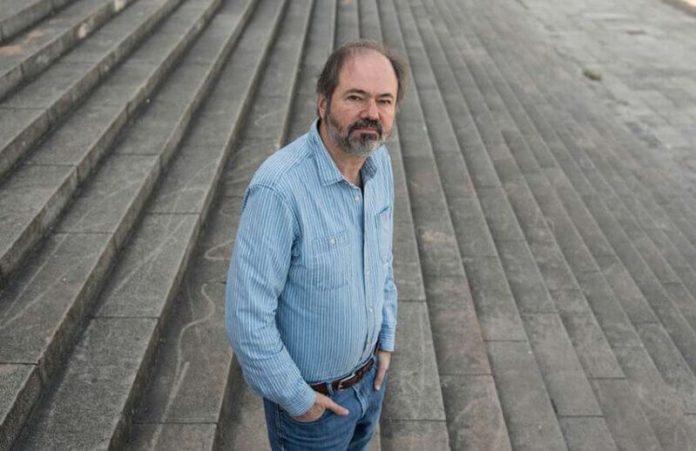

Celebrated Mexican novelist Juan Villoro compares his home of Mexico City to an onion or a lasagna — in either case, it’s multilayered with a history going back to indigenous times.

His latest work, a nonfiction book, focuses on the many, ever-unfolding layers of the city’s past, present and future.

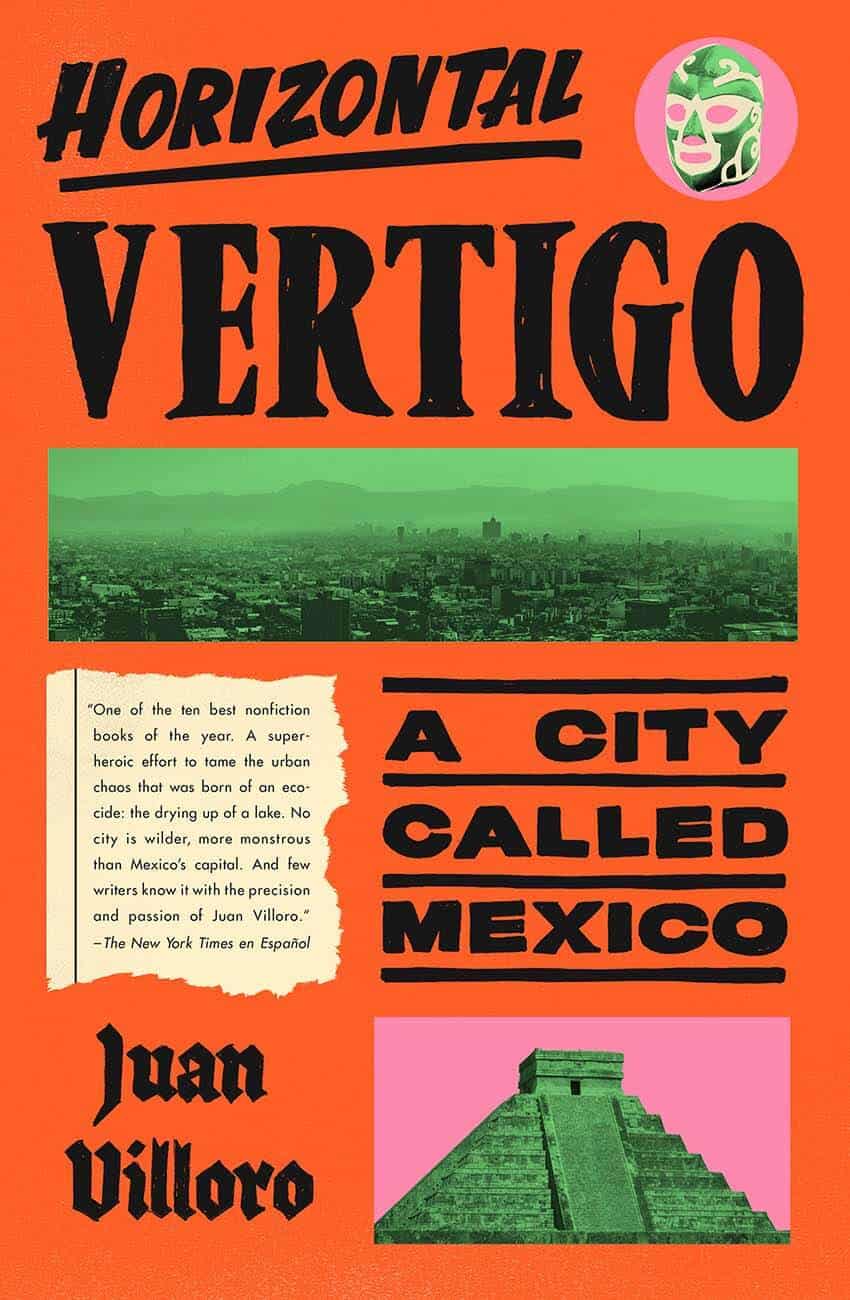

Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico is Villoro’s paean to a place he knows intimately, ranging from childhood explorations of tramways to conversations as an adult with prominent poets in coffeehouses. Published in English in March, it was named a top 10 best nonfiction book of the year by The New York Times en Español.

