Hidden away in rural Mexico are majestic waterfalls, meandering rivers and sparkling lakes. These are the pride of local people and their favorite places to go for a carne asada on a Sunday afternoon.

Unfortunately, the water in many of these streams and lagoons is contaminated, and every rancher or campesino (farmer) picnicking nearby laments the fact that they are being polluted by aguas negras (blackwater) pouring into them from the nearest town.

When you suggest they build a sewage treatment plant, they almost always give you the same reply:

“We already have a planta de tratamiento, sí señor! The government built one for us 10 years ago, but, sad to say, it’s no longer in operation. The building is over there at the edge of town, locked up and abandoned.”

Building a plant, I learned, is one thing. Maintaining it is quite another. A small community cannot afford the high operating costs, and even less the salary of an expert to run the place.

Having heard this same story again and again, I was all ears when a biologist at the Autonomous University of Guadalajara mentioned to me that techniques exist for processing human waste using ponds and flowers with no need for chemicals or expensive machinery.

“There is,” professor José Luis Zavala said, “a low-tech solution to the aguas negras problem, and country people can maintain these sewage treatment sites all on their own.”

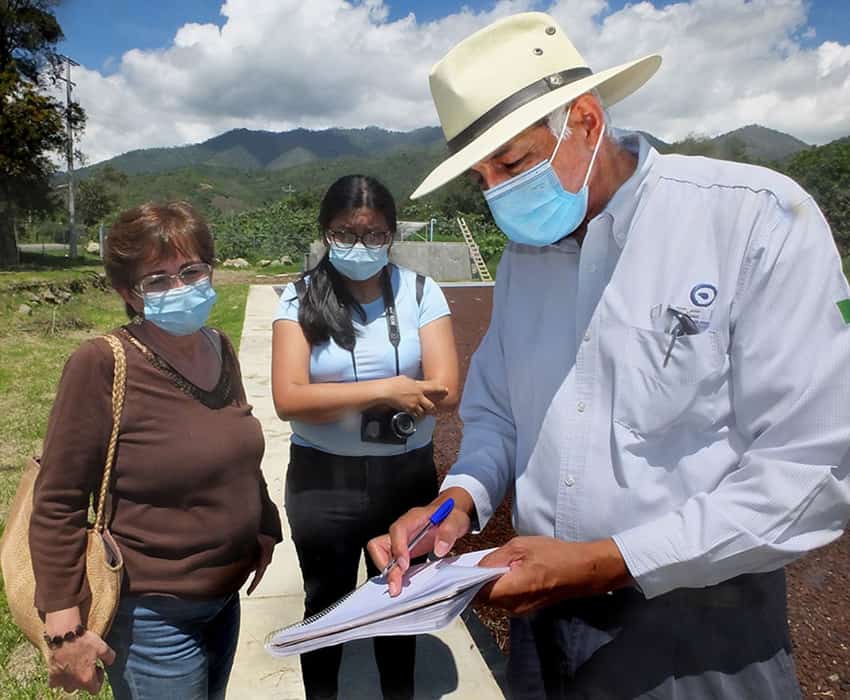

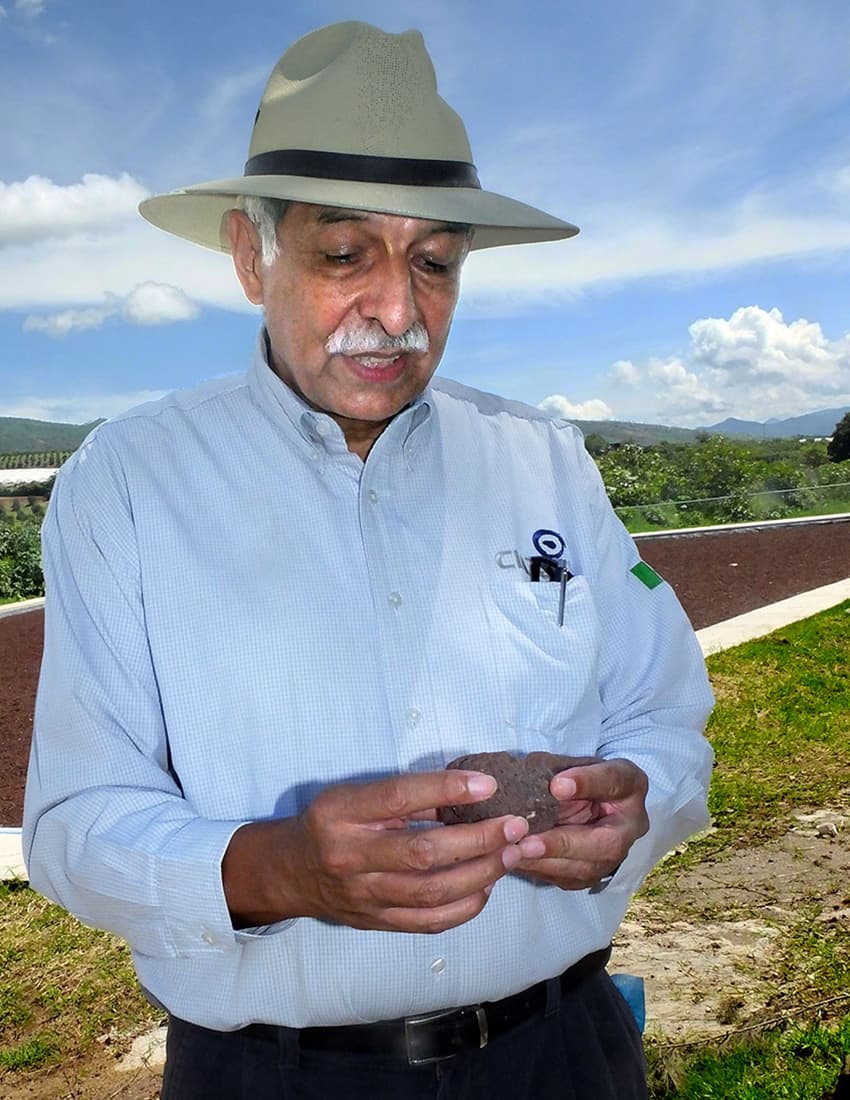

A few weeks later, I was introduced to Dr. José de Anda of Jalisco’s Environmental Technology Research Center. He and the now-deceased Dr. Alberto López-López developed a passive system for treating raw sewage using a constructed wetland that they demonstrated in 2018 was able to reduce organic contaminants and coliform counts to well within national environmental standards.

De Anda took me to the small town of Atequizayán, Jalisco, located near Ciudad Guzmán, 100 kilometers south of Guadalajara.

“With the cooperation of the local people, we have built a demonstration wastewater processing system using what is called a constructed wetland,” said de Anda.

Before arriving at Atequizayán, I had imagined the wetland I was about to visit would be some kind of swamp spread over many kilometers.

To my surprise, I saw that the demonstration treatment plant consisted of a small building next to what looked like a clay tennis court minus the net.

“Where’s the water?” I asked de Anda.

