The song was right: breaking up is hard to do.

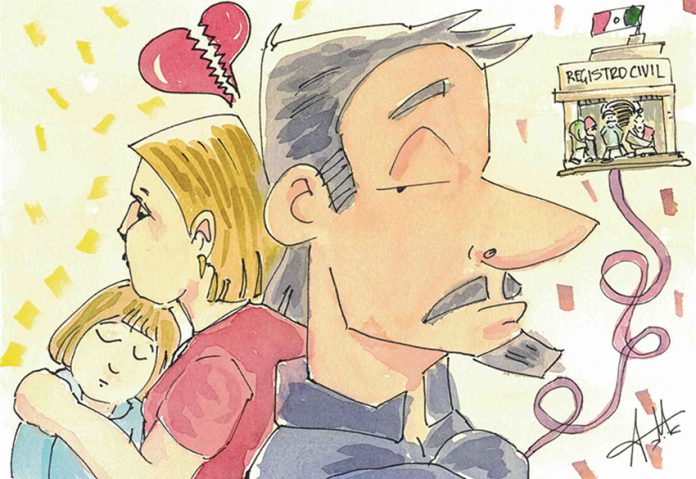

If you were married in Mexico and wish to not be anymore, then breaking up legally can be especially difficult. Figuring out your place within, as well as the actions you must take to navigate any legal system is hard enough. Figuring it out in your second language when conflicting advice and instructions abound can feel downright impossible.

The whole process has made me personally realize why, religious reasons aside, many married couples in Mexico simply decide to stay “separated” forever, never getting around to signing actual divorce papers.

I’m writing this on the day after my husband (technically, still) and I finally signed a legal agreement through a free state mediation service to dissolve our marriage and cement the specifics of the responsibility and care of our daughter. It gets us almost to the end of what has been a long, winding, and painful road to something I’ve been hoping to do for three years now. Now that the final pieces are falling into place, it feels like a weight is, at last, being lifted off of my shoulders.

Before getting too deeply into it, a caveat: this is not a “how to get a divorce in Mexico” article. I don’t have the legal expertise for it, and frankly, don’t get paid enough to do the extensive research that would be needed for such an article. I simply want to share my own experience as a long-term immigrant to Mexico married to a Mexican citizen. This is also not a “let’s publicly trash my ex” article, but a series of observations made from my own and others’ experiences.

The process differs by state anyway, the common thread among them being that you’ll need quite a lot of guidance in taking the correct of many possible steps (some of them landmines) to deal with what is likely one of the most emotionally consequential actions of your life. Most lawyers will talk to you initially for free, though, so if it’s a move you’re thinking of making, the office of someone recommended should be your first stop.

As foreigners, we don’t have the “home advantage;” legally, there is no home advantage, of course, but culturally and linguistically there certainly is, beginning with the fact that the Mexican party is likely to be surrounded by an extensive family network ready to lend them a hand. For us, reliance on a network of friends is pretty much it. And as I’ve said before, friends ain’t family around here. If you happen to be a woman with children, you’ve also got some deeply-ingrained and very specific cultural ideas about what it means to be a good mother to contend with. It’s tough on top of what would be tough even in your own country.

They say that you really get to know the person you married during a divorce. This, I’m afraid, is a sad fact wherever you are. After going through this experience, I’d add to it: when people are under a great amount of mental and emotional stress — and separation and divorce will usually get them to that point – then we tend to revert to well-worn cultural scripts.

The cultural scripts of Mexicans upset about the end of a relationship, I’ve found, can be quite dramatic (all these soap opera tropes didn’t come from nowhere). There’s drama, there are accusations, there are threats, there are assurances that a desire to no longer be with that person is evidence of mental instability. And once you’ve run the gamut one time, it’s possible that it will start all over again!

Another thing to be prepared for: there’s a certain innocence in many well-meaning non-Mexicans, possibly born of our generally Pollyanna view that people will mostly behave decently given the chance. Most Mexicans do not possess this naturally trusting disposition; on a cultural level, they know better than to simply take things at face value.

That trusting disposition that many of us have, then, can leave some of us feeling a bit like Charlie Brown tumbling backward when Lucy inevitably pulls the football away at the last moment until we knock the habit of trying to be fair and agreeable above all else. “Fair and agreeable” is not always how the game is played around here.

To be fair, the timing of our separation was difficult. “February 2020,” I believe, says it all. Most all institutions were closed shortly after, and many of the support systems I was planning on relying on throughout that difficult time were suddenly not available. My young daughter and I were now in a different house, without her dad and with very little real live contact with anyone. It was rough.

We’d previously agreed to use a mediation service through the CEJAV (a free state-wide center for alternative justice). Many states have similar institutions which allow you to resolve your differences both peacefully and legally, and divorce agreements are a large portion of what they provide help with.

The trouble came, however, with our first (online) session: after telling the mediator that we wanted to share custody of our young daughter, he told us that it would be impossible; one parent had to have primary custody. (Later — too late — I realized that shared custody had been written into Veracruz state law in 2019, something the mediator apparently had not been aware of.)

Our inability to find a solution we were both okay with eventually led to me filing a lawsuit: if you don’t go the mediation or jurisdicción voluntaria route with the help of a lawyer, then the only way to get a divorce, if you have a kid together anyway, is by literally suing the other person.

My husband convinced me to desist (which I recognized almost immediately as something I should not have done) as a condition of agreeing to the convenio that I’d wanted in the first place – the lawsuit was a means to that end. This is a legal agreement to both the divorce and shared custody, which I knew by then indeed was a possibility. Said convenio was drawn up but never paid for as promised, alas, and nearly two years went by before finally getting to the CEJAV, this time, in person, for two two-hour sessions to get it all done.

By the time we finally went, I’d been gearing up to once again find a lawyer to sue for exactly what I wanted in the convenio anyway, as I’d despaired of ever being told, “Okay, I’ve got time now; let’s go.”

But it finally happened, y’all. It took a while, and the pandemic didn’t help things. Me being a somewhat gullible and disoriented foreigner, at least when it comes to the law, didn’t help, either. But here we are. At last.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com