Water is one of those things, like electricity, that many don’t consistently think about: its presence is really only made known by its absence.

Increasingly, water’s absence is putting its presence — or not — at front of mind.

Something a good friend of mine said to me last year during an extended springtime drought and water rationing in my city has stuck with me. Activists in Puebla had turned off the tap that delivered a significant portion of needed water directly to our city. They were angry because they needed water to fight the almost unheard of forest fires.

“With this water issue, we’re always just two weeks away from total societal collapse,” my friend said.

Oh, yikes. She was right.

Throughout the spring months in Xalapa last year, protests sprouted up around the city. Some colonias (neighborhoods) went for weeks without water. When this happened, they’d sometimes take drastic measures like blocking major roads until the authorities found a solution.

And honestly, who can blame them? Water might be our most basic need out there, important for hygiene too: Can you imagine not being able to wash your dishes for two full weeks? Or, like…your butt?

When supplies are scarce — and they often are — the city’s water authority puts out a rationing schedule. Different colonias take turns going without every few days, with notices going out like: “Colonia Zapata will have water pumped to them on these seven spread-out days next month. Here’s the schedule: plan accordingly.”

In my house, we don’t use lots of water, which means that even when there is rationing, we don’t usually notice. Lest you think this is a humblebrag, this isn’t because we are super conscientious but because we are dirty hippies, not showering nearly as often as we should.

Anyway. It’s only been a few times that we’ve done too many loads of laundry on an “off” day and used up everything stored in the tinaco, the giant plastic “Rotoplas” cylinder that most people have on their roofs.

How does water get pumped into these different places in the meantime? In order for homes to have water, you have to have enough pressure. In order to have enough pressure, there needs to be enough water to pump. Because most people’s tinacos are on their roofs, not enough pressure means no water getting to these homes. More of the distribution issue is about gravity than you’d think, actually.

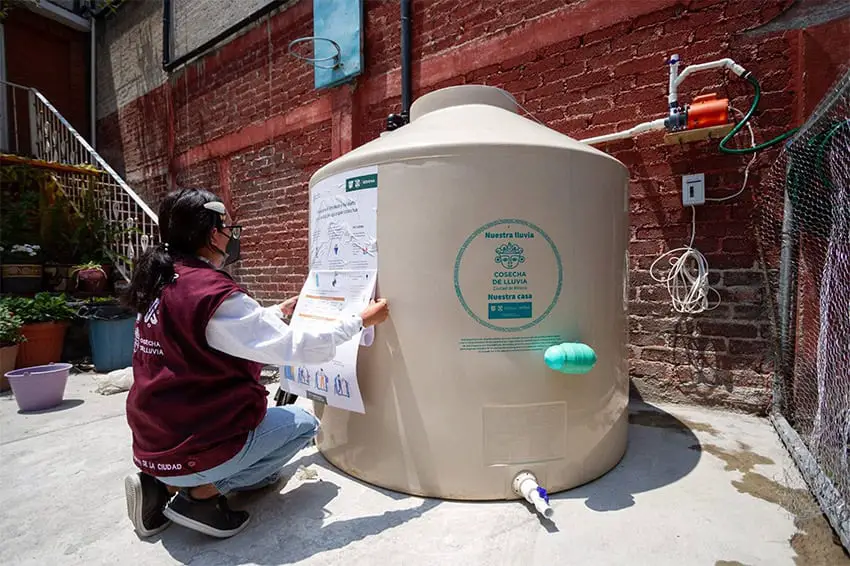

Some homes have a below-ground cistern and a “bomba” (a pump) which can help in these cases. It’s a nice feature for storing excess water until you need it, capturing the “spillover” once the tinaco is full for later. And some homes function without a tinaco, simply pumping water from a cisterna with their own electric pump when water pressure from the city isn’t enough to do the job.

So those are the mechanics. What I’m more interested in, though, is where this water actually comes from.

This is an important question as climate change and spreading urbanization increasingly means we face water shortages. Especially panic-inducing was the Trump Anger Machine rearing its head at Mexico over what normally would have been a routine water delivery. Water in the north and southwest United States is, you know, scarce.

As always, President Sheinbaum’s response was measured and reassuring — “Don’t worry, we’re handling it” — but in a way that we can actually trust.

We’ve got a deal with the U.S. regarding water along the border. Aging infrastructure, dwindling water supplies, and increased agriculture on both sides are majorly straining this agreement. There are plans for major infrastructure projects around the country. Great! Will it be enough in the meantime?

And where does Mexico’s water come from, anyway?

This simple question is actually complex, only slightly less so than asking where air comes from. Here’s the breakdown:

About 37% of the water that gets pumped into our homes and businesses comes from aquifers, or subterranean water. It’s pumped out for our use and is supposed to be replenished through rainwater. As the case of Mexico City shows, however, areas covered in concrete aren’t good about letting rainwater seep through the ground.

About 60% of the water Mexico uses comes from surface water, like rivers, lakes and streams.

And, of course, in order to distribute this water to the parts of Mexico without much water, a vast network is needed to get it to them. When there’s plenty of water to go around, it’s not an issue. But when drought has prevented water from replenishing our collective supply, protests like the ones I mentioned above ensue.

For now, things are calm-ish. In Mexico, about three-quarters of water goes to agriculture; fair enough. We all need to eat. About 15% goes to homes and industry, and about 5% to industries that take their water directly from the source, though I suspect that number is low.

In nearby Coatepec, for example, Coca-Cola and Nestle have direct control of nearly half of the aquifers, even as residents go without.

As a result, you can imagine that kind of anger directed at these companies when supplies get low.

What will this spring bring?

Here in Xalapa, at least so far, in Xalapa, I’m cautiously optimistic. But we’re just now entering the dog days, so there’s no telling quite yet. Tandeos (city-mananged rotation shifts of water availability by neighborhood) started around Christmastime this past year, though — they normally don’t start until the spring.

In the meantime, let’s all pray to Tlaloc. And maybe keep our eyes on and support all these new water infrastructure projects.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com.