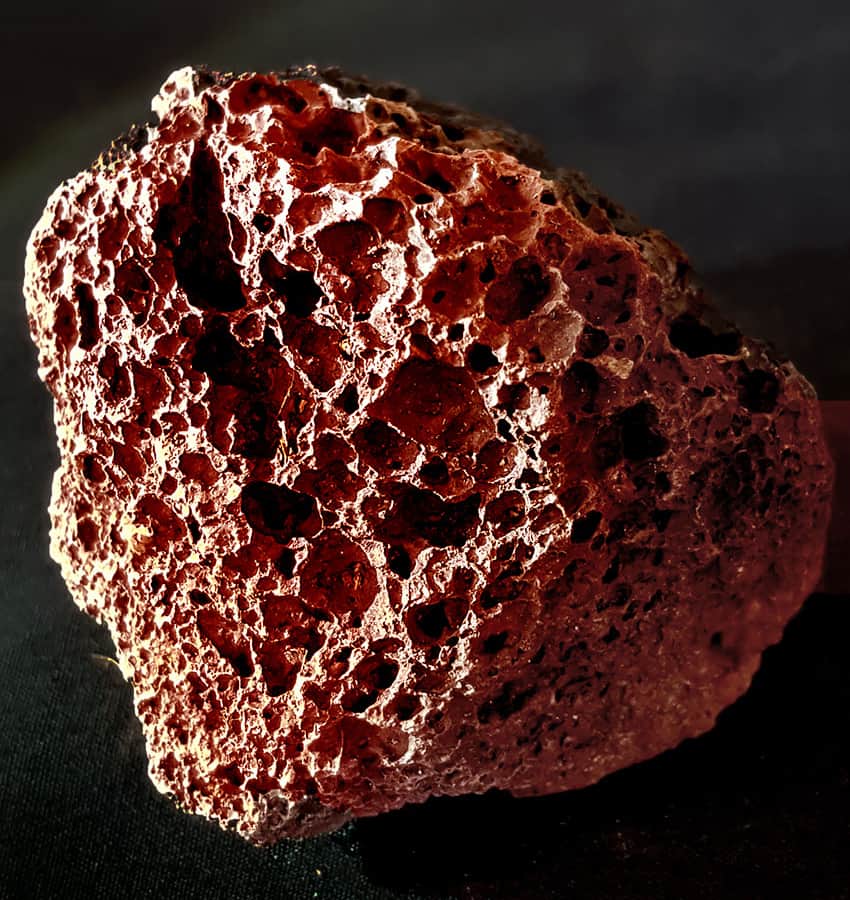

“Under what you are calling a tennis court,” he replied. “But the red surface you’re looking at isn’t clay, it’s a bed of small volcanic rocks, which go by the name of tezontle.”

Tezontle is a Mexican word for cinder-like volcanic rock filled with countless little holes, originally formed by gas bubbles. Tezontle (scoria to geologists) is available from Jalisco to Veracruz, and it’s just about the cheapest rock you can find in Mexico, widely used for road construction.

“You mean this little building plus a swimming pool full of cinders is capable of processing the sewage created by 800 people?”

“Yes,” replied de Anda. “Before we set up this demonstration plant, Atequizayán had no wastewater treatment system of any kind. All their raw sewage went down a canal that, unfortunately, took it straight into La Laguna de Zapotlán.”

“What’s special about this approach to treating sewage,” he continued, “is that it doesn’t use energy. We call this a nature-based solution, and we have been working on it for 10 years. It’s a combination of anaerobic processes and a wetland.

“It’s not quite complete, as we set it up only seven months ago and we still need to plant flowers in the wetland, which will absorb the excessive nutrients still present in the treated water, but the system you see right here is already successfully removing most of the carbon compounds contaminating the water.”

De Anda took me on a tour of the facility. We began at one end of the building, where a mixture of sewage and drainage from the town flow through metal grates, which catch rocks, into a sump that traps sand. The raw sewage is then pumped into a septic tank, and from there into a very curious upflow anaerobic filter, or biodigester, which is nothing more than a big container filled with tezontle.

Here, something amazing happens. The fecal matter in the wastewater is removed, using a completely natural system.

“Tezontle stone,” explains de Anda, “is very special. It has a vast amount of surface area both inside and outside because it is full of holes. Every cubic meter of tezontle represents close to 300 meters of active surface. And this surface area happens to be the habitat of a lot of bacteria that work in favor of decomposing the contaminants that are in the wastewater.

“So these beneficial bacteria literally catch the contaminants and use them to grow on. Apart from this, tezontle also has the ability to absorb some metals and contaminants. So this volcanic rock is truly extraordinary.”

“How frequently do you have to change the tezontle?” I asked him.

“Oh, it keeps on working for years. Once you have things set up, you can rest assured that these scoria rocks will give you service for at least 30 years without the use of any energy to treat the wastewater.”

The biodigester is the place where all this takes place, de Anda told me. Here, the very bacteria that we have in our own digestive system go to work. While the wastewater passes through the biodigester, 70% to 80% of its contaminants will be transformed into environmentally friendly compounds.

“Next,” continued the researcher, “to bring these partially processed aguas negras up to Mexican national standards for purified wastewater, we need a constructed wetland.”

To me, this “constructed wetland” looked very much like an Olympic-size swimming pool, but only 70 centimeters deep and completely filled with volcanic rocks about the size of lemons. It also contains water flowing from the biodigester, of course, but this reaches a maximum height of only 60 centimeters, meaning the carpet of rocks is dry on the surface and you can walk on it without sinking in.

The purification process is completed as the water moves through the rocks, “simply with the help of bacteria found in the environment,” says de Anda.

Here, the water will be oxygenated by plants.

“We could use reeds or cattails,” he says, “but we prefer to use ornamental plants like Agapanthus africanus (African lily), Canna indica (Indian shot) or Clivia miniata (natal lily), which have both an aesthetic and a market value.”

A clever gardener, of course, could create a beautiful design here by mixing flowers and colors.

The oxygenated water that flows out of the wetland is crystal clear, smells of tierra mojada (wet earth) and could be used to raise fish or to water corn, sorghum or avocado trees, for example.

The cost of building this facility was about 3 million pesos, an amount similar to the cost of a traditional treatment plant.

“But,” says de Anda, “once you have it, the operating and energy costs are negligible, and you don’t need to hire a rocket scientist to run it.”

Hopefully, in the coming years, Mexicans will begin to see less water pollution and more Agapanthus across their beautiful country.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.