When Bowdoin College professor Carolyn Wolfenzon Niego conducted interviews with some of Mexico’s top contemporary authors, she noticed a common theme in their work. All were interested in the concept of the ghost and how it was shaped by Mexico’s past and present.

Guadalupe Nettel, for example, evoked otherworldly themes in multiple novels, including Después del invierno (After the Winter), when a Mexican character living abroad in Paris goes to the famed Père Lachaise cemetery on the Day of the Dead to commune with her deceased neighbor, who is buried there.

In El complot de los Románticos (The Romantics’ Conspiracy), Carmen Boullosa imagines a group of deceased writers, including Dante Alighieri, traveling on rats from New York City to Mexico City for a literary conference; when they reach the Mexico-U.S. border, they find a surreal sight — movie screens bearing stereotypical images of each country, such as idyllic Norman Rockwell scenes for the United States and Los Supermachos for Mexico.

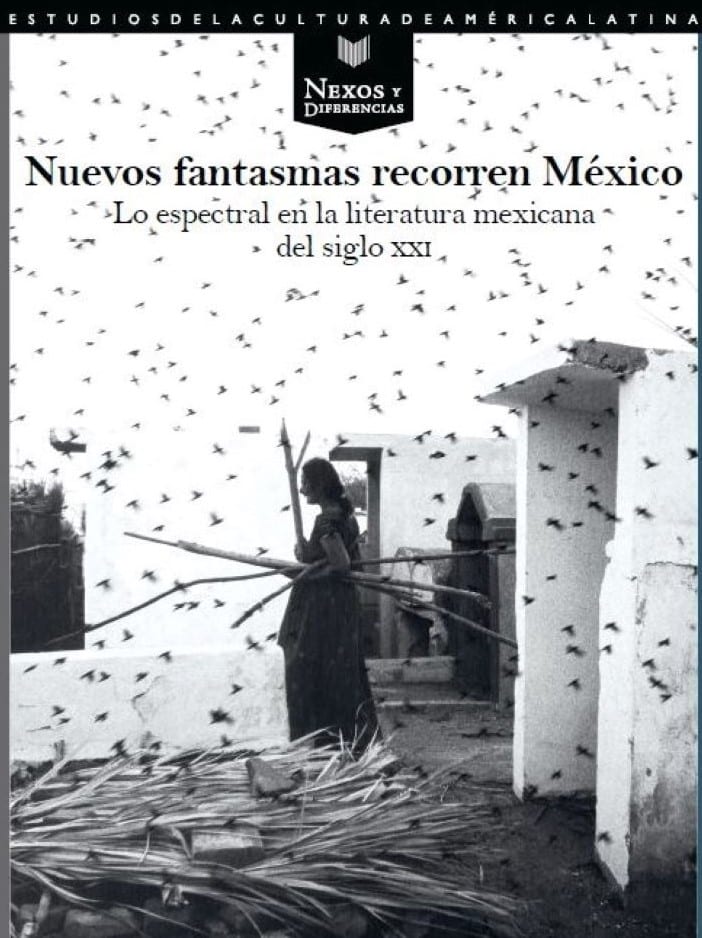

Fascinated, Wolfenzon launched a deeper exploration into the theme of the ghost in the authors and their works. The result is her new book, Nuevos fantasmas recorren Mexico: Lo espectral en la literatura mexicana del siglo XXI (New Ghosts Run Rampant in Mexico: The Specter in Mexican Literature of the 21st century).

“I realized that many contemporary authors are fascinated with ghosts,” Wolfenzon said. “Ghosts are very present in different ways in contemporary Mexican literature.”

The book is based upon interviews conducted between 2013 and 2016 with eight Mexican authors. In addition to Nettel, Boullosa and Herbert, she spoke with Valeria Luiselli, Yuri Herrera, Emiliano Monge, Daniel Sada (who has since died) and Elmer Mendoza.

All are novelists except for the journalist and nonfiction writer Herbert, whose books include a study of a real-life tragedy — a little-remembered massacre of the Chinese population of Torreón during the Mexican Revolution.

Wolfenzon, who is from Peru, interviewed each of the authors for the Lima-based journal Buensalvaje.

“Before the interviews, I read a lot of their books,” Wolfenzon said. “It happened that I started to notice the topic of ghosts was very present.”

So were references to two mid-20th-century novels by famed Mexican writers, both of which feature ghosts — Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo and Aura by Carlos Fuentes. As Wolfenzon explains, Pedro Páramo is set in Comala, “a town made up of ghosts” that reflects the idea of convivencia, “living together with the past.” In Fuentes’ Aura, the present intersects with the age of the French intervention, in a house in Mexico City shared by the protagonist, Felipe Montero, along with the ghosts of a general named Llorente and the Empress Carlota herself.

