Mummies are not uncommon in Mexico, especially in the arid north of the country. They have been found from pre-Hispanic and colonial-era burials and occur naturally, usually in above-ground burials such as crypts.

The most famous are in the city of Guanajuato, and have drawn tourists to the municipal cemetery for decades, especially after a campy movie in the 1972 pitted lucha libre wrestling legend El Santo against undead versions of them.

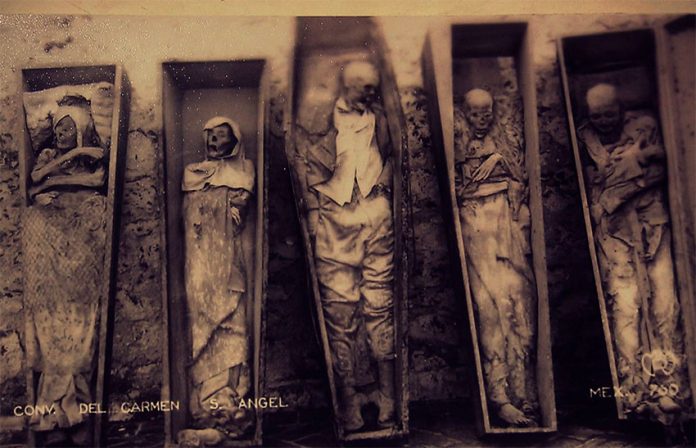

Mummification is very rare in wetter climes, but under the right circumstances it can still happen. The most famous example of this in Mexico City is at the El Carmen Museum in the fashionable neighborhood of San Ángel in the south of the city, distinguished by the tile cupolas overlooking Avenida Revolución.

This building is one of very few left in the Valley of México that date from the 17th century and is only a remnant of what it once was. Established in 1615 as the San Ángelo Mártir College, a theology school for men, it originally had various buildings and cultivated lands, but these disappeared after the Reform Law closed all the monasteries in 1858.

The church kept its original function, but the former monastery was used as a jail and a barracks before finally becoming the El Carmen Museum in 1938.

The museum is divided into 10 sections with the permanent collection dedicated to the life of the Discalced Carmelites that ran the monastery and school.

However, the most popular section by far is the mortuary chapel, located underneath the main altar in the church.

How the mummies got there is not exactly known. Stories about their origin vary, but one thread in common is that their existence came to light when Zapatista troops found them during the Mexican Revolution. One version of the story states that the Zapatistas brought them into the monastery building, but this is not likely.

More credible versions state that the Zapatistas found them while tearing up the floors looking for treasure, or they were moved here from a nearby church.

Another widely accepted theory is that they are the bodies of Juan de Ortega y Valdivia and his family, who helped to finance the construction of the crypt but the bodies have not been positively identified. They wear both men’s and women’s clothing, but it is possible that they were dressed after they were exhumed.

“They are a very important part of the cultural heritage because they provide much historical information about how people lived in the past, especially in Mexico in the 19th century,” Daniela Alcalá Almeida, spokesperson for the museum, told the EFE news agency. The bodies can provide information about the economic situation of the time and what the people died of.

The mummies are in very good condition because of the environment of both the crypt and the mortuary, which impede the flow of oxygen that helps in the deterioration of the corpses. The mummification process was helped by the dry conditions that prevent much of the normal decomposition.

Alcalá Almeida emphasizes that it is a kind of microclimate that promotes the conservation of the bodies. “If they were taken to another place, they would suffer changes that would not be positive.”

The mortuary crypt was used by the Discalced Carmelites for monks when they died, as well as important donors to the San Ángelo Mártir College. Monks’ bodies were removed after seven years, and their bones transferred to an ossuary. This was not the case with donors, who would stay in the crypt.

The mortuary chapel was located under the main altar of the church, a prestigious location for burial. Its prime location is underscored with frescos on the ceiling, which are in good condition, and with ceramic tile on the floor. The first paintings here were done on the upper parts of the walls and then on the ceiling vaults.

All are in the Baroque style of the 17th century, evidenced by the use of full shapes and round curves. Their good condition is surprising given the fact that while they have been cleaned on several occasions, they have never been restored professionally.

Mexico News Daily