How would you depict Diego Rivera’s renowned and complex mural The History of Mexico in a space as small as a graphic novel?

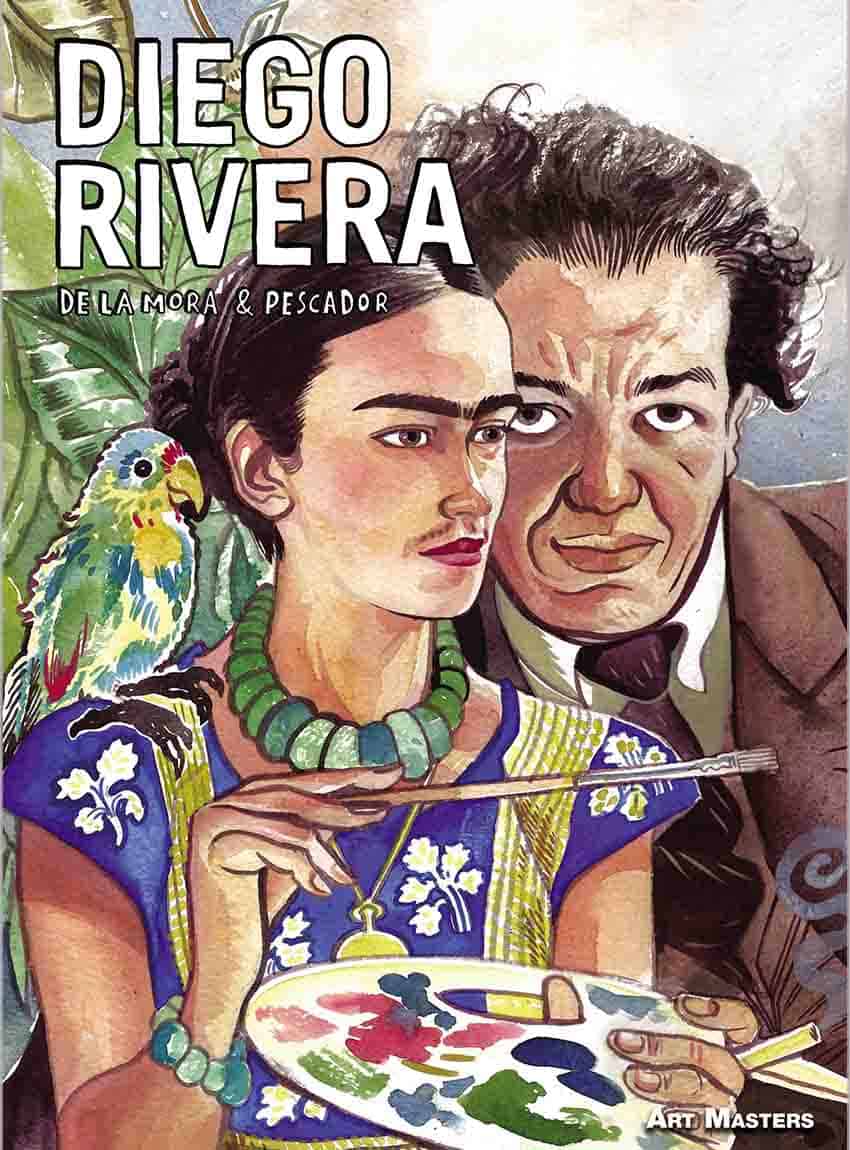

This question challenged the Mexican duo of writer Francisco de la Mora and artist José Luis Pescador as they worked on their biography Diego Rivera, recently published by SelfMadeHero in comic book format.

“[Pescador] recreated the whole thing,” de la Mora marveled in a joint Zoom interview. “You can see the whole mural. He recreated every single element of [it] … It’s [Rivera’s] most important work, in many ways.”

The book is part of a series on art masters, from Rembrandt to Picasso. The latter artist had an important but stormy relationship with Rivera in the early 20th century, reflected in the rainstorm the duo walk through in Paris in one panel.

