore of Lake Cajititlán, about 20 kilometers south of Guadalajara.

Seeing no signs related to mortar making, we walked up to a house at random and knocked on the door. When we told the lady of the house we were interested in molcajetes, a bright smile lit her face and she immediately ushered us inside. Here we met her son, Victor Cocula, who told us he was one of some 300 local people who follow the longstanding tradition of transforming hard basalt rock into practical appliances as well as works of art.

In fact, we could see such items in every corner of Cocula’s living room: sculpted busts, commemorative plaques and clever water filters along with the traditional mortars. “My ancestors have been making things like these for a very long time,” Cocula told me. “In fact, only recently a neighbor dug up a metate in the local cemetery which amazed all the craftsmen of the village. It appears to be some 600 years old, decorated with the head of a dog.

“The quality of workmanship is extraordinary. There are no tell-tale chisel marks on it anywhere — in fact, it’s so smooth it appears to have been machined. We can’t explain how it was done, but it’s proof positive that sculptors have been at work here for a long, long time.”

By now, of course, I was dying to observe the process by which these items had been made and I immediately accepted Victor Cocula’s offer to take me to the nearby basalt mines where the rock is extracted.

It turned out the mines — quarries really — were only a half-hour’s walk from the village. We climbed down into a long, deep manmade gully which seemed to go on forever. The steep walls on either side consist of basalt boulders undermined by decades of digging, and are anything but stable. “Over the years,” said Victor’s father, “we’ve lost five people to rock falls in these mines. Two of them died quite recently.”

We arrived at the family’s favorite spot along the trench and while his father deftly turned out a dozen “manos” (pestles), Victor walked me through the process of converting a rock into a sculpture.

“We are fortunate people here,” he told me as he tapped several rocks with a short hand pick. “If we need 100 pesos for something, we just walk up the hill to the mine and look for a rock that could be turned into a molcajete.”

He went over to a bowling-ball sized rock embedded in the wall of the trench, knocked the dirt off one spot and tapped the rock with the pointy end of his pick, producing small pits in the surface. “This rock is fine-grained but not too hard. See? All the holes are very tiny. Besides that, it has no sand embedded in it. The last thing people want is to find grains of sand in their salsa.”

Bruce

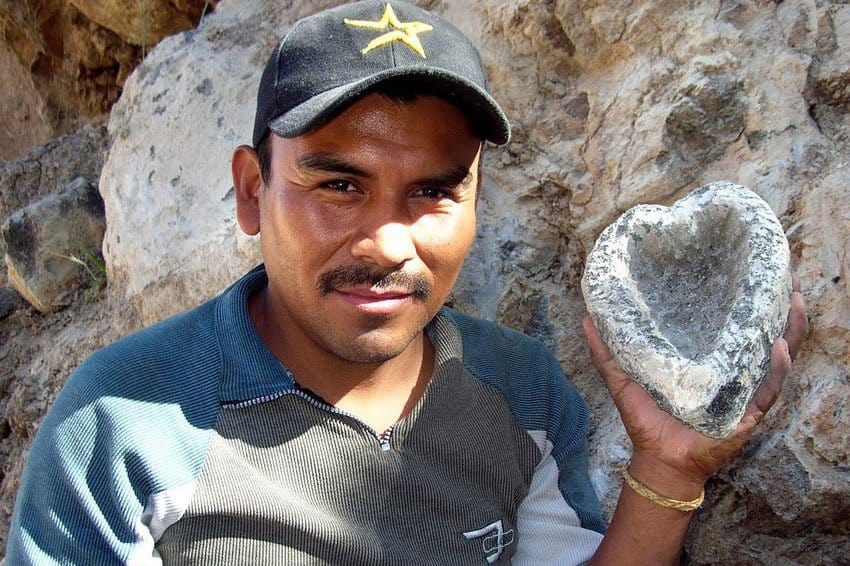

He lifted the rock and, like a true Mexican Michelangelo, said: “I see a molcajete inside. I could turn this into a five-inch-diameter round one or a heart-shaped one. Now, the round one would bring me 70 pesos while the heart shape will be worth 150 pesos, so I’ll go for the latter. OK, it looks like there’s enough rock here to put three legs on this mortar, but first I have to check if there are any natural faults.”

A few swift blows revealed just such a fault and the craftsman removed a one-inch layer, leaving the rock flat on the bottom. “Oops, not enough room for legs anymore, but it’ll still make a fine piece. Now I have to see if this rock has “hilo.”

This, he explained, means that the rock will fracture in the direction the sculptor intends, rather than “doing its own thing.”

“Qué bueno,” said Victor. “It has hilo,” and he deftly used the flat end of his pick to quickly give the rock the external shape he wanted. Then he turned the pick around and used the pointed end to begin hollowing it out. “These blows must be neither too heavy nor too light,” he commented as tiny chips flew everywhere.

“Don’t you ever get a piece in your eye?” I asked, noting that neither he nor his father was wearing goggles. “Ha! All the time,” he said laughing.

“Sí, sí,” chimed in his father, “chips in the eye siempre!”

[soliloquy id="66899"]

In spite of the danger and grit, the Coculas truly love their trade. “Some years ago,” Victor told me, “my family got together and decided we would try to create the world’s largest molcajete. We made one weighing 800 kilos and it was promptly bought up by a famous restaurant in Zacatecas.

“After that, we located a huge boulder of high-quality basalt and started work on an even bigger one. It took years, but last May we finally finished it. It’s 90 centimeters tall with a diameter of 1.90 meters and it weighs 3.3 tons. You can see it in the plaza of San Lucas, when you come to visit.”

Whether the Coculas’ mortar is the world’s biggest I will leave to the folks at Guinness to decide, but I can say that San Lucas is well worth a visit. The plaza may appear quiet and sleepy, but in almost every back yard, chips of basalt are flying.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.