The book’s title is a reflection of the earthquake threat that has led Mexico City’s architects to traditionally build outward, not upward. In it, Villoro shares his love of bike tacos and his frustrations with cheering for the Mexican national soccer team.

He also discusses the multiple tragedies Mexico City has suffered, including the earthquakes of 1985 and 2017 and the current COVID-19 crisis. Each time, Villoro has seen the city and its residents, or chilangos, show resilience.

Comparing the coronavirus pandemic with Mexico City’s earthquakes, Villoro said, “The COVID emergency has been quite different. After the quakes, it was urgent to do something, and the people came together.”

That included himself, as shown in a heart-wrenching chapter on the 1985 earthquake. But “in the present circumstances,” he said, “the most useful thing is to avoid other people, a challenge for a gregarious society.”

The book reflects that gregariousness by depicting the individuals, fiestas and destinations that have enlivened Villoro’s pre-COVID experiences of the Mexican capital, going back to his childhood.

As Villoro explained, “My father was born in Barcelona and my mother in Mérida (two separatist places: no wonder they got divorced!). I had no sense of belonging. Suddenly, playing in the streets, riding illegally on a tramway — discovering the labyrinth — became my most important existential experience. I decided to be part of that place.”

Mexico City is a place with many historical connections: from the Aztecs to colonial Spain to Mexican independence to the 20th and 21st centuries.

“To some extent,” Villoro reflected, “the Aztec city is a hidden, underground citadel. It is impossible to dig a hole in midtown Mexico without practicing a kind of archaeology. Then you have the colonial city, built by the Spaniards in imitation of the Renaissance utopias; the modern; the postmodern; even the futuristic city that has been the ‘natural’ location for such films as Elysium and Total Recall.

“You cannot achieve a global description of so many historical influences, but you can give a taste of them.”

The book conveys its author’s ongoing relationship with the capital in a complex way. Each chapter represents a separate story, yet all are interrelated in depicting the vibrancy of Mexico City. The chapters are divided into categories such as “City Characters,” “Ceremonies” and “Places.”

“The structure of the book resembles the way we move through huge cities like London, Sao Paulo or New York,” Villoro explained.

Yet, he noted, “it is impossible to write a comprehensive narrative map of such a gigantic place as Mexico City. I decided to follow different paths, similar to the lines you take on the subway.”

He called his experience of the capital “both personal and foreign.”

“Some places belong to my sentimental education, and others have to be investigated,” he said. “Some reading ‘lines’ of my book belong to an intimate approach of the city. Others depend on a journalistic survey.”

One of Villoro’s continuing fascinations is the city’s many unique fiestas, from the traditional Independence Day celebrations to the more recent Zombie Parade. He even explores the legendary 1965 gathering to await a parade of UFOs that somehow never arrived.

On Independence Day, “People don’t take the streets to celebrate the national identity or with claims to recover Texas. Independence Day is a great opportunity for being together,” he noted.

“The same happens with the Zombie Parade,” he added. “Believing in the underworld and in the living dead are less important than assuming a dress code to be part of the crowd. There is a strong sense of carnival in our public gatherings; you can feel the energy of the multitude that creates a provisional community.”

“The end of the gathering and the empty streets raise an unsolved mystery,” he said. “Where does that energy go?”

It was not the streets but the underground that inspired the first reflection included in the book — a meditation on the Metro and its connection to Mexico’s indigenous people. Villoro wrote it in May 1994 while teaching at Yale University, a few months after the Zapatista uprising broke out in Chiapas.

“The Zapatistas put the life of the Maya and other original people of Mexico on the current political agenda,” he said. “For centuries, the Indians were regarded as part of the past, the ‘disappeared’ builders of pyramids. The Zapatistas said, ‘Let us belong to modern Mexico.’

“At that time, I was asked to write something about Mexico City and decided to recreate the subway system, taking into account the Zapatista claim.”

In the book, he notes that there is a pre-Hispanic pyramid at one Metro station — Pino Suárez — while other stations have Aztec names, from Tacuba to Coyoacán to Iztapalapa. “All pre-Hispanic mythologies start and end in underground places,” he said.

