This month marks the anniversary of William Walker’s ill-fated 19th-century attempt to establish his own country in the northwest of Mexico.

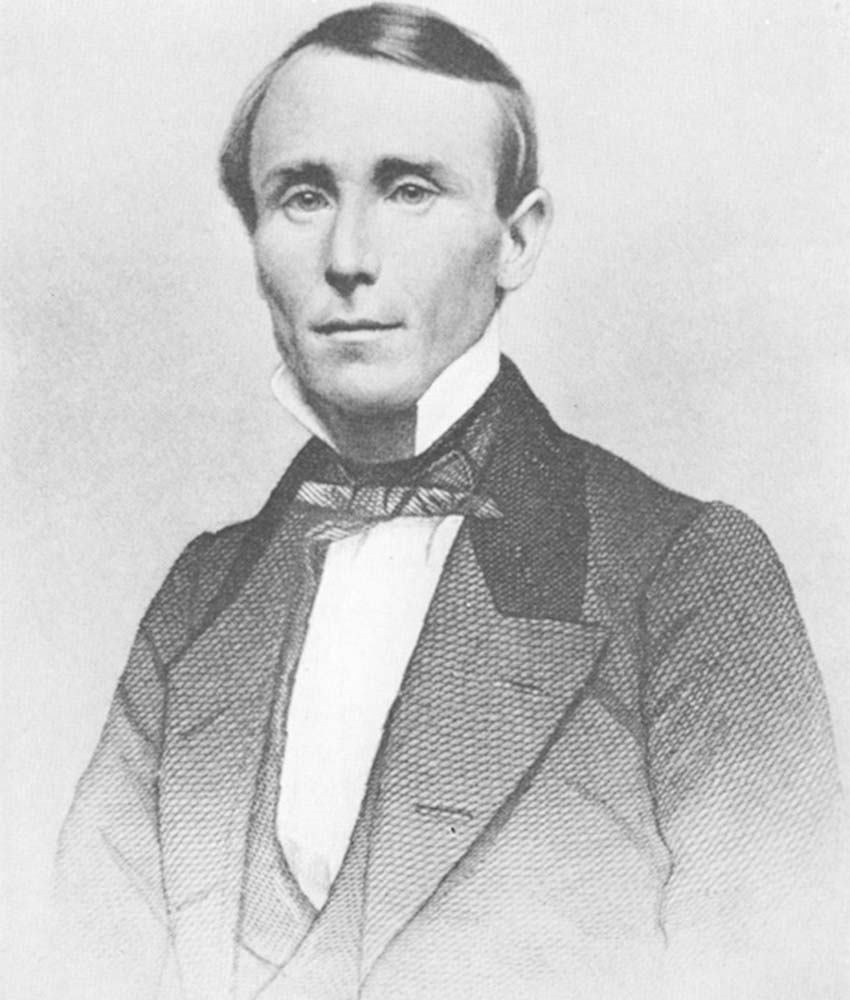

Walker, a United States physician, lawyer and journalist, was also what was then called a “filibuster” — someone looking to conquer lands in the Americas in the years between the Mexican-American War and the Civil War in the United States. At one point, he briefly controlled parts of Sonora and Baja California.

Since many of his ilk were from the U.S. south, it is common to attribute their motives to establishing new slave states. Far more important was the doctrine of Manifest Destiny.

By the time I went to school in the 1970s, this doctrine was explained as being about the United States’ destiny to extend its territory to the Pacific Ocean. But in the mid-19th century, that “destiny” included all of the Americas. There was also an economic incentive to the filibusters’ actions: latecomers to the California Gold Rush who found themselves broke were ripe for adventurism.

Mexico received warnings of filibuster activity from the U.S. government as early as 1851 since it was in violation of the U.S. Neutrality Act. Various filibusters made their way to Mexico, but William Walker was the most “successful.”

Highly intelligent, educated and internationally traveled, he made his way to San Francisco from New Orleans in his early 20s. With the Gold Rush over and dreaming of empire, Walker’s target was Sonora and its mineral deposits.

His first attempt to get a foothold in the area started with a trip to the Sonoran port of Guaymas in early 1852, asking the Mexican government to form a mining settlement. That request was denied.

Walker returned to San Francisco to start his quest in earnest, raising money by selling certificates that would later be redeemable for land in Sonora. He bought arms, other supplies and a ship called The Arrow. However, the U.S. army intervened and confiscated the ship and most of its supplies.

