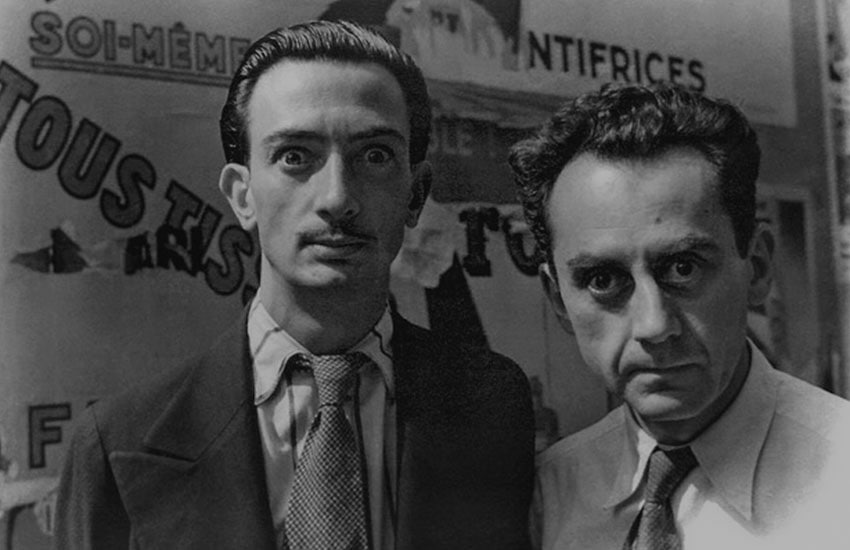

Salvador Dali reputedly remarked to Sigmund Freud, “Edward James is crazier than all the surrealists put together. They pretend, but he is the real thing.”

Perhaps the best proof of James’s insanity is his sculpture gardens tucked away in a rainforest in San Luis Potosí. Officially called Las Pozas, the compound consists of acres of structures with various levels of utility, creativity, termination, and dilapidation, but it’s why people come to the Pueblo Mágico of Xilitla.

The gardens reflect a life looking for purpose.

James was born in 1907 with multiple silver spoons in his mouth, having American industrialists on his father’s side and royalty on his British mother’s. He never had to worry about earning a living or what he spent, but he did worry about being part of Europe’s artistic and intellectual circles.

He began as a patron of ballet, wedding a ballerina. When that marriage ended in a scandalous divorce, James left England for the continent. Here, he became involved with surrealist artists such as René Magritte and Pablo Picasso: James commissioned from Dali — for whom he was a patron from 1936–1939 — wild objects such as a lobster-shaped telephone and a sofa based on the lips of Mae West.

World War II pushed him to the United States, but soon afterward, he went to the then-vibrant expat community in Cuernavaca, Morelos. There he met Plutarco Gastelum, who would be his right-hand man for the rest of his life.

Looking for a place for James’s prized orchid collection, the two came to Xilitla in 1947, finding the pristine Las Pozas, named after its natural pools fed by waterfalls.

James’s orchid sanctuary came to a sudden end when frost killed the entire collection of 29,000 in 1956. But he did not abandon Las Pozas, which he called an Eden. Instead, he turned to building his home and other structures there based on surrealist principles. James sketched out what he wanted built; Gasteum and local craftsmen would make it happen.

Over the next decades, 36 buildings, sculptures and other structures would arise in the rainforest, most near the main waterfall. James gave them poetic names such as the House With a Roof Like a Whale and The House with Three Storeys that Could Be Five.

Artists and celebrities came to enjoy the developing complex’s bathing pools, exotic animals and more. British-Mexican surrealist artist Leonora Carrington painted a mural here, and Mexican artist Pedro Friedeberg designed the pair of hands found at the compound’s entrance. Many of the structures were painted in dreamlike colors, hard to imagine today as almost all of the paint is gone.

By the time he died in 1984 while traveling in Europe, he had spent an estimated US $5 million (roughly $18 million today) on the never-completed project.

Despite Gastelum’s family’s efforts, the compound would be abandoned until the 2000s, as James did not provide for its maintenance after his death. Only a few hardy souls would make the trek to see the ruins, which were quickly succumbing to the climate and vegetation growth.

In 2007, several businessmen and the state government took over the property, investing 600 million pesos to rehabilitate it and make it a protected area. The foundation in charge has done a phenomenal job of promoting it for tourism: thousands have since come to marvel at its structures. Visits are only through tours, which try to keep some control over the crowds constantly stopping to take selfies.

But the compound’s artistic value has been strongly debated.

There was no such thing as surrealist architecture before James came along; the movement was about focusing on what can only be in our minds. James’ devotion to surrealism earns him the moniker of “eccentric” in much literature, but locals in Xilitla bluntly called him a “crazy gringo.”

The structures themselves have invited photography and poetic descriptions, but James himself admitted that the project was “pure megalomania.” His desire was to be seen as something more than a fat checkbook for creatives, but I wonder if he thought he ever really succeeded.

The rainforest itself has assaulted whatever artistic value the structures have. Almost all of the structures are now so dilapidated that tourists are forbidden to enter everything except a small carpenter’s shop. The site was never meant to host large numbers of people, and it is likely that its popularity is making its deterioration happen faster.

Despite my overall reservations, I found a number of interesting photographs to take. Some are due to the curious shapes among the vegetation and waterfalls, others speak more to the idea of imposing human aesthetics on nature.

Efforts to get the site listed with the federal National Institute for Fine Arts (INBA) as an artistic monument have succeeded, but not to make it a World Heritage Site. Xilitla’s economy is now almost entirely dependent on the gardens. The town is filled with small hotels, and a museum dedicated to Leonora Carrington has opened.

Las Pozas is a conflictive curiosity. It is one man’s effort to see himself as an artist — or at least as something more than some crazy rich guy trying to beat boredom. Its decay and envelopment, despite all the work put into patching it up, just may be Mother Nature’s artistic statement about the futility of dominating her in the long run.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.