“Suddenly, the ancient past became incredibly modern to me!” he reflected. “I never thought I was starting a book, but this new approach to the Mexican traditions was instrumental to begin a series of texts that, eventually, would lead to Horizontal Vertigo 25 years later.”

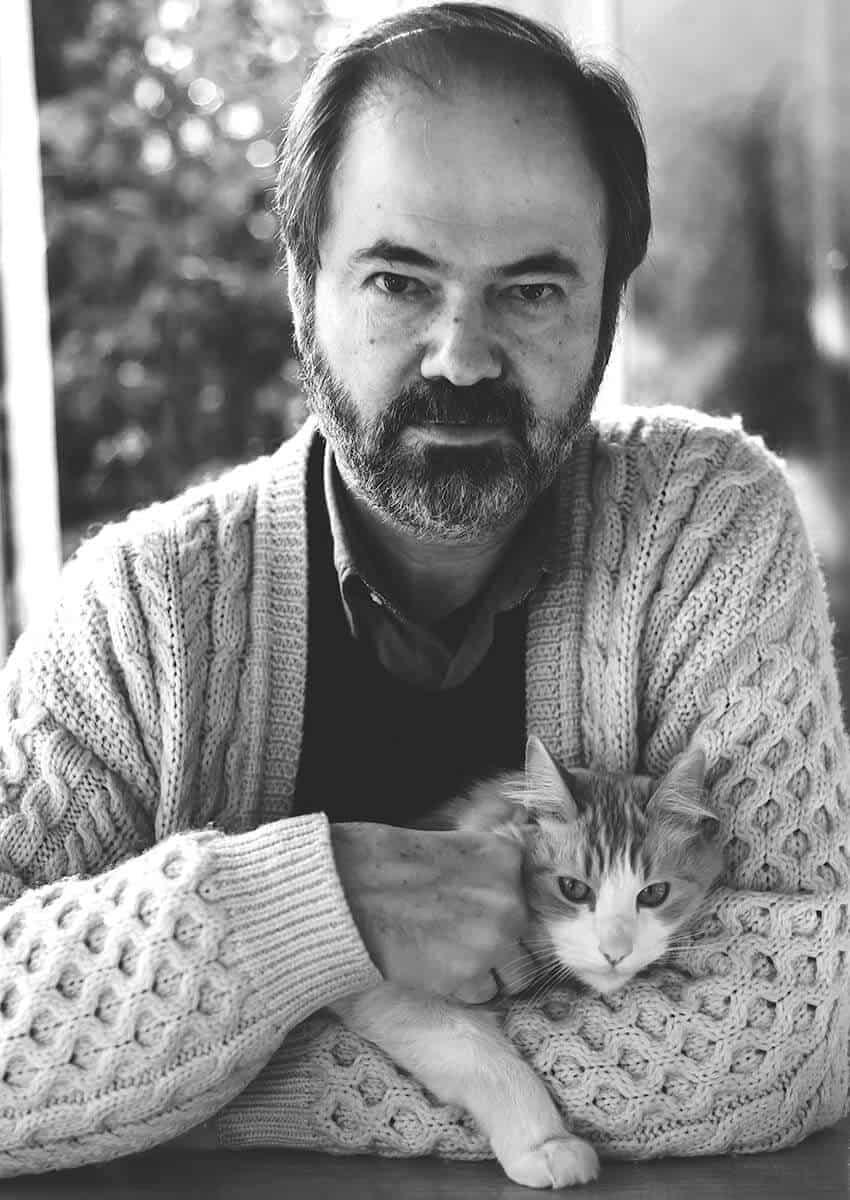

During the past quarter-century, Villoro and the city that was his constant subject each experienced significant developments. In 2004, his novel El testigo, or The Witness — a novel about a Mexican intellectual who returns to his homeland after living abroad for two decades — won him the Herralde Prize, a Spanish-language award given annually by the Barcelona-based publisher Anagrama.

Five years later, in 2009, he witnessed Mexico City challenged by a pandemic that eerily presaged the current one — the swine flu outbreak that occurred during an interchange in the capital by the then heads of state Barack Obama and Felipe Calderón. In the book, Villoro records scenes that sound familiar today, such as calls for mask-wearing and social isolation.

Although the book was published before Mexico City’s latest tragedy, the Metro disaster on May 3 that killed 26 people, when asked about it, Villoro called the tragedy “the chronicle of a death foretold.”

“It was dubbed the Golden Line and covered the longest path in the subway system,” he noted. “But it was designed to accomplish political ambitions, not to serve the people. Neighbors knew that [the accident] could happen anytime.

“It is the third disaster in a short period of time. Are our politicians capable of caring about something else than winning an election?”

As for the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, he reflected, “We have survived in strange isolation. The main lesson is that we have acknowledged how much we need ourselves.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.