José Clemente Orozco Farías is the grandson of one of Mexico’s greatest muralists and bears his name.

“He’s also one of my best customers,” the owner of an English bookstore told me, “and you should see what he’s doing over at his place, which is called Impronta. I think you’ll find it interesting.”

The other day I did just that. The word impronta means impression in English, which didn’t give me too clear an idea of what sort of establishment it was, but I figured it was going to be plenty noisy inside, judging from its location right in the heart of the city of Guadalajara.

Wrong on that score! A little passage led us into a marvelously quiet patio with tables and chairs and a menu offering coffee and imaginative desserts like Ganache de Pistache (Pistachio Fudge). “Well, well,” I told my wife, “Impronta is a café.”

José Clemente Orozco Farias was there waiting for us, the most peaceful of men with the bushiest of beards. “Let me show you around,” he said, leading us into a room filled with bookshelves.

On a table were some of the most unusual books I’ve ever seen: the paper was beautiful, each letter was beautiful, the bindings were beautiful. Some of the books were large-format collections of fine art, while others were thin but elegant printings of a single poem.

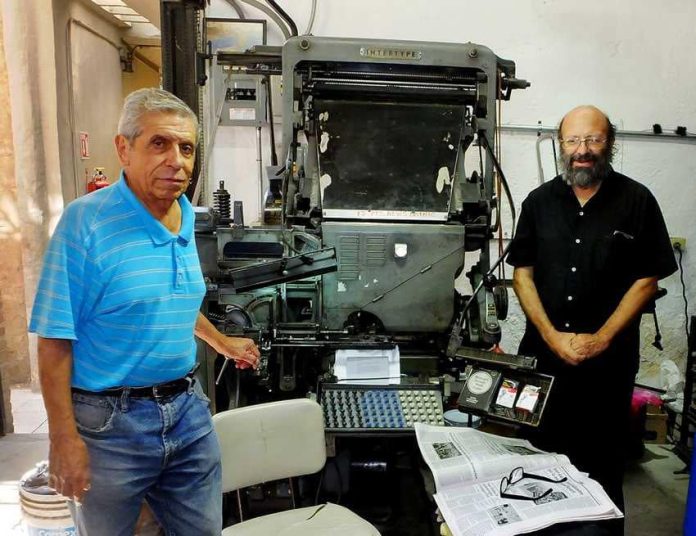

“We made all these and we sell them here,” explained Orozco, who told us to call him Clemente. Just when I had concluded that Impronta is a bookstore, Clemente took us into another room, a big one, filled with very large machines. It was like walking into a museum of the history of printing, only most of these machines were in use, operated by the few old-timers left in town who not only knew what typesetting meant, but were experts in the craft.

“This is Rafael Villegas,” said Clemente. “He’s going to print your names the good old way.” Don Rafael sat down in front of a strange-looking keyboard with 90 pre-QWERTY keys, punched out some letters, pulled a few levers and PSHHH! With a release of steam out popped a little lead ingot saying “John and Susy Pint,” mirror-image of course.

“Careful, it’s hot,” said Don Rafa as he placed it in my hand. Clemente then put the ingot face up on another machine, inked it by hand, ran a drum over it, and out came our names in the center of a fine sheet of expensive paper.

“This,” I thought, “is something every new millennial needs to experience,” and, in fact, Clemente told us, Impronta regularly offers workshops on the forgotten kind of printing that actually lets you feel the letters on the other side of the paper.

Our tour took us through several more rooms containing creaking cabinets and chests of drawers filled with wooden and zinc engravings of every style of letter imaginable, some of enormous size.

At last we returned to the café where I asked José Clemente Orozco Farías just how he got interested in the art of book making.

“I grew up in Mexico City and came to Guadalajara when I was 17 to finish high school,” he told me in excellent English. “I was thinking of going into architecture, but then I went off to the U.S.A. for college, to Dartmouth, where I got very interested in art history. One thing I liked was that I could take all kinds of courses and explore other disciplines.

“Well, I was in a work-study program and they sent me to a studio that produced posters for one of the cultural centers. They commissioned me to design posters for silk screening and I first learned about typography here. I had always done drawing — it’s in the family, from both sides, in fact — but here I focused on print making.”

Dartmouth’s library, I should mention, houses one of the most famous murals by Clemente’s grandfather, José Clemente Orozco, entitled The Epic of American Civilization, a U.S. National Historic Landmark.

Clemente ended up studying at the Rhode Island School of Design. “At that time they weren’t using computers; everything was done photomechanically, so that’s where I first came into contact with lead type and I learned typesetting.” Later he accepted a fellowship at the University of Texas Press in Austin “where I learned the more specialized craft of book design. In fact, I designed 20 books for them.”

In 2008 Orozco Farías and friends rescued their first cast-off Linotype machine and, the following year, started up the predecessor of Impronta in a garage, printing little booklets “in order to keep the machine running.”

Famed Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco was one of the 20th century’s major artists, but few remember that he was also a skilled and versatile print maker. So is his grandson, Clemente, who is doing marvelous things in downtown Guadalajara.

The newspaper El Informador calls Impronta “a unique space in the city,” where one can find gorgeously printed and bound works available nowhere else.

An example is Impronta’s first book, Caminar – Walking by Henry David Thoreau, 92 pages. This is a bilingual edition — English and Spanish — of Thoreau’s most popular lecture, which discusses the importance of nature to mankind and how, in Thoreau’s words, “people cannot survive without nature, physically, mentally, and spiritually, yet we seem to be spending more and more time entrenched by society.”

This beautifully bound book is a collector’s item, printed on 100-gram Corolla Damasco paper. You can see what it looks like by visiting Impronta’s elegant web page. You can also see a short video clip of the Impronta linotype machine in action here.

Sarah Smith of Dartmouth’s Book Arts Program says Orozco Farías and Impronta Casa Editora are part of a worldwide revival in handmade books.

The next time you’re in Guadalajara, you can discover for yourself what Clemente is doing by visiting Impronta and Café Diamante at Penitenciaría 414, between Libertad and La Paz. Their telephone number is 38252641 and they are open weekdays 9:00am to 5:00pm.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.

[soliloquy id="54934"]