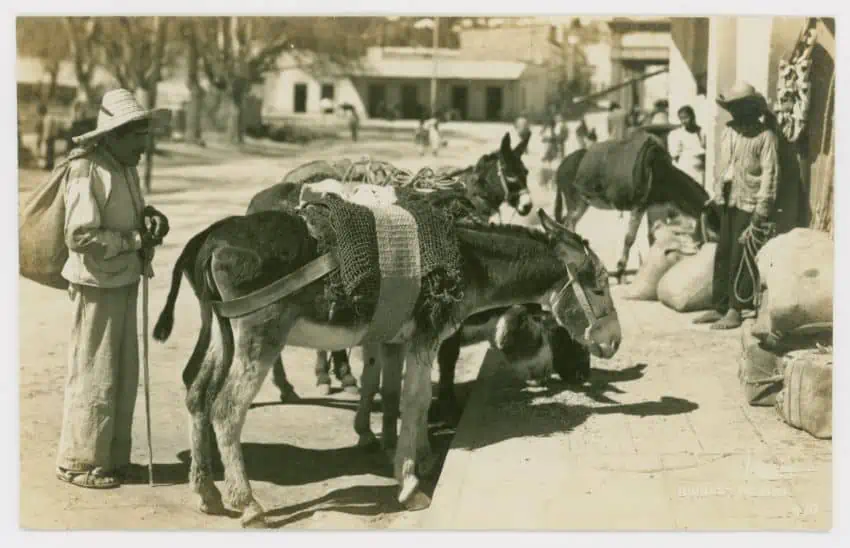

Few images are more stereotypical of Mexico than a gray donkey carrying large bundles led by a guy in a large sombrero. But that reality has all but disappeared.

Is the donkey itself far behind?

The donkey is not native to Mexico, but its importance was established very early in the colonial period. There were no domesticated pack animals in Mesoamerica; a certain class of people did that job.

The Spanish quickly imported donkeys, which can carry up to four times their body weight and far more than any human.

The animals became indispensable in farming, trade and mining. Over time, a gray Mexican variety developed, not due to breeding but rather simple survival. As purely work animals, only the hardiest survived and bred.

Donkeys are still an important symbol of Mexico’s agricultural past, representing strength, hard work and, yes, a lack of intelligence. (Poor students are classically called burros.)

The truth is, the donkey is intelligent. The stupid reputation comes from being disobedient, which happens when the donkey is mistreated, according to Raúl Flores of the Burrolandia donkey sanctuary in Otumba, México.

For over a decade, the Mexican media and even National Geographic in Spanish have reported that donkeys are in danger of extinction here. They base their assertion on data from Mexico’s census agency, Inegi, which states that there were 1.5 million of the animals in Mexico in 1991 but only 585,000 in 2007 and 300,000 in 2020.

However, the Veterinary School of the National Autonomous University (UNAM) disputes these findings. According to officials there, numbers have gone down significantly, but the animal is nowhere near extinction.

They estimate the donkey population to be somewhere around 3.2 million, based on a UN Food and Agriculture Organization report that ranks Mexico fourth in the world for donkey numbers.

Marian Hernández Gil, who coordinates the school’s donkey research and conservation efforts, said that the animals are still an indispensable part of sustainable agriculture in highly isolated areas of Mexico, areas in which it is impossible to travel or farm with vehicles or machines.

The school is still concerned about the donkey’s well-being in Mexico. UNAM partnered with the United Kingdom-based Donkey Sanctuary project to work in 13 states that account for about 75% of the country’s donkey population. One of their activities is to promote donkey care at state veterinary schools.

The reason for the discrepancy in numbers between Inegi and the UN is that donkeys are hard to count. They are often in highly isolated areas. Inegi’s numbers come from counting those animals that are corralled on farms and other rural work units. They do not include, according to UNAM, wild or otherwise roaming populations of donkeys.

There is no doubt that donkeys are “extinct” in the day-to-day life of the vast majority of Mexicans.

Many Mexicans now live in urban and semiurban areas where the animals usually have no economic value. Even in many rural areas, the mechanization of farming has taken the donkey’s place in most agriculture, just as trucks took away its transport function.

By the 2000s, the value of a donkey had fallen to as low as 500 pesos per animal. The fear among conservationists was that their value was so low that the rest of the population would simply be culled because they were too expensive to care for.

However, the value of burros has risen more recently into the thousands of pesos (yes, you can buy live donkeys through Mercado Libre!). Does this mean donkeys are making a comeback?

Not quite. The rise in price is most likely due to a huge demand for donkey hides in Asia. These hides are boiled to extract a collagen called ejiao, used in traditional medicines and cosmetics. This market demands millions of hides per year and has put documented strains on donkey populations worldwide.

There are no large-scale efforts to conserve the Mexican donkey, but one town prides itself on its dedication to the beast of burden: Otumba is a rural municipality in the heart of Mexico’s pulque country, an hour outside Mexico City and 10 minutes from Teotihuacán.

The town calls itself the “cradle of the donkey” and has celebrated a “Donkey Day” since 1965. Back then, donkeys carrying jars of pulque and aguamiel (maguey sap before fermentation) were a common sight but already starting to disappear.

Donkey Day is May 1, celebrated with a Donkey Fair starting at the end of April. The fair includes a donkey costume contest, donkey polo matches, and a donkey “Formula 1” race. Unfortunately, the fair has been canceled in both 2020 and 2021 because of the pandemic.

There is still a way to support the town’s dedication to the donkey. It is home to a nonprofit private donkey sanctuary called Burrolandía, run by the Flores family since 2006.

It claims to be the first organization of its kind in the Americas, home right now to 57 donkeys. Most are rescues, with about 10% born at the sanctuary.

The sanctuary fervently believes that the donkey is in danger of extinction in Mexico and that the vast majority of those in the country are poorly cared for, even abused.

In normal times, the sanctuary supports itself through tours of the facility and the surrounding town (using miniature trains and other vehicles outfitted with donkey ears), a restaurant, sales of feed for the donkey and even an adopt-a-donkey program.

They need about 1,000 visitors a month to remain solvent but have had only a trickle since the pandemic started. Feed costs alone for the animals run almost 2,000 pesos a day.

In November 2020, the sanctuary put out a call for donations as it had cut rations to the donkeys as much as they could. As of this month, the situation is still quite precarious, with the Flores family stating that the sanctuary is flat broke.

Tours are still available, but it is necessary to book an appointment before you go. The sanctuary can be contacted through its Facebook page.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.