Unwilling to give up, he and 45 men booked passage on another ship, leaving San Francisco in October of 1853. They made it to Guaymas, but Mexican officials there became wary and turned them away.

When the ship stopped for supplies in La Paz, Baja California, Walker and his men decided to take over what was the capital of the peninsula. They caught the territory during a change of power and proclaimed the Republic of Lower California, with Walker as president.

Word of Walker’s takeover of Baja made it to the U.S., where it was very popular. It brought men, but precious little in the way of provisions. Communications with his base in San Francisco were spotty at best, and the organization there disintegrated.

But by January of 1854, Walker found himself with about 300 men and supplies taken from local ranches (with IOUs, of course).

He had never forgotten the original plan to invade Sonora, and Baja California had little to offer Walker. So on January 10, 1854, he declared that Baja California was part of the new Republic of Sonora.

He had not stepped foot on the mainland, but he decided to remedy that.

It is not known why Walker decided to march to Sonora instead of commandeering boats to cross the Gulf of California. But march they did, taking a ranch near Todos Santos and renaming it Fort McKibben.

Walker still hoped for shiploads of supplies, but they never came. The filibusters continued northward, sacking anything of value in that impoverished area, which further turned the local populace against them.

Authorities in Mazatlán and Mexico City were aware of the situation but were slow to respond. A contingent of 250 Mexican soldiers did not arrive in La Paz until December 12, 1853, sent by authorities in Sinaloa.

Walker made it to Ensenada, then turned east to Sonora. However, he was unable to cross the Colorado River delta. Meanwhile, Mexican soldiers were in pursuit.

Problems of hunger, thirst and battles prompted desertions until by early May of 1854, Walker had fewer than 35 men. He tried to retreat to San Vicente, but the Mexican garrison had captured it, so the ragtag bunch of adventurers had to hightail it to the border. It was far better to turn themselves over to U.S. military authorities than to surrender to the Mexican army.

On May 8, they finally crossed the border, where U.S. soldiers were waiting for them along with a bunch of curious onlookers.

Walker’s invasion and “republics” lasted only eight months, but they took a toll on Mexico-U.S. relations and the political and economic situation on the Baja borderlands. Although the United States government never sanctioned Walker’s activities and even warned Mexico about them, the incursions started when the U.S. was negotiating the Gadsden Purchase. The Mexican government was worried about the Americans’ intentions toward the Baja Peninsula in general.

The Baja California border area was sparsely populated to begin with, but over a third of that population left for safety reasons during and after the invasion. It forced the Mexican government to militarize the area.

After surrendering to the U.S. military, Walker was taken to San Francisco to stand trial for violating the Neutrality Act. However, because of the popularity of what he did, the jury acquitted him in just eight minutes.

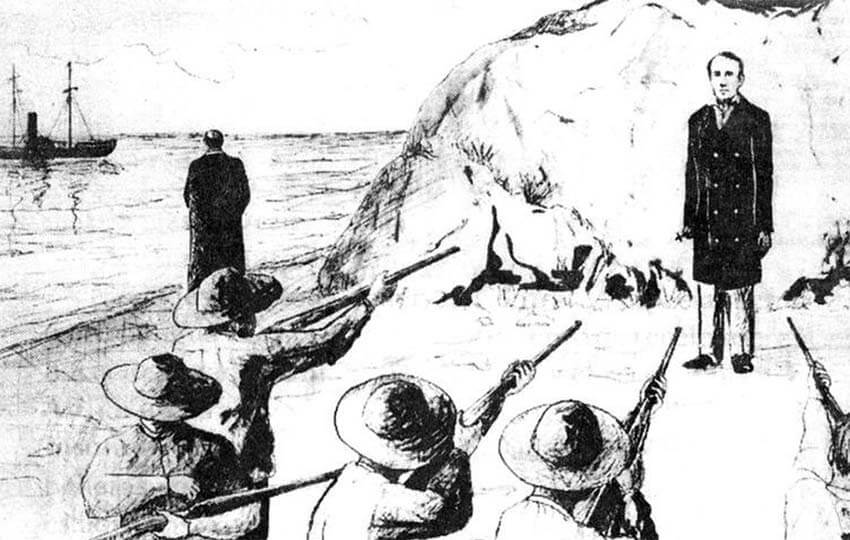

A free man again, he would then try his luck in Nicaragua, becoming “president” of that country for 10 months before being kicked out. His last filibuster was in Honduras in 1860, but the British did not take kindly to such activity in their backyard and so captured him and turned him over to Honduran authorities. He was executed that year at the age of 36.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.