I fell in love with Mexican folk art while working toward my undergraduate and graduate degrees in Latin American studies at the University of Kansas. Later, during frequent business trips to Mexico, I visited many of the country’s fine museums and learned more about this art, its diversity and the culture it reflects.

One type in particular, the exvoto (sometimes called retablo), captured my imagination.

An exvoto is a votive painting, examples of which first appeared in the 16th century and became very popular in the 19th. Painted on a piece of metal somewhat larger than a standard United States car license plate, each exvoto gives thanks for, or in some cases requests, divine help in solving a problem or saving the petitioner from some sort of harm.

A few just show an appreciation for some unsolicited development or occurrence.

Whatever its nature, each exvoto depicts the saint involved and an illustration and written description of the favor granted or the miracle or action performed. Usually painted for a fee by an untrained individual with limited education and artistic training, the petitioner hangs it in a church or in the home.

These traditional exvotos focus on health concerns or surviving life-threatening situations. The ones I find most appealing are set within the context of some historical event, such as a soldier giving thanks for not having been killed or wounded in a particular battle.

I also am partial to those that, in addition to giving thanks for whatever reason, reveal some aspect of daily life of everyday people, such as street, village and farm scenes.

I always wanted to own some of these — not for their antiquity, but rather for the history and culture of Mexico they evoke. Unfortunately, I only ever found ones I liked in museums. Several years ago, however, I discovered that a number of artists continue to paint exvotos, albeit with a more modern perspective.

Health issues remain a favorite subject, for example, but they often reflect previously unknown medical conditions being treated in a modern hospital instead of the home.

More interesting, perhaps, are the other subjects many of these exvotos address — ones seldom, if ever, seen in those painted prior to, say, 1950.

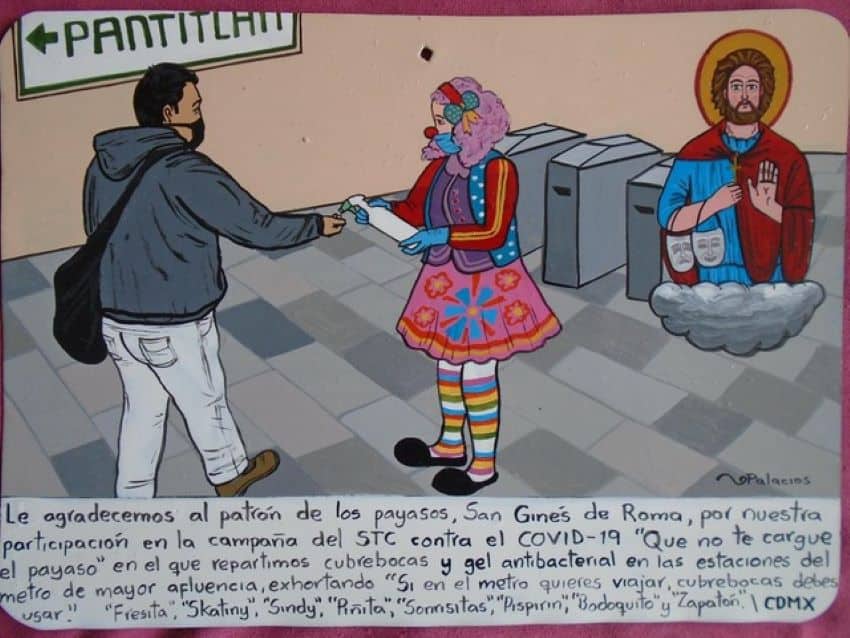

Many highlight important historical events, legends, folk dances, customs, and indigenous traditions. Others treat subjects from popular culture, such as disliked national and foreign politicians, television and movie personalities or lucha libre wrestlers and other sports athletes. Then there are those that address serious social issues, such as unemployment, emigration, prostitution, gay rights and the status of women.

The actual events portrayed in these modern exvotos, along with the names of petitioners, generally are fictitious. It is not inconceivable, however, that most of them could have taken place.

Some contemporary folk artists have been criticized for painting scenarios contrary to traditional Christian teaching, a prime example being a prostitute petitioning a saint for a favor.

However, the religion of many Mexicans is a mixture of pre-Conquest indigenous beliefs and the faith introduced by the Spanish. A national survey conducted by the National Autonomous University found that 95% of respondents pray, at least occasionally, for the intercession of the Virgin of Guadalupe, who is a common figure evoked in these works.

Since it is doubtful that all of these people lead exemplary lives as defined by an established church, such exvotos represent authentic expressions of faith well within the context of Mexican spirituality.

