A country as old as Mexico always has a plethora of legends, some fantastical, some realistic but purely fictional. Then there are some that are probably based in truth, but who can say how much exaggeration and outright fabrication has happened along the way?

The legend of La Carambada — a 19th-century female highwayman who supposedly plagued the roads between Mexico City and Querétaro, robbing travelers of their money and valuables and giving them to the poor — falls somewhere between these last two.

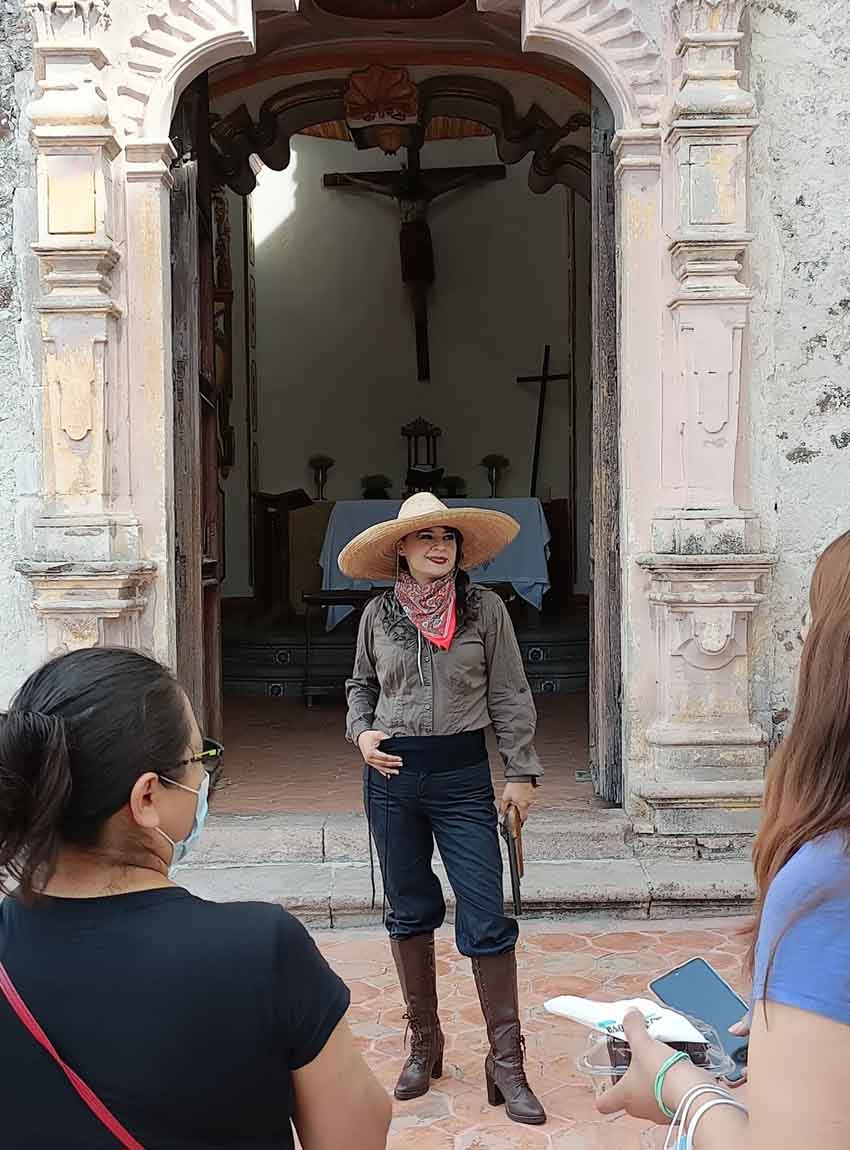

Was she in any way real or pure fiction? Either way, she’s one of Queretaro’s most popular local legends, appearing as a character in multiple local historic tours.

Mariana Álvarez Díaz Barriga, who leads the Querétaro historic tour group Leyendas y Mitos de Quéretaro (legends and myths of Querétaro), said that while her group understands that some elements of the La Carambada story are romanticized, they use her in their tours because “there do exist historic sources that say she existed.”

“I consider her to be the most important icon, or legend, in the representations of the histories of Quéretaro of this type,” she said. La Carambada’s story is still popular with queretanos, she said, something Álvarez attributes to her being “a Robin Hood type.”

Local Querétaro historian Delfino D. Leal Vega says, “She was a thief, but only because she gave to those in need by taking from those who owned the most in a perverse and corrupt regime in the Mexico of the late 19th century,” he said.