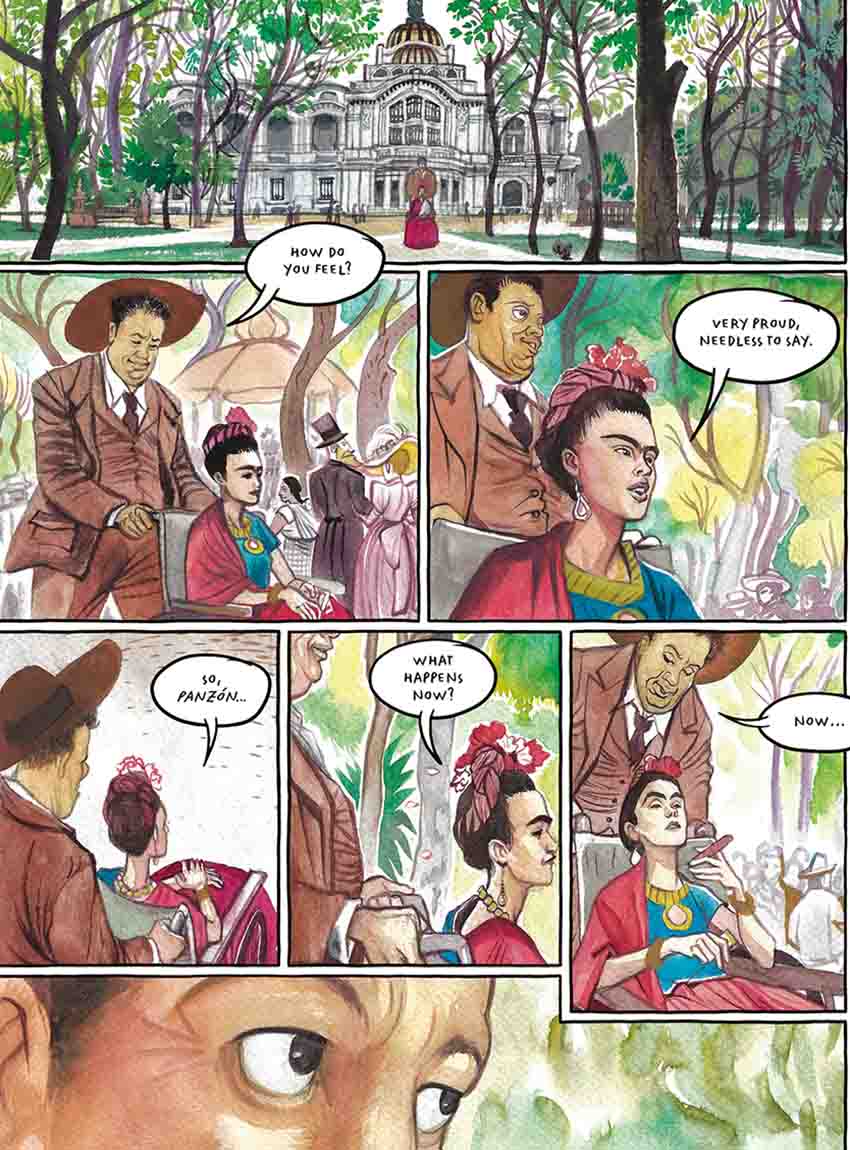

The biggest important but conflicted relationship the Mexican muralist had, however, was, of course, with fellow artist Frida Kahlo, his third and most famous wife. “He fell in love with her,” de la Mora said. “No doubt, the relationship was one of the most amazing relationships in the history of art. Frida was part of Rivera’s life forever.”

To underscore this in the graphic novel, Rivera gives a poignant reflection on their relationship after her death.

“Rivera was creating murals before he met Frida, but I think Frida gave him connections to a different universe, like a shaman — a shaman connecting with forces we don’t understand,” de la Mora said. “I think it’s what she provided for Rivera. In my opinion, it was mutual. Rivera was very important for Frida as well.”

But the book also depicts the playful side of the relationship: he called her the playfully mocking endearment “Friducha,” and she nicknamed him the equally playfully mocking “Panzón” (big belly). The graphic novel also shows the controversial side of Rivera’s life – including his affair with his wife’s sister Cristina Kahlo and, before that, his abandonment of his first wife, Angelina Beloff, after the loss of their baby son in Paris during World War I.

