The cigarette butt just might be the biggest little polluter on the planet.

According to the World Health Organization, up to 10 billion of the 15 billion cigarettes sold daily are disposed of in the environment, and a 2011 research paper says the butts contain a wide variety of chemicals, over 50 of which are known to be carcinogenic to human beings.

Unfortunately, the filters on these cigarette butts are really tough and won’t disintegrate for as much as 15 years. During all that time, their toxic ingredients are leached into the soil or water with serious consequences.

In 2021 a Mexican company called Eco Filter inaugurated a plant in Guadalajara dedicated to detoxifying and recycling huge quantities of cigarette butts collected by volunteers all over the nation. How they do it and how they got started make for a fascinating story.

In 2012, National Autonomous University biologist Leopoldo Benítez was working on his thesis and looking for something that could break down cigarette butts.

He went on a field trip to Michoacán, where he spotted oyster mushrooms growing on a log. He decided to bring a few samples back to his university lab in Iztacala, México state.

“This fungus breaks down wood, which is cellulose,” he reasoned. “So it should do the same job on cigarette filters.” More than 90% of the world’s cigarettes use cellulose acetate filters.

Next, he presented the idea to his teacher and started carrying out tests. What he found was that the fungus, Pleurotus ostreatus, not only broke down the cellulose but also neutralized the toxic substances in the cigarette filters.

How does it do this? Engineer Eduardo Solís of Eco Filter explained it to me.

“The toxic substances in the cigarette butt are hydrocarbons, and the fungus produces enzymes that attack the bonds between carbon and hydrogen. So if we have a long chain, it gets broken down into simpler substances that the fungus can introduce into its metabolism without any problems. And that’s how it degrades all those chemical substances present in cigarette butts.”

Excited by what he had found, Benítez teamed up with Paola Garro of the Technological University of Mexico (UNITEC), who suggested that they start a project to give “a second life” to cigarette butts, turning them into useful materials.

The pair announced their findings on social media and set up a network of representatives (whom they call Eco Filter Ambassadors) all over Mexico to get local people to collect cigarette butts. In 2019, they started a pilot plant to turn them into useful cellulose in México state.

The process worked well, and word of their success spread.

It spread not only among environmentalists but also came to the attention of Philip Morris México, who liked the work being done by these young Mexicans to resolve a problem that the tobacco industry had been unable to deal with.

With Philip Morris’ assistance, they made plans to build a much larger plant — the first of its kind in Latin America. It was inaugurated in Guadalajara in July 2021.

Thanks to the help of one of Eco Filter’s 500 ambassadors, I was able to pay a visit to the newly opened plant, which is located on a quiet street just south of Guadalajara International Airport.

I was impressed by the fact that the personnel there looked and spoke more like university professors than operators of an industrial plant. I was even more impressed when every one of them accompanied us throughout our tour of the building, answering our questions and contributing to the conversation with anecdotes and insights. It was unlike any factory tour I’ve ever been on.

We started out in front of an enormous bin filled to the top with plastic bottles full of butts.

“Here,” Solís said, “we receive millions of cigarette butts (colillas in Spanish) every month, and in this new plant, we now have the capacity to process up to 10 tons of them every year.”

“We have a tendency,” he added, “to ignore the presence of cigarette butts on the ground, but if you start to look for them, you will find them everywhere. To get people to collect them, our ambassadors organize “colillatones” all over Mexico.”

Colillatón is a made-up word that could be translated as “butt-a-thon” in English. The event gets large numbers of people off their bottoms and outdoors, walking about and continuously bending over to pick up cigarette butts — wearing gloves, of course.

“These colillatones,” Hilda Margarita Castro of Eco Filter said, “really open people’s eyes. They begin to notice just how many cigarette butts are lying on the ground all around us. There are billions of them! One participant said, ‘I walked along the curb of just one city block and I found 280 colillas! I couldn’t believe it! I follow that very same sidewalk every day … but I never noticed them!’

“Other people say things like, ‘I’m a smoker, and I decided to start putting my cigarette butts in a bottle. Well, I couldn’t believe how quickly that bottle was full!’ After filling two or three bottles, people start to think, ‘Wow, I’m spending a lot of money on cigarettes that I could be spending on something else!’”

Next, we went to the room where the cigarette butts are removed from the plastic bottles and dumped into trash containers. The people who do this work, said our guides, are obliged to wear hazmat suits equipped with special filters for breathing.