Among historic sources arguing for her existence is Queretaro’s own official municipal history, which talks about her as real, according to current-day Mexican chronicler Salvador Zúñiga Fuentes. He identifies her as a poor woman named Leonarda Medina. Other versions paint her as a wealthy young woman, once a companion to Mexico’s Empress Carlota, although most academics refute this detail. Further adding to the intrigue around her existence are 1880s U.S. news accounts of La Carambada’s capture.

Rod González, who also conducts historical tours of Querétaro, laughingly says that “every person in Querétaro has a different version of the legend.”

So did she ever exist? How much of the legend is true, if any?

Historian Valentin F. Frias — considered the father of Querétaro history and who lived during La Carambada’s time period — wrote in his book The Legends and Traditions of Querétaro that La Carambada did indeed exist. He identified her as Leonarda Martínez, not Medina, and said she was born in 1842 in the village of La Punta.

In 2018 and 2019, newspapers like the Garbancero Chronicler and Noticias de Querétaro published versions of La Carambada’s story, saying it was the version passed on through generations in Quéretaro. Their versions told how in the late 19th century, gangs of thieves on horseback were common. They frequently stole money and valuables from travelers on the roads around the city, robbed haciendas and stole shipments of gold and silver in transit.

La Carambada supposedly was part of such a gang, made up of people from the Querétaro villages of San Antonio de la Punta — where Leonarda was born — and Santa María Magdalena.

Leonarda knew how to ride bareback, dressed in men’s clothes, handled weapons with ease, and neighbors in La Punta spoke of her having been involved in a gang and stealing from a young age. As La Carambada, she warned victims to comply in a masculine and threatening tone, telling them they were surrounded by her partners in the woods, where she had strategically placed lit corn cobs around the area to look like there were glowing tips of cigarettes. She was also known for lifting her top at the end of her robberies, revealing her gender mockingly to her victims and bragging, “Look who just stole from you.”

According to Álvarez, the female bandit’s sobriquet came from the old expression “Ay caramba.” Whenever Queretaro’s residents heard of another of her bold exploits, they’d utter the phrase.

Many versions also contain romantic elements: a tragic love affair, a revenge plot and political intrigue in which she secretly assassinates Benito Juárez for turning a deaf ear on her pleas to not execute her lover, a soldier with the French occupying forces in Mexico slated for death once Juárez and his government took back Mexico. Leonarda is said to have vowed revenge.

Using her beauty, she supposedly got herself invited to a dinner party in 1872 at the home of Sebastian Lerdo de Tejada, then president of the Supreme Court. He ascended to the presidency in 1872 when Juárez died of a heart attack in office.

This version of the legend says Martínez caused that heart attack by placing drops of the slow-acting poison veinteunilla into Juárez’s champagne glass, killing him without a trace 21 days later.

The story of La Carambada also captured the imagination of journalists in the United States. One 1884 article in The Sunday Critic of Logansport, Indiana, reported as fact that “La Carambada, the woman brigand long a terror to travelers in this region, is dead at last, with a bullet in her heart. Her operations extended over many years and was of the most daring description.”

This article painted La Carambada as a femme fatale who would work her way into the good graces of male travelers and lure them outside of town with her in a carriage. She would then shoot them dead. The driver — perhaps paid for his silence — would then drive on to her appointed destination, where she would reunite with her gang. Her trickery was said to have baffled the authorities since drivers always told them that the victims had been robbed and killed by highwaymen but that the lady with them left unharmed.

When she finally came under suspicion, Leonarda decided to change her tactics and lure wealthy landowners to their abduction, having her gang negotiate the ransom while she was far away, targeting her next victim. But this strategy is said to have been her downfall, for she was captured after trying to abduct a wealthy landowner named Don Civelo Velázquez.

She was betrayed by one of her gang members and captured by the authorities. The rest of the gang tried to overtake her captors, but she was killed in the fierce gunfight that commenced. “One of her captors described her as a beautiful woman …. but with a wicked eye and a cruel-looking mouth when in repose,” one account reported.

According to Frias’ history, the end of La Carambada’s notorious career came slung over the back of a mule — presumed dead. She was taken to the hospital for an autopsy, where she was discovered to be alive. However, she’s said to have died shortly after making her confession to the Archbishop of Querétaro.

So while it’s probably nearly impossible to prove whether or not she really existed, La Carambada is proof of the maxim “never underestimate a good story.”

Leal believes it ultimately doesn’t matter whether the story is true.

“It is very important to reserve, value, and recover the collective memory — the myths and legends [of the Mexican people],” he said.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán last year and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.