“I don’t think he would have lasted three days in the #MeToo movement,” de la Mora said.

The book does not devote much space to his final marriage to Emma Hurtado.

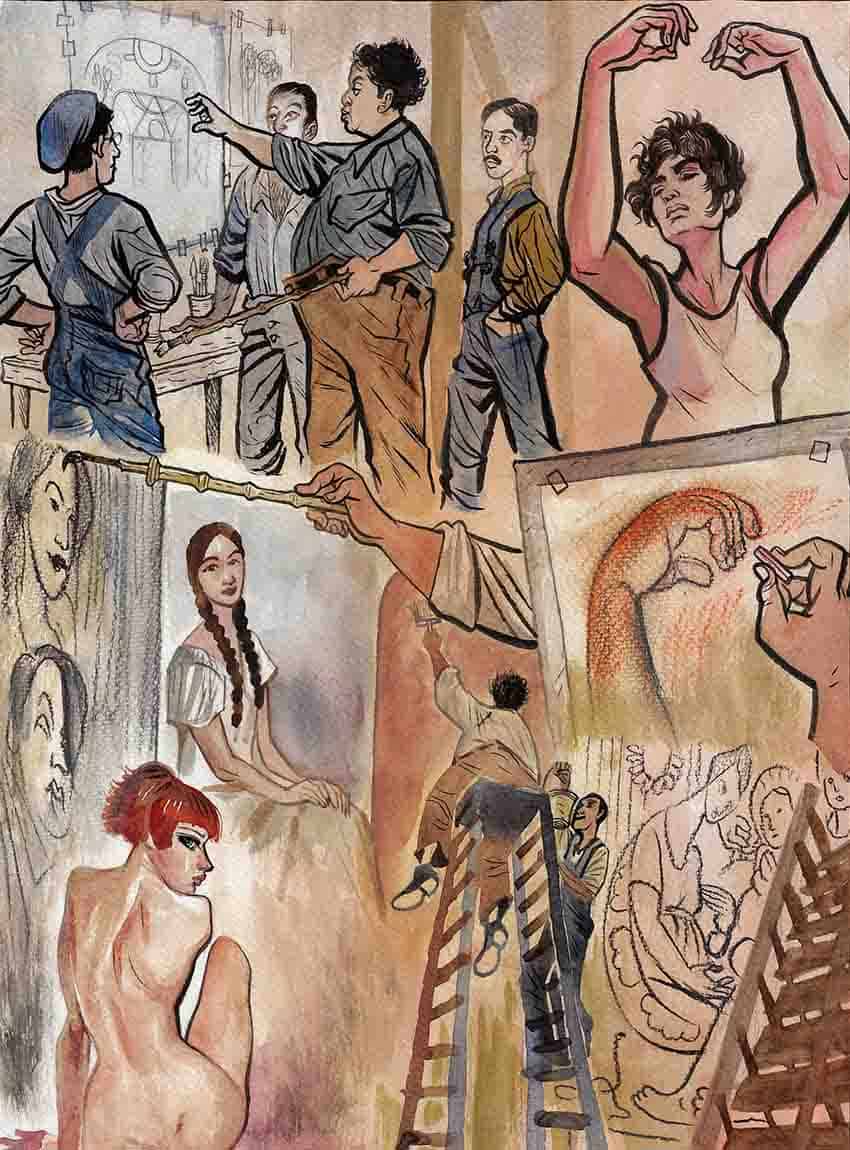

The collaborators sought to paint a balanced portrait of Rivera’s life on a canvas that stretched from Guanajuato to Paris to Mexico City. Throughout, Rivera painted multiple masterpieces while interacting with a collage of great artists and personages of the period – as well as notorious political figures such as Leon Trotsky.

“Trotsky came [to Mexico] as a refugee,” de la Mora said. “[Rivera] embraced him in many ways, helped him come, at a time [when] nobody really offered him a hand.” However, he added, “Rivera always had an agenda. The agenda did not really help him the way he was expecting it to work. He stopped supporting him, abandoned him.”