If you think one cigarette butt is stinky, imagine what a whole trash can full of them smells like!

The bottles, our guides commented, sometimes contain surprises, such as chicken bones and fingernails.

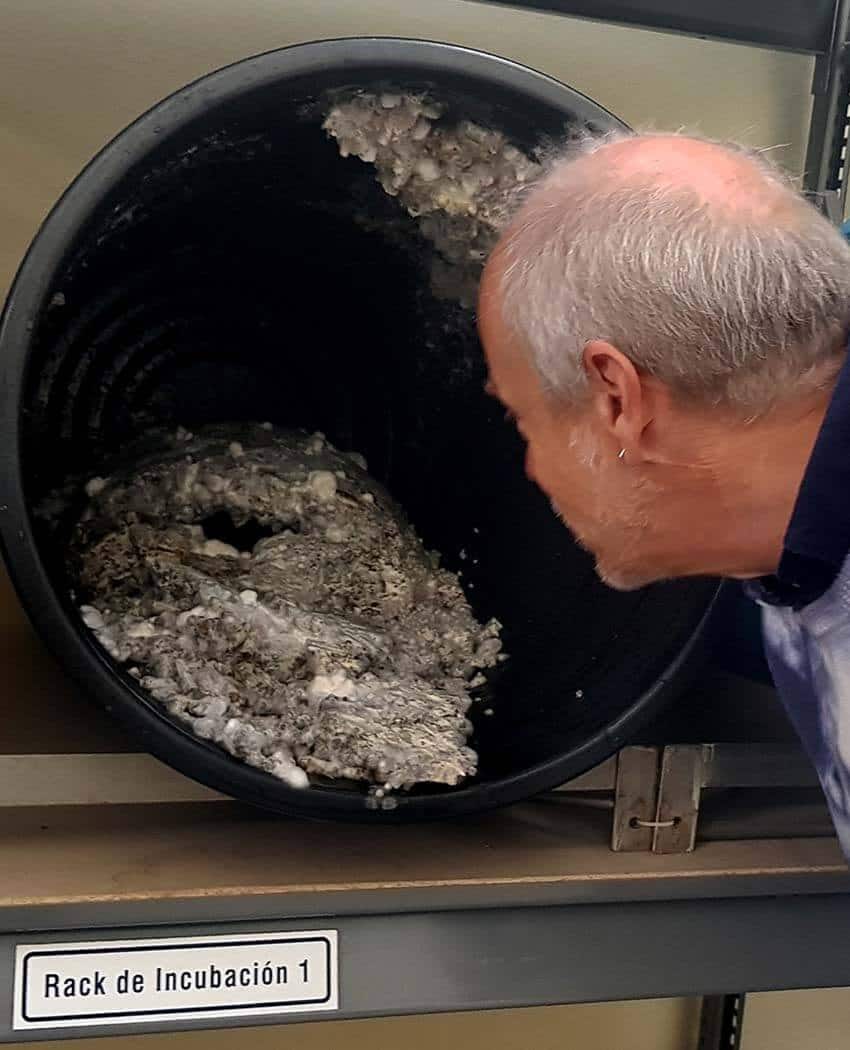

From this small room, we proceeded to the incubation racks where the ground-up mycelium of the oyster fungus is mixed with the cigarette butts.

This mycelium consists of long, fine, white threads like those found under the surface of every forest on Earth, serving as a communication network among the trees. A fungus is really mycelium, and mushrooms are its fruit.

“If we see mushrooms popping up in these containers,” Solís told us, “it means we’ve let the process go on too long.”

Normally, it takes 25 to 30 days for the mighty mycelium to completely wipe out all toxins and degrade the cellulose filters by about 30%.

I was amazed how pleasant a trash can full of detoxified cigarette butts could smell. “Como tierra mojada,” said Solís with a smile. “Like damp soil after a spring rain.”

The now harmless cigarette butts are then dried and next passed through a screen to sift out the cellulose filters that are finally shredded into raw material that can be used as industrial fiber to make concrete stronger or made into paper, notebooks, insulation, flower pots or even earrings.

- To find out more about Eco Filter and becoming one of their cigarette butt recycling ambassadors, visit them on their website Para Bien o Para Mal (For Better or For Worse) or on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.