Wolfenzon said that while there are echoes of these novels in the contemporary authors she examines, they all “depart from Pedro Páramo and Aura, do something different. What they are doing … is connecting the idea of the ghost and different topics. There’s a diversity in the way they use the figure of the ghost.”

A professor in the Department of Romance Languages at Bowdoin, Wolfenzon’s previous book was titled Death of Utopia: History, Antihistory and Insularity In The Latin American Novel. In her new book, she takes a similarly comprehensive approach, suggesting that in contemporary Mexican literature, the concept of the ghost can be found in both traditional and nontraditional depictions.

Although contemporary novels include the familiar portrayal of a ghost as the spirit of a dead person, Wolfenzon also sees parallels in them between ghosts and characters who are alive but ignored by society. These include the early-20th-century Mexican poet Gilberto Owen, who goes unnoticed by New Yorkers while living in the metropolis in Luiselli’s novel Los íngravidos (The Weightless).

Wolfenzon also analyzes the inhabitants of the nightmarish city of Remadrin in Sada’s novel Porque parece mentira la verdad nunca se sabe (Because It Seems Like A Lie, The Truth Is Never Known) seems like a lie. There, the corpses of protesters are transported in a truck to a mass grave, while each of the city’s still-living inhabitants must repetitively perform a single, separate menial task.

Such a soul-crushing existence reminds Wolfenzon of the souls condemned to hell in Dante’s Inferno — as well as a new Comala. “In general, all Remadrin is a city of ghosts,” Wolfenzon said.

She also asks whether a place can be a ghost — such as the U.S.-Mexico border in its otherworldly portrayal in Boullosa’s El complot de los Romanticos. “[Boullosa] is allowing that the border between the U.S. and Baja California is a ghost in a way, a line [that is] kind of nonexistent, no matter the divisions,” she said.

In what Wolfenzon calls “a very imaginative novel, and, in a way, hilarious,” Boullosa depicts a border demarcated by movie screens projecting stereotypical images such as Rockwell’s all-American depiction of youths on a fishing expedition and the violent imagery in Jose Orozco’s mural Katharsis.

“We always have a border in our minds that is kind of ghostly,” Wolfenzon said, “all the images … stereotypical things about both countries.” She notes that such images in the media influence “the way you create your own picture of the countries even before getting there.”

While these images have a ghostly presence in Boullosa’s novel, there is a ghostly absence in Herbert’s nonfiction book La casa del dolor ajeno (The House of Others’ Pain) about the 1911 massacre of the immigrant Chinese population of Torreón. He attributes their deaths to the army of president Francisco Madero.

Before the Revolution, there was a vibrant Chinese community in the city, Wolfenzon said. Yet, half the community — 300 people — died in the massacre. “[They were] killed just because they were Chinese,” she said. “Julian calls it xenophobia, hate of the Chinese people.”

When Herbert visited the Museo de la Revolución de Torreón, “it emphasized the victory and very good things about the Mexican Revolution,” Wolfenzon said. “It did not say anything about what happened in the massacre of 300 Chinese people in the community of Torreón” — save for what she calls a “small, tiny” mention.

Wolfenzon received a scholarship from Bowdoin to visit Torreón, including the museum.

“For me, it was very interesting that the museum is built [in the former home of] one of the Chinese [individuals] expelled,” she said, referring to the doctor J. Wong Lim. “His house was stolen. They created a museum on top of his house … on top of the grave of [some] of the Chinese people they killed. There is no trace left of the rich, interesting, good community that used to live in Torreón before the massacre.”

Wolfenzon recalled that when she interviewed Herbert, he talked about going to the city center in search of physical evidence of the former Chinese community and finding neither their houses nor their businesses, with the only evidence located in archives.

“The places he mentions are ghosts,” Wolfenzon said. “They just were not there. He said it was difficult to reconnect everything.” In addition to the deaths of 300 people, “things were expropriated; things were created on top of those spaces. He spent many hours in the archive to see how this community used to be.”

Wolfenzon said that the concept of the ghost is present in literary depictions of “some of the traumas in Mexico,” such as the Tlatelolco massacre of 1968 and the fact of current migrants “trying to escape narcotrafficking, violence, maybe Covid in the present moment, and looking for a job.”

In Monge’s novel Las tierras arrasadas (The Devastated Lands), which is about a pair of migrants who are kidnappers, “He makes a parallel to cantos, songs of the Conquest … a circle of repetition. The idea of trauma is present in the idea of the ghost.”

Reflecting on Mexico and its colonial legacy, Wolfenzon said, the nation’s colonial past is not completely solved.

“It is latent in contemporary Mexico. It has a meaning of bisagra, past and present connected, a colonial ghost, in a way,” she said. “Yuri Herrera’s character Makina, in a way, represents La Malinche a little bit. She has things in common with her, how [La Malinche] has, in fact, not been completely abandoned in the actual Mexico of the 21st century. Many values, ideas and problems are unresolved from that period in dealing with new problems of the present.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.