Whether it was with Trotsky or Trotsky’s nemesis Joseph Stalin or the power couple of Rivera and Kahlo, Pescador said he filled the pages of the graphic novel with “many personalities and characters” over “a big, long period,” spanning a half-century.

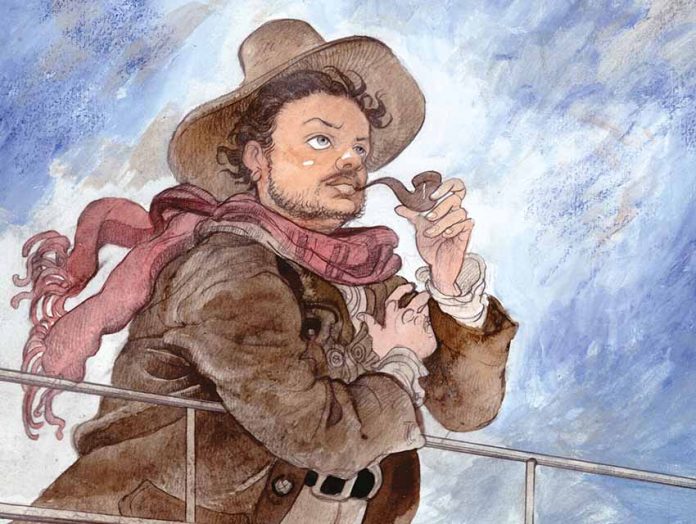

In depicting Rivera himself, Pescador focused on a central feature of the artist’s face.

“The key is the eyes,” he explained. “Like Frida Kahlo said, Diego Rivera has flat eyes. I think this is very important to represent [him]. His eyes are the key.”

Pescador also said, “My goal was to … get inside the mind of Diego Rivera, try to recreate his mind. This is my intent for the color palette.”

He used watercolors throughout. “It reflected, tried to copy, to recreate Diego Rivera’s style of painting,” Pescador said. “This is very important about creating the style to remember the paintings, the murals of Diego Rivera.”

The image of the mural that hangs in the National Palace in Mexico City spans two pages in the book. “It was so difficult because I had to do the correct placement of all the figures of Diego Rivera,” he said. “It took him six years to do this [from 1929 to 1935]. I did this in around 20 days.”

A creatively designed panel in the book depicts the Mexican intelligentsia reflecting on Riviera’s debut mural in 1923 with a diversity of opinions. “[Rivera] was so confident; he was so aware of his own genius,” de la Mora said. “At the same time, he made a lot of enemies in his life.”

This extended abroad: Rivera worked on an ambitious project for Henry Ford’s son Edsel Ford in Detroit, known as the Detroit Industry murals, which raised public outcry, while in the Soviet Union his ideas never even got off the ground.

“He ended up fighting with the people who paid for the murals [in the U.S.]. He was not always very politically intelligent,” de la Mora said. “He ended up being the enemy of all the rich people in the U.S. who commissioned projects … Every genius in the arts has to deal with this kind of thing.”

Asked which Rivera works are their favorites, the collaborators had differing responses: Pescador mentioned the National Palace mural, while de la Mora is fascinated by the Detroit Industry murals, as well as some of his conventional paintings.

The collaborators also explore the extent to which José Guadalupe Posada might have made an impact when Rivera was an up-and-coming artist yet to embark on a decade-long sojourn in Europe. The book envisions a meeting between Posada and Rivera that may or may not have happened, with Pescador emulating Posada’s catrinas.

“He learned from Posada,” de la Mora said. “He visited his studio many, many times. It’s probably true, the influence that Posada had.”

De la Mora asked Pescador to “come up with a couple of pictures of Diego in Posada’s studio, to take Posada’s style, borrow from the period, the idea of Diego to Posada’s eye. Many things in the graphic novel never happened the way Diego put them.”

And yet, the scenes with Posada reflect a larger truth, he said – “how we Mexicans interpret not just art but life and death. It was really important for us to transmit that in the book.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.