The northern border of Guadalajara is formed by the 500-meter-deep Huentitán Canyon, at the bottom of which flows the Santiago River.

In modern days, the canyon is seldom visited except by hardy hikers and athletes looking to test their endurance, but once upon a time the area was of strategic importance for Guadalajara.

The fertile and tropical climate at the base of the canyon provided the perfect environment for orchards, while to the north lay undeveloped areas upon which the citizens of Guadalajara almost entirely depended for firewood.

The important role the canyon played in Guadalajara’s development was brought to my attention recently when members of an organization called Jalisco Desconocido made a surprising discovery in the bush far below the level of the city streets.

“We found it!” announced Luis Abarca, the group’s leader. “We located the legendary hacienda which once managed Paso de Ibarra, named after Spanish conquistador Miguel de Ibarra and one of the major crossing points of the Santiago River.”

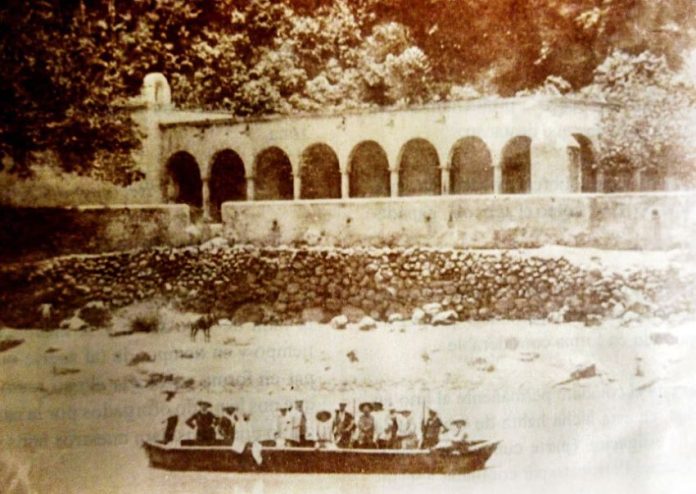

Hacienda de Ibarra was a working estate, supplying mangos, papayas, sugar cane and oranges to Guadalajara, not to mention its curious caracolillo (peaberry) coffee beans.

“We were truly amazed to see that the old hacienda, built in 1820, is still standing and still beautiful even though it is now enshrouded in vines and creepers,” said Abarca.

Jalisco Desconocido is a group of six persons who enjoy hunting for old trails and forgotten historical monuments.

“We’ve been exploring Huentitán Canyon for eight years,” Abarca told me. “In the process, we’ve come upon the ruins of quite a few historical sites, such as the hacienda of Don Marcelo Alatorre, La Casa Colorada and the remains of several military camps, but during all this time, we had no idea that this Hacienda de Ibarra was down there.”

While viewing the barranca using Google Maps, the group glimpsed what looked like a building alongside the river. Abarca and José Francisco Posadas then decided to hike to the bottom of the canyon and hunt for the old hacienda but found no trail of any sort as they made their way downriver.

“We needed machetes to chop our way through jungle, thorns, cacti and other kinds of maleza [weeds],” said Abarca.

When they finally got to the spot they were looking for, sure enough, there was an old hacienda there.

“That first visit to Hacienda de Ibarra was really heavy and took nine hours, including the 500-meter climb back up to the top,” Abarca says.

To understand what the explorers found, it is necessary to go back to the early 1800s, when the city had expanded as far north as possible, right up to the edge of the huge geological fault that separates the states of Jalisco and Zacatecas.

The people on both sides needed a way to get goods across this formidable obstacle.

“There were several points where they could cross the river, such as the Hacienda Del Jabali, Puente Grande and this Hacienda de Ibarra,” Abarca said. “The Puente Grande route was much longer, so they preferred Jabali and Ibarra.

Hacienda del Jabali charged a lot more money than Hacienda de Ibarra, but they offered security.

“They would provide armed guards who would accompany parties from the north all the way to Guadalajara,” Abarca explains.

Hacienda de Ibarra, on the other hand, was much cheaper.

“The owner had boats to ferry your merchandise across the river, but once you had disembarked it was your problem to get the goods to Guadalajara,” Abarca says.

According to researcher Jorge Robles, crossing the Paso de Ibarra in the 1800s was anything but an easy task. People, goods, animals and even stagecoaches had to be ferried to the other side.

“To achieve this,” writes Robles, “a thick rope made of maguey fibers was stretched across the river. The boatmen would then grab onto it and, using pure muscle power, would literally haul their panga [boat] or raft from one side to the other.”

This risky procedure could only be done under ideal conditions. When the river was rough or too high, service could be suspended for days.

“Once you got across Paso de Ibarra,” Abarca says, “you would have to follow the river for several kilometers and then haul your goods up a steep trail to the city. All along the way, it is said, there would be brigands lying in wait for you.”

These bandits were so bold as to threaten the life of the hacienda owner’s children. As a result, the family abandoned their home, leaving someone to look after it.

