Last year, members of the Guadalajara-based group Jalisco Desconocido located and explored the remains of the abandoned Hacienda de Ibarra, hidden deep inside a canyon at the north end of the city. More recently, the team was able to visit isolated and hard-to-reach La Florida, one of Mexico’s most elegant casonas (mansions) and one of the favorite haunts of president Porfirio Díaz.

La Florida, first known as Villa Aloha, is in the little town of Atequiza, Jalisco, just 10 kilometers north of Lake Chapala. It is said to have been constructed around 1876 by the powerful Cuesta-Gallardo family.

“For them,” said columnist “El Duque de Tlaquepaque” in the newspaper El Informador many years ago, “this was just a country house, but today we might catalog it as a sort of combination palace and pavilion. It served as a luxury rest stop where Porfirio Díaz and Carmelita and their elegant entourage could tarry for a few days before continuing their journey from the capital to the paradisiacal Lake of Chapala, which, at the end of the 1800s was très a la mode as the place to vacation during Semana Santa (Holy Week), thus inaugurating in Mexico (and of course it had to happen in Jalisco!) that phenomenon which today is known as TOURISM.”

The entrance to the two-story Casa La Florida was graced by a stunning statue popularly known as The Muse, cast by French sculptor Antoine Durenne, and all the walls were covered with beautiful murals. It is also said that the place was furnished with imported materials like Czechoslovakian stained glass, a French floor and Austrian crystal.

In 1896, La Florida was one of the few sites chosen by Lumière cinematographers Bon Bernard and Gabriel Veyre to film several of the first movies ever made in Mexico.

Jalisco Desconocido’s visit to La Florida is presented in a well-made video clip on YouTube. I recently caught up with the filmmaker, Luis Abarca, and asked him to tell me more about his latest adventure.

“I heard about this resplendent casa as a child,” Abarca said, “but only recently did I make an effort to visit it. The first thing I learned was that the place is situated on private land, so it looked like it would be impossible to go there, but I found out there’s an irrigation canal right next to the old building. Well, in Mexico all rivers, lakes and even canals are public property, so it was just a case of following the canal …”

Having arrived at Atequiza, Abarca’s group studied the layout of the area and soon discovered that the canal they sought was only some 500 meters from the Teatro (theater), another elegant building commissioned by the Cuesta-Gallardo family and now used as the local casa de cultura (municipal culture building). Jalisco Desconocido’s story, told by Abarca, follows:

“We started walking, and soon we found the canal, which was full of water. We could see there was a trail alongside it, but the trail was on the other side, so we divided ourselves into three groups to go look for some way to cross over. Finally we found a place where a tree had fallen across it. We could hardly see that log because it was hidden by lots of weeds! Well, the first guy to cross this “bridge” was really agile, and he just zipped over it like it was nothing. Then it was my turn. Bueno, I only took two steps, and I slipped because the bark covering that old log was rotting and coated with slimy fungus. The only way I could get across was by sitting and sliding along, like riding a horse,” Abarca said.

“So I got to the other side, but the next one to try was a lady who started walking and got halfway across. She panicked and almost fell off the log. ¡Híjole! There she was with her arms around the tree, hanging from it like a monkey, her feet dangling above the water! So I went back to rescue her,” he said. “Now, the water was ice cold, but it wasn’t deep, maybe one meter at the most. Still, there were all sorts of brush in and above the water, and if you fell, you would get tangled up in it. So I helped her get back on the log, and then we made it to the other side.”

The trail was between the canal and a chain-link fence that, the group had been told, had a hole in it at some point.

“So we walked along, and sure enough we found a rusty, broken place where you could get through,” he said. “Next we came to a curious area. It was all flat and looked as if it had once been a lawn, but today the grass is really high. I’m 1.8 meters tall, and it was way over my head! So we couldn’t see a thing, and we started to come to trails going in different directions. All I could do was keep trying to head where my GPS said the old mansion had to be.”

The grass was growing so incredibly high because the Santiago River was nearby and its water had partially flooded the area. What this meant was that they were soon walking through a sort of swamp, up to their knees in mud.

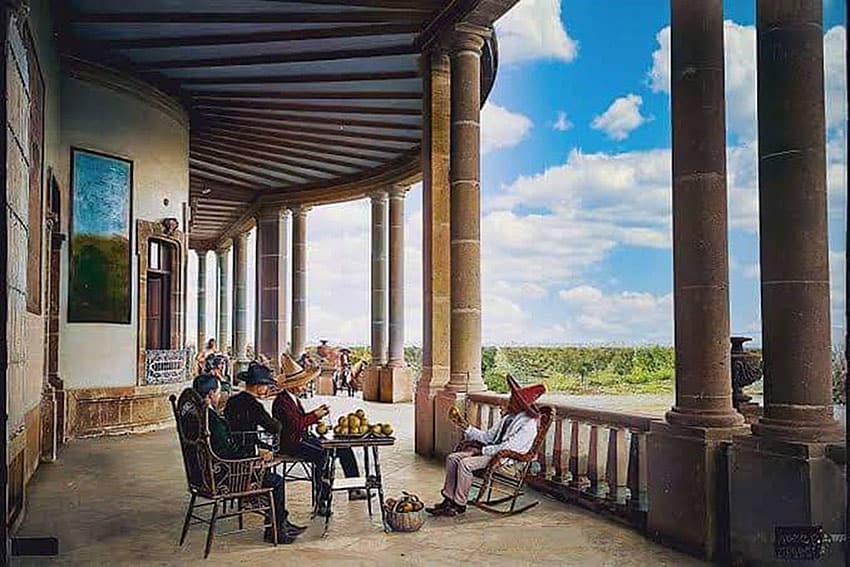

“After about 10 minutes of this, we came to another fence, which we followed for a while until we came to another hole,” he said. “Once we got through that, there we were, in front of Casa La Florida, right at the main entrance. Here, you go up some stone stairs and you are on the porch that you see in all the old photos, the place where the statue of The Muse once stood, the place where you see Porfirio Díaz and personalities of the day posing. Back in those days, there was an orchard of orange trees in front of the house, and it was those orange blossoms that gave the villa its name: La Florida, the flowery place.”

According to Abarca, most abandoned haciendas have been stripped of everything that could possibly be carried away, but not La Florida.

“Here you can see doors and gates and learn about little things like the kinds of locks and keys they used. Everywhere on the walls, you can see the remains of what look like paintings originally made on cloth that had been fixed to the walls,” he said. “The second floor has no rooms, only a big terraza illuminated by oval windows. This house is among the best-preserved I’ve ever seen, and by far it is the most beautiful!”

Another visitor to La Florida who was smitten by her beauty was that flamboyant Informador columnist, who apparently got to see the place while it still retained some of its old splendor:

“Yes, el Presidente received the royal treatment in those sumptuous salons of La Florida, whose elegance, even after 100 years, remains unscathed and fills us with nostalgia for bygone days. The first time I entered the grand salon, I felt I had walked into Palazzo Gangi, where the immortal Luchino Visconti directed his most celebrated film, Il Gattopardo (The Leopard), where we were carried away by an ethereal waltz, along with the charisma of Burt Lancaster, the good looks of Alain Delon and the sensuality of Claudia Cardinale. Yes, it was that captivating and unforgettable scene that overpowered me as I stood within the aging walls of La Florida …”

Today, La Florida lies neglected and literally disintegrating, even though concerned citizens in the municipality of Ixtlahuácan de Membrillo have been battling for over five years to save this extraordinary house from the elements and the encroaching tendrils of nature.

But, says the newspaper Milenio, the old building is now the property of a company dedicated to making chemical solvents and explosives, whose owners apparently have not yet heard the sound of that ethereal waltz echoing from the walls of the venerable Casa La Florida.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco for 31 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.

[soliloquy id="136743"]