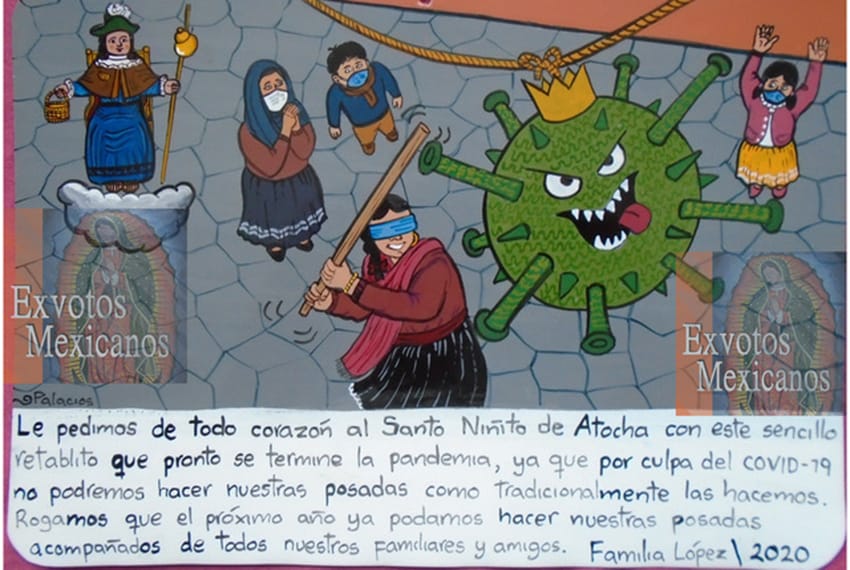

Another criticism leveled at times against contemporary exvotos is that some treat life-and-death situations with too much humor. It is my experience, however, that “too much humor” and “Mexican” do not go well together. As a people, they are addicted to humor, which is one aspect of the culture that I find so appealing.

No subject is off-limits except, perhaps, national symbols. A favorite topic treated with humor is death which, given the current pandemic, is not far from anyone’s mind.

Unlike the popular view held in the U.S., death is viewed in Mexico simply as a continuation of life on another plane, best illustrated by the Day of the Dead celebrations. Nowhere is the treatment of death with humor more evident than in the calaveras literarias, funny epitaphs of varying lengths and poetic resonance written for lovers, friends and relatives who are still among the living.

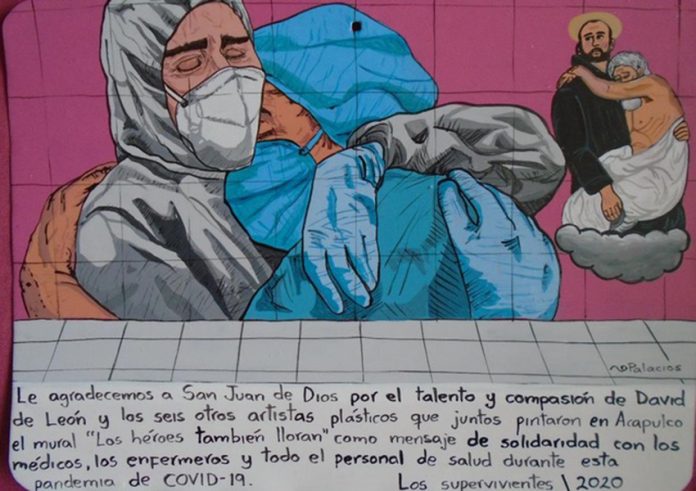

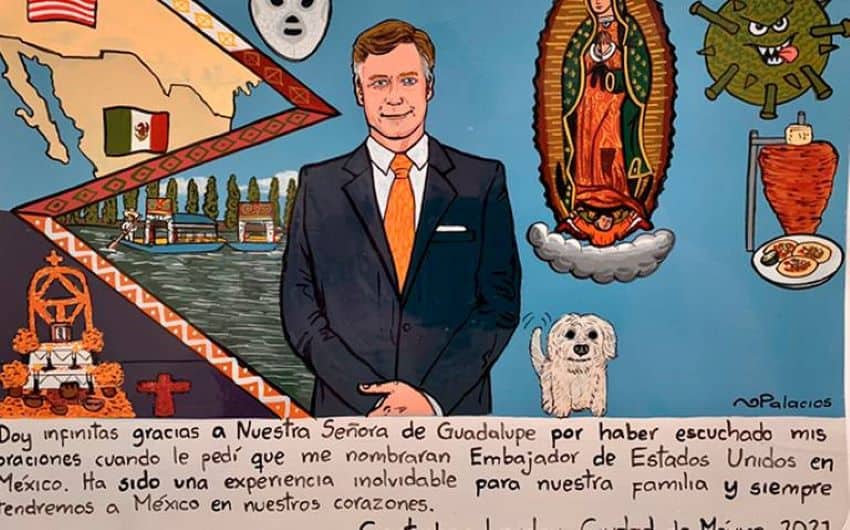

I collect the exvotos collaboratively painted by contemporary folk artist Flor Palomares and her husband Gonzalo Palacios of Puebla. They recently made the rounds on social media for having painted four exvotos commissioned by Donald Trump’s outgoing ambassador to Mexico, Christopher Landau, perhaps thinking of a tradition going back to Renaissance Venice, when officials in high positions commissioned the paintings to give thanks to the divine for having achieved their post. Landau, who commissioned his before leaving his Mexican posting in January, thanked the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Over the years, Flor and her husband and I have become good friends, and during my yearly visit to Puebla we enjoy sitting together in one of the city’s outdoor cafes discussing possible subjects for new paintings.

The pandemic has kept me at home, but we have continued to brainstorm ideas via emails and phone calls. After I saw their first work depicting the coronavirus, we started to collaborate on paintings focused on the Covid-19 pandemic.

Over the last year, our collaboration has resulted in a number of works focused on different aspects of people’s reactions to it.

Some represent our combined efforts. For those exvotos, I came up with the ideas, wrote the narratives and roughly (very roughly) sketched the pictorial parts. Flor and Gonzalo were left with the far more difficult task of executing them, as shown here with the English translations of the narratives.

For additional information on these artists and their works, you can see their work on Gonzalo’s Facebook, Instagram or Twitter. Their exvotos can be purchased on their Etsy store, or you can contact them directly via email at exvotosmexicanos@gmail.com to commission one yourself.

Mexico News Daily