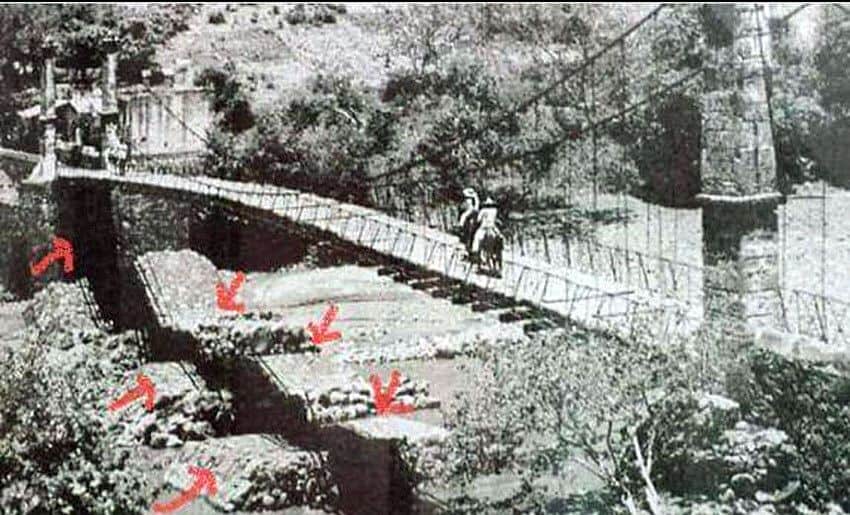

Meanwhile, the Alatorre family, who had a hacienda on the other side of the river, decided at some point to construct the first bridge over the Santiago River, which would make this whole transportation process far easier, says Abarca.

However, once they finished, they soon ran into a problem.

“With great difficulty, and at great cost, they succeeded in building the bridge, but the very next time the river flooded, the whole thing was totally destroyed,” he said.

It must have been evident to the Alatorres that they needed another, totally different, type of bridge. Fortunately for them, the newspapers of the day were touting the inauguration, in 1883, of the Brooklyn Bridge in New York, at that time the longest suspension bridge in the world.

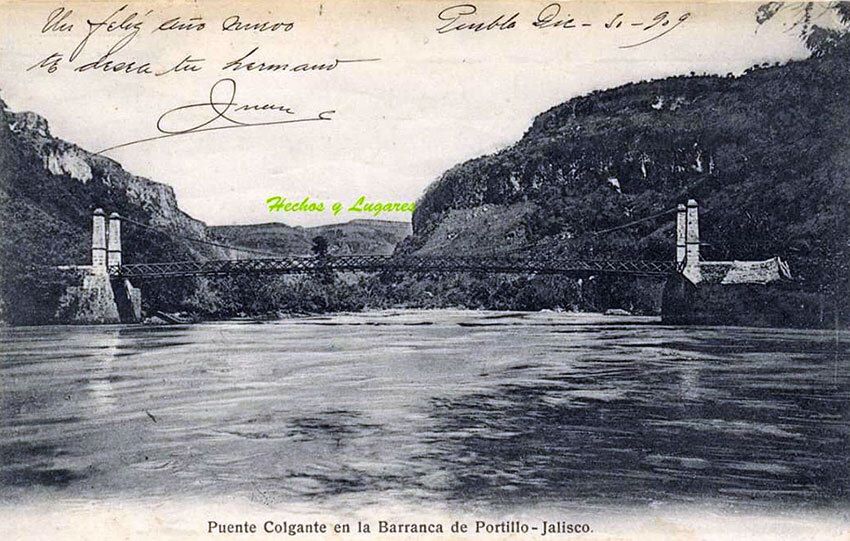

This was exactly the design the Alatorres were looking for, and in 1894 the Puente de Arcediano was built at Paso de Ibarra by engineer Salvador Collado.

This, it is claimed, was the third suspension bridge built on the American continent.

It served its purpose well, resisting the vicissitudes of climate and the ravages of the Santiago River right up until 2005, when it was dismantled and rebuilt further downstream in anticipation of a dam project that never happened.

“The Puente de Arcediano lasted 111 years, but such was not the fate of Don Marcelo Alatorre’s hacienda,” says Abarca. “All that’s left of it today is one arch which, I’m sorry to say, is being ‘eaten’ by tree roots and will soon be no more.”

How the Hacienda de Ibarra’s ruins managed to fare so much better, I don’t know, but if you’d like to have a peek at it — without hiking down and back up the Huentitán Canyon — take a look at Jalisco Desconocido’s five-minute video Ex-Hacienda de Ibarra, Barranca de Huentitán, Jalisco Mexico. My congratulations to little groups like Jalisco Desconocido, who seek out and explore vestiges of Mexico’s colorful history, and are willing to share them with us.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years, and is the author of “A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area” and co-author of “Outdoors in Western Mexico.” More of his